People

Artist Margaret Keane, Whose Husband Tried to Take Credit for Her Paintings of Big-Eyed Characters, Has Died at 94

Keane was the subject of a 2014 biopic directed by Tim Burton.

Keane was the subject of a 2014 biopic directed by Tim Burton.

Vittoria Benzine

American artist Margaret Keane, whose six-decade painting career was occluded for years by her husband, who claimed to have made the works himself, died on Sunday, June 26, in her Napa Valley home at the age of 94. The cause was heart failure.

Born Peggy Doris Hawkins, the Nashville-raised painter gained fame the world over for her signature style “Big Eyed Waif” (or simply “Big Eyes”) paintings. The saucer-shaped gazes of her characters reportedly stemmed from the artist’s childhood hearing problems, which forced her to seek cues from faces.

Keane started painting big-eyed angels as a child at her family’s Methodist church. She was enrolled in art classes at the Watkins Institute by age 10 and attended the Traphagen School of Fashion in New York City at 18.

Yet she wouldn’t gain acclaim for her art until years after her second husband, Walter Keane, shot to primetime television fame peddling her paintings as his own.

Margaret Keane, Pocket Poodles. Courtesy of the LA Art Show.

The couple lived in North Beach, San Francisco during the 1950s and 1960s, when she signed her paintings with their shared last name. Walter’s manipulations marred Keane’s first attempt at an authentic painting career: at the height of his false fame, her real works resonated all over America. Patrons included Natalie Wood and the Kennedys.

Interest in Keane’s work surged in 2014 when admirer and filmmaker Tim Burton made her life story into a live-action film, titled Big Eyes, starring Amy Adams. The film helped raise her legacy to cinematic proportions.

Though lovely photos from the afternoon Keane spent teaching Adams to paint suggested a sweet narrative, the effectiveness of Burton’s film was reflected in the artist’s difficult watching it.

“It was a very emotional, traumatic experience when I first saw the movie,” Keane said at an early screening, according to the Hollywood Reporter.

In 1964, Walter submitted Keane’s painting of a sweeping staircase packed with waifs for the New York World’s Fair. Chosen as the focal point for the Pavilion of Education, the work was blasted by a New York Times critic, after which the selection was withdrawn on the grounds of “bad taste and low standards.” (Andy Warhol remarked, “I think what Keane has done is terrific! If it were bad, so many people wouldn’t like it.”)

But Keane’s creative vision didn’t go down that easily. In 1965, she divorced Walter and commandeered her own story, challenging him to a paint off in 1970 to prove herself once and for all.

He couldn’t bring himself to participate, complaining of a sore shoulder. Keane painted her piece anyway, and emerged the de facto winner. She finally got closure in 1986, when a judge ordered them both to paint in the courtroom.

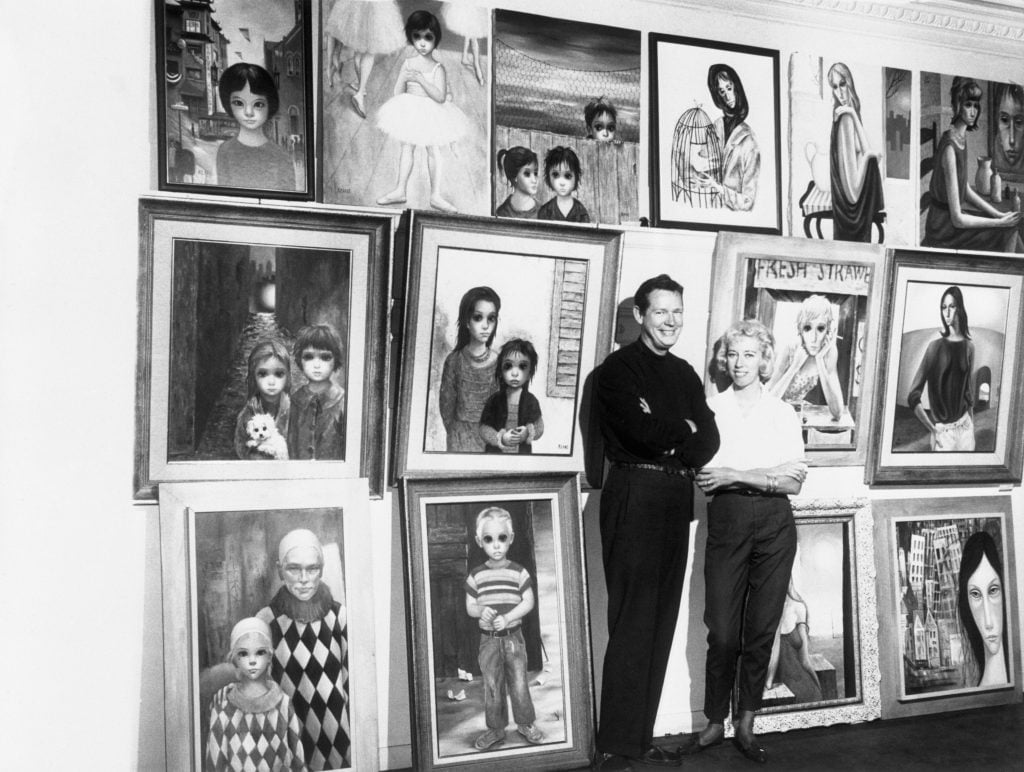

Walter and Margaret appear together in a photo from 1960.

Throughout her life, Keane’s portraits of women and animals bore the edge of Surrealism. Big eyes united every work, whether it depicted mothers, puppies, or scintillating young women. She willfully synthesized her female perspective with the male gaze: Keane’s official biography names Amedeo Modigliani as a foremost inspiration, alongside Van Gogh, Henri Rousseau, Leonardo da Vinci, Gustav Klimt, Edgar Degas, Picasso, Sandro Botticelli, and Paul Gauguin.

The bio also cites Keane herself as an inspiration for cultural phenomena like the Powerpuff Girls.

Keane maintained Keane Eyes Gallery in San Francisco and kept painting every day into her last years. After Burton’s film introduced a new generation to her work, Adams won a Golden Globe, Christoph Waltz was nominated for Best Actor for playing Walter, and the film’s title track by Lana Del Rey was nominated for Best Original Song. Keane herself received a lifetime achievement award in 2018 at the Los Angeles Art Show.

She is survived by her daughter, Jane Swihert; five stepchildren from her third marriage to Dan McGuire; and eight step-grandchildren.