People

‘Everyone Is in a State of Panic Right Now’: 7 Mid-Career Artists on How They Are Facing the Enormous Challenges of the Coronavirus Pandemic

Kader Attia, Kathe Burkhart, and others on how they have rearranged their lives in recent weeks.

Kader Attia, Kathe Burkhart, and others on how they have rearranged their lives in recent weeks.

Naomi Rea

Nationwide lockdowns, closures of non-essential businesses, disruptions to supply chains: the impact of the coronavirus can be felt everywhere.

The art world is no different.

Cancelled exhibitions mean lost income for artists, while studio shutdowns leave assistants wondering when they will get their next paycheck. The obstacles seem endless.

To get a sense of the landscape, we asked seven artists how the crisis has affected them and what they expect its long-term consequences to be.

Janaina Tschäpe at work in her home studio in April 2020. Photo courtesy the artist.

At the beginning of March, when a lot of galleries, collectors, and friends were in New York for the Armory Show, we were still going to openings, dinners, and visiting the fairs. Late Sunday, I remember my daughter saying there were something like 150 cases in New York State by that time. The next day, I drove her to and from school because I didn’t want her to take the subway. By Wednesday morning, we came to the decision that my studio assistants should start to work from home and I made the decision to go to Brazil with my daughter before her school closed.

I am lucky to have a farmhouse in the mountains. We are pretty much self-sustainable here, and my daughter can attend school online and I have a studio where I can work.

It was a little traumatic, actually, when we first got to the farm. I didn’t realize how much anxiety I would cause the locals due to the fact that I was coming from New York. An audio recording started circulating on social media spreading fake news that my daughter and I were sick and were the first cases of the virus in the countryside. It was quite painful because as you can imagine, I started getting phone calls from everyone and even had an ambulance show up to the farm. I couldn’t install my internet or get gas or basic supplies because people were too scared to come near us. I finally sent around a video stating that we weren’t sick and just quarantining in our house.

Everyone is in a state of panic right now, with the closing of borders, people succumbing to racist sentiments, and fear driving people towards horrible actions. It is so worrisome that both Brazil and the US are stuck with ignorant leaders who continue to guide us in the wrong direction, concerned only about the economy and not about people. This situation is revealing a lot of our mistakes, and that we are putting a little too much money and attention in the wrong places.

I have now started a project to produce 2,000 masks for the community here. The nearby town is completely unprepared to deal with the virus, there is no infrastructure and no support. We’re trying to get someone from health services to go around the community and provide information to elderly people who are at greater risk of complications. We have already bought the fabric for the masks and recruited the help of local women to sew them. Hopefully, our efforts will make the town a little more prepared if the virus does spread to the countryside.

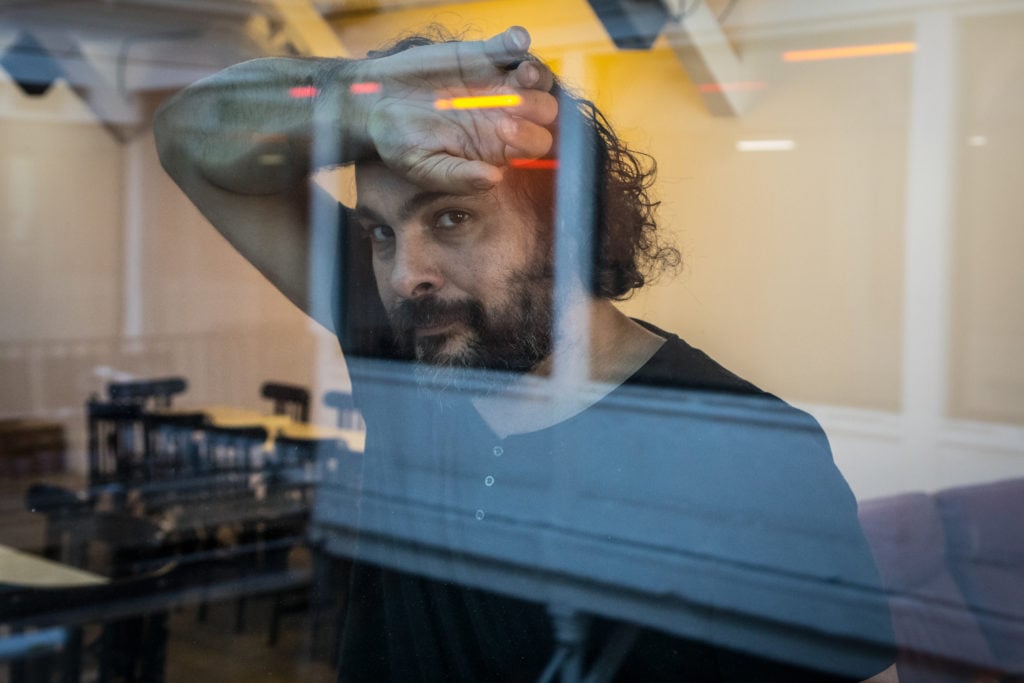

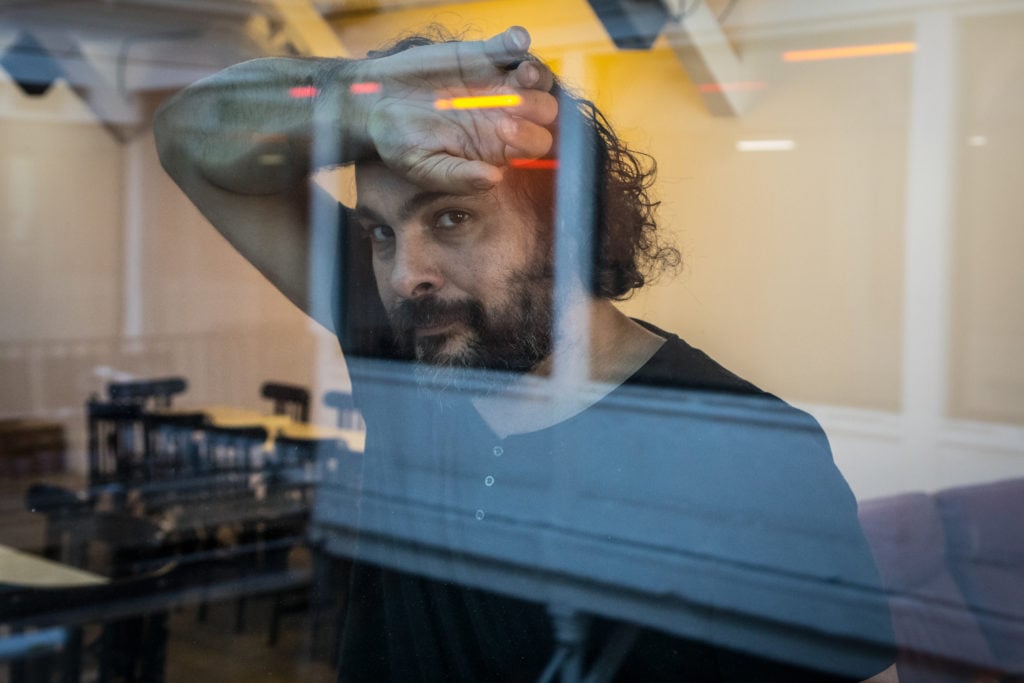

Kader Attia. Photo by Camille Millerand.

In mid-February, I was in Lebanon for a workshop, and there, people were already talking about the virus and wearing masks in the street. That’s when I discovered that there was actually a coronavirus epidemic. When I came back to Europe at the end of February, I was very surprised to see that people were not taking this seriously.

In addition to my artistic practice, I run a space for debates and exchanges in Paris named La Colonie. On March 15, the French government ordered all cafés and restaurants to close. We have been happy to do our part to flatten the curve and help reduce the virus’s spread, but this also hits us very hard. The space is totally self-funded, so being closed is a financial disaster for us, and we don’t know if we will be able to come back from that.

Like everybody now, I am quarantining. I am using this time to read and try to reflect on and make sense of what is happening. There were inequalities and injustices before this pandemic, and with the economic crisis that will follow, they will only get wider and deeper. We need to invent new ways to deal with our environment, but also to anticipate the social and economical disaster that has already started. I am thinking about the acceleration of forms of racism that already existed before the pandemic, like the rise of fascism all over Europe and North and South America. There is a high risk that many countries could be seduced by the nationalist sentiment that this virus and the narrative surrounding it exacerbates.

There is a lurking neo-nationalism that is emphasized by this virus. Despite the French government’s efforts, both extremist left-wing and right-wing nationalist parties can criticize the French healthcare system for becoming neo-liberal, because hospitals are being treated more and more like companies and asked to generate profit. They could push the idea that the healthcare system needs to be nationalized, like other essential activities.

The problem with these kind of ideas is that, even if there is some truth to them, they are very dangerous because they can be the ground for helping nationalist ideologies to come to power. And we all know that nationalist ideologies are fueled by racism, exclusion of the other, isolationism, authoritarian policies, and so on. We need to be careful with this. I speak about France because it is the country I know best, but other countries can be tempted by this too.

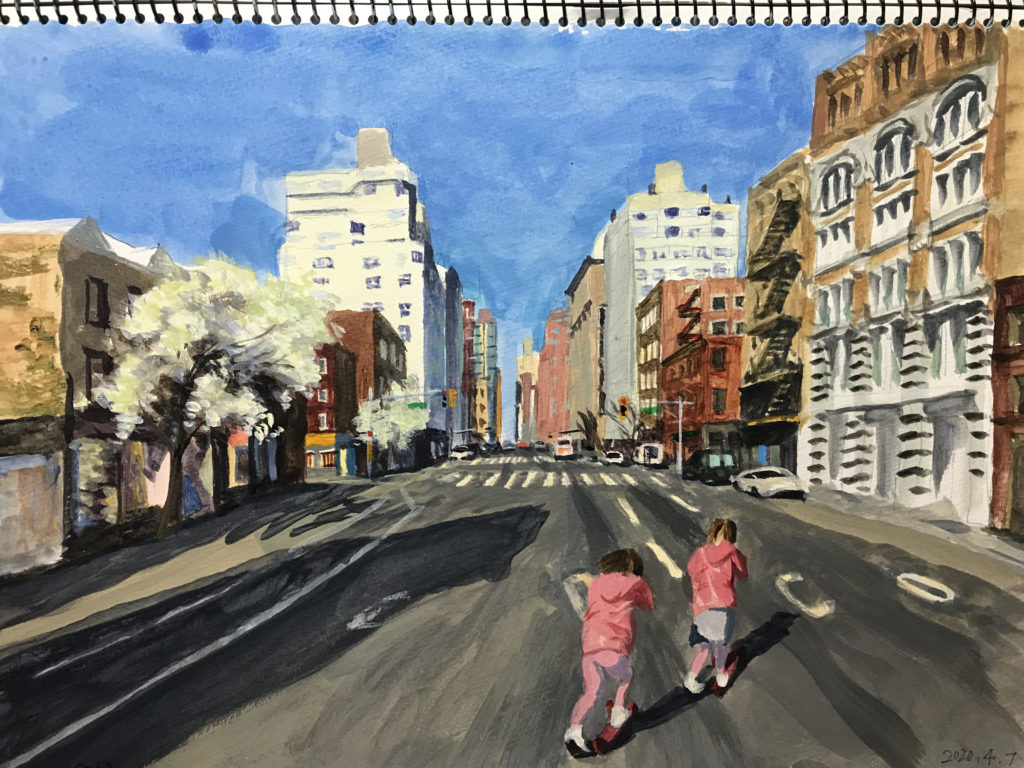

©Liu Xiaodong Studio.

At the end of January, I went to Eagle Pass, Texas, to paint, and since the opening of my show at Dallas Contemporary was scheduled for April 14, I came to New York to wait for the opening. As of today, I haven’t been able to return to my home in China. My shows—”Borders” at Dallas Contemporary and “Uummannaq” at the Faurschou Foundation in New York—have both been cancelled. Having shows cancelled is not a big deal, we all had to quit what we were doing and wait. Fortunately, these shows will be rescheduled for after the pandemic, hopefully in autumn.

Now, I’m in my New York apartment where I spend time cooking and doing watercolors of the streets. In the long-term, learning to slow down my life’s pace will be a good thing—to reduce what is unnecessary, to live a simpler life.

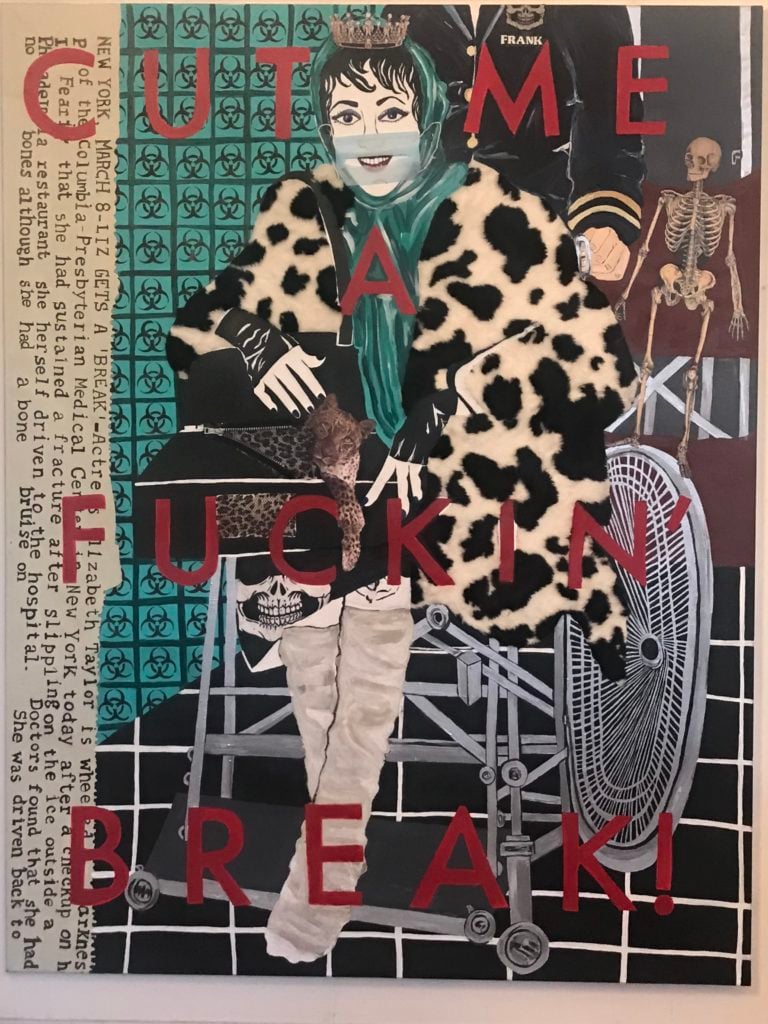

A newly completed work by Kathe Burkhart. Photo courtesy the artist.

My generation has already been through the AIDS and Hepatitis C epidemics. Here we go again—except that now the whole world has to live the way we did, with so much fear and loss.

I work between Amsterdam and New York, and was due to fly back to New York this week. Now I’m stuck in place for an indeterminate time. The international borders are closed. I worry about my friends in the States, especially in New York. Someone dear to me has been sick.

I had a solo show that was scheduled to open at Fredericks & Freiser on April 30. It has been postponed to the fall. If there is a fall. This means loss of sales and income, loss of visibility, disappointment, life and work on hold.

We are on an “intelligent lockdown” here, so I am social distancing and staying at home mostly, since I have some autoimmune issues and have to be very careful. I go to my studio, which is a 10-minute walk away, but less frequently. I’m still working, and reading and writing, when I’m able to concentrate.

The long-term impact of the crisis remains to be seen. My transatlantic lifestyle may become impossible if it’s not safe to fly. I really don’t want to risk it until there’s a vaccine or a medicine that works, but I may have to. I may have to lose a country. It’s bad here, but it’s worse there. For those of us who can survive, the aftermath could radically restructure New York. In recent years, the city has become unsustainable for artists to work in. So maybe there’s a potential for radical positive change. But a best-case scenario could be a long way off.

Patricia Cronin. Photo by Grace Roselli for Pandora’s BoxX Project.

A major national museum cancelled a large commission [of mine]. I don’t think most salaried curators understand artists are actually small businesses with substantial financial responsibilities. I think artists are the most optimistic people. We rent commercial real estate, pay commercial real estate taxes, pay for insurance, electricity, and heat before we buy one brush, tube of paint, or block of clay. And then most of us work alone day after day, year after year, decade after decade, on something we believe is important, serious, hoping someday someone will trade us money for some of that work. If that isn’t optimism, I don’t know what is.

I’m obligated to pay the studio rent, [but] even if I was eligible for the [US government’s] Small Business Administration money, it would have been tiny, and would go straight to the landlord and cover less than 3 months. Artists are pretty much on their own. Art supply stores and foundries are closed now, so I’ll use materials I already have. It might not be the best business model, but it’s a meaningful way to spend a life.

Sophie Whettnall at work. Image courtesy the artist.

The crisis hit me when I realized I had to stay confined at home and face the reality of having two wild kids 24 hours a day. So I went directly to my studio and brought back home a kind of survival kit to be able to work from here. Right now, I am getting back to work with a simple notebook, or just paper, scissors, and a pencil. When I start a new work, I find these are the best tools for me to put down my thoughts. Luckily, I am just coming out of two very intense years of exhibitions and books. The beginning of this year was dedicated to an intense studio practice, so I am continuing to do that, but on a smaller scale.

Until now, none of my projects have been cancelled but everything has been postponed. I have a lot of public projects for Belgium and France, and let’s hope they will [still happen].

My days are sober and quite well-organized. I do homework in the morning with kids, and in the afternoon and evening, I work for myself. I must say, I deeply enjoy this very simple life: no rush, no stress, no hurry. But there is of course a big “but.” What are we going to become after this big pause? How will the world recover from this crisis? What will the world be like?

All this is constantly in my head and I am sure it will transfer into my work. We have always managed to overcome wars, crises, and drama. Let’s hope we will make something constructive out of it for the planet. Of course, art has an important role in this, as it has always had.

Ann Craven in Cushing Maine studio. Photo courtesy the artist.

My main concern right away is my studio assistants and how to make things work with quarantine. So I am trying to get grants and loans that are being offered to small businesses and trying to keep it going for them. They need to work and pay rent and live life, we all do, so I’m trying my hardest.

Some group shows [that I’m in] have been cancelled, but I’m working on shows for the end of this year that are staying put. I am working on a US Embassy Project of Sri Lanka birds that is helping to keep my creative spirit in gear. The birds in Sri Lanka are unreal, gorgeous, and thriving, and nature always wins, you know. So for me to be painting these magnificent birds right now is really an incredibly uplifting experience.

I am in close touch with a local Sri Lankan bird photographer who takes photos of the local birds in his spare time. There is a huge lockdown in that country, so this gives the photographer an excuse to get out and shoot more photos when he is allowed.