Art World

Beyoncé Has Been Masterfully Remixing Art History for Years. Here Are Some of Her Greatest References, Decoded

From the Italian Renaissance to Afro-Futurism, Beyoncé has taken elements from it all to create her own visual language.

From the Italian Renaissance to Afro-Futurism, Beyoncé has taken elements from it all to create her own visual language.

Maria Brito

She is crouching, surrounded by poppies, peonies, orchids, and roses in white, pink, burgundy, and yellow. She’s staring straight at the camera, not a hint of shyness in her gaze. She is semi-naked, protected by a veil, a belly notably protruding. It’s February 1, 2017, and Beyoncé Knowles-Carter has just announced to the world via her own Instagram account that she is pregnant with twins.

The image is highly artistic and enticing; we can’t take our eyes off everything that is in it. A few hours later, other photographs from the same series start showing up on her website and then migrate across the internet. We learn that Los Angeles-based, Ethiopian-born artist Awol Erizku has created this portfolio to celebrate and commemorate the announcement. The series is titled “I Have Three Hearts”—inspired by an accompanying poem by Somali-born, London-based Warsan Shire, who also collaborated on the lyrics for Lemonade.

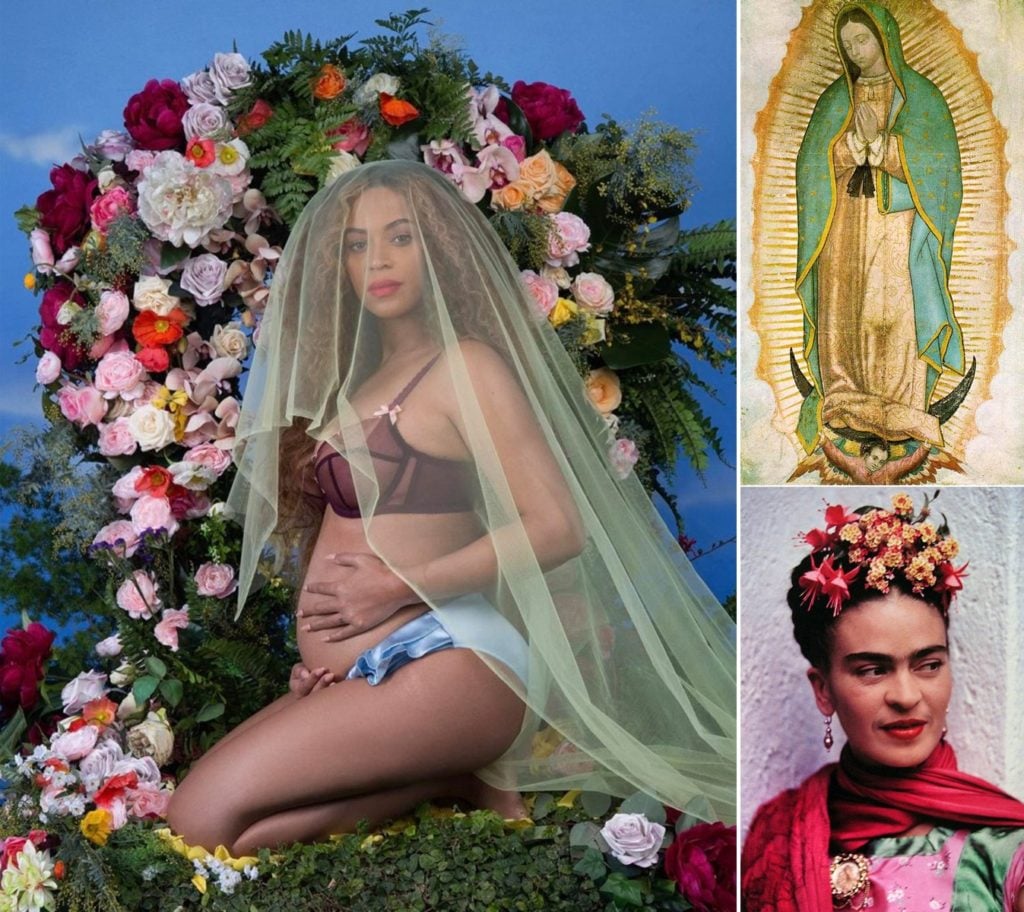

Clockwise: Awol Erikzu’s photograph of Beyoncé; Our Lady of Guadaloupe; Frida Kahlo photographed by Nickolas Muray.

The media frenzy is instant, as everyone rushes to deconstruct and decipher every image. For example, the green veil, New York University art historian Dennis Geronimus tells Harper’s Bazaar, is an homage to Our Lady of Guadalupe, the patroness of the Mexican Catholic Church. Art historian Andrianna Campbell also draws parallels to the work of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo. Frida was a multifaceted woman at the center of her own celebrity and personal hardship, including several miscarriages and a tumultuous marriage to the very high-profile Diego Rivera. It’s easy for Beyoncé to feel kinship.

But what’s most striking in these images are the references to the Roman goddess of sex, love, and fertility, directly alluding to Sandro Botticelli’s 15th-century masterpiece The Birth of Venus. In one of the photographs, Beyoncé is standing naked on a pedestal covered with lush tropical greenery, shielding a breast with one hand, the other holding her belly, while her cascading hair envelopes the side of her body. In another, rendered in black and white, she is sitting on a throne of flowers, her expression more demure, almost virginal. That is, if it weren’t for her expanded midriff.

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (c.1486). Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

I was about seven months pregnant with my youngest son at the end of 2009. One morning in December I headed for Tracy Anderson’s exercise studio in New York City (then in a loft on Hubert Street). I was about to start my daily workout when Beyoncé appeared by my side. More impressively, she saw me. “And how could she not?” my husband said later that day when I told him. Needless to say, I was very noticeable with tight exercise clothes and a gigantic stomach, dancing and contorting in a 90-degree heated room. “B”—also in black leggings and gray tank top, hair up in a ponytail, bare-faced, taller and much more beautiful than in all her pictures and videos—looked at me and my belly with grace, surprise, delight, and a big, warm, Southern smile. “Congratulations!” she said, and we bonded, albeit for seconds, over our womanhood. That day it dawned on me that Beyoncé’s artistry depends as much on her creativity as it does on her empathy, her vulnerability, and her humanity, all quintessential elements for being a true and lasting artist.

Beyoncé dressed as Frida Kahlo. Photo via Twitter.

I tell all my clients when I start working with them that contemporary art is always helping us to make sense (or nonsense) of our own selves and our surroundings while keeping the eye, the mind, and the heart engaged: for the viewer there are so many aesthetic elements to enjoy, so many ideas that a piece of art can generate, and so many emotions that can be felt for which words sometimes don’t even exist. The art of our times sometimes references the past, sometimes tries to unveil the future, but mostly allows us an opportunity to evaluate the present, and on many occasions, it holds up a mirror where we can see ourselves.

Beyoncé, an art collector herself, told the New York Times in a profile about her mother, Tina Lawson, that growing up: “it was important to my mother to surround us with positive, powerful, strong images of African and African American art so that we could reflect and see ourselves in them . . . My mother has always been invested in making women feel beautiful, and her art collection always told the stories of women wanting to do the same.”

It is not surprising, then, that Beyoncé continues to be inspired by art and make references to it every time she has a meaningful opportunity to do so. Art makes life interesting: music, dance, film, visual arts, and performance share this common denominator. All these art manifestations together or alone enlarge our souls, expand our spirits, give us new perspective. Beyoncé combines them all: in songs, images, concerts, and videos that invite contemplation about the African diaspora, about what it means to be a Black woman in America, or simply what it means to be a woman in today’s world.

The ultimate aim of self-expression is an irrepressible need to bridge the gap between one another. The gap that separates us as human beings, that feeling that we all have in our lives at some point or another, that makes us feel misunderstood or alone, can only be closed through our shared universal experiences: those feelings of grief, shame, sexual instinct, joy, sadness, ecstasy, sorrow, fear, euphoria, and love. Artists push innovation and bring new ideas to the forefront by acknowledging the past, sometimes referencing other artists and their artworks, sometimes adding elements like passages from literature, poetry, film, pointing at a socio-political movement or highlighting a moment in history. Artists appropriate, transform, reinterpret, reenact, shape-shift, give credit, and pay homage to those who have paved the way before them.

Screenshots from Beyonce’s “Mine” video.

Beyoncé is a master at exactly such quotations. Take, for example, the video of “Mine,” released as part her 2013 eponymous album. Beyoncé moves slowly, the lighting is pure and clean, she wears a heavy veil and a strapless dress that gives the illusion of marble, like the surface of a sculpture. A male model is resting on her lap. It is a direct reference to Michelangelo Buonarroti’s La Pietà, the Carrara marble renaissance sculpture finished in 1499 and considered one of the greatest works of one of the greatest artists of all time. Later in the video a man and a woman are kissing; their heads are covered with white cloth. They look very much like Belgian surrealist René Magritte’s painting The Lovers. Beyoncé is smoothly mixing Italian Renaissance, surrealism, R&B, and African beats. Talk about modern-day syncretism. And there’s the video of “Hold Up.” Every woman who has ever felt mad, betrayed, angry, invalidated, cheated, vengeful, obsessed, or broken-hearted finds catharsis through the visuals and lyrics:

I don’t wanna lose my pride, but I’mma fuck me up a bitch.

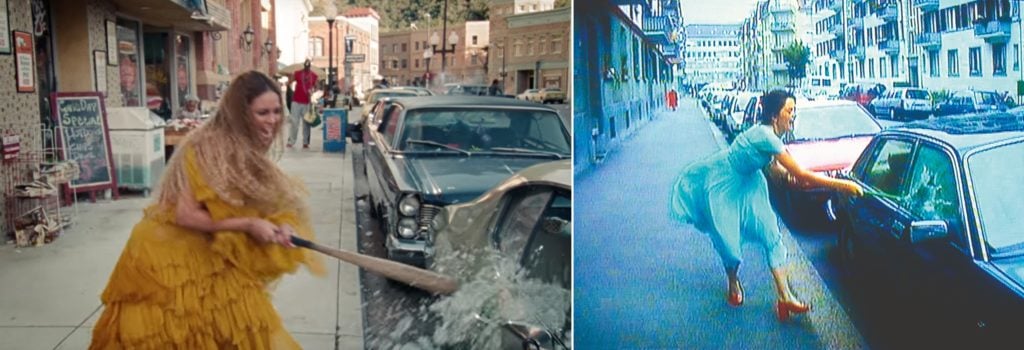

At the crossroads of art, music, fashion, and performance in “Hold Up,” Beyoncé draws inspiration from Swiss artist Pipilotti Rist’s 1997 double screen Ever Is Over All, which debuted at that year’s Venice Biennale. (A Google search of the words “Pipilotti Rist,” an artist who has been working in many different mediums since the early 1980s but whose impact remains in a niche, as in art collectors, museum-goers, art lovers, and connoisseurs, will suggest in third place the word “Beyoncé” next to it, because people want to know how contemporary art has influenced Beyoncé, and in the process, they have learned about many artists, Rist being just one of them.) In Rist’s work, the artist walks down the street wearing a turquoise dress and red heels while smashing the windows of parked cars with an oversized flower in a gracious and feminine way.

Left, Beyonce in Hold Up (2016); Right, Rist in Ever Is Over All (1997). Both courtesy YouTube.

In “Hold Up,” Beyoncé is wearing a flowing, sexy, organza amber dress and black platforms. With fire on her hips and her characteristic swagger, she swings a baseball bat, shattering car windows, store vitrines, hydrants, and video cameras. For both Rist and Beyoncé it’s a paradox: delicate creatures performing aggressive actions while keeping big smiles on their faces.

Afro-Futurism is also part of Beyoncé’s favorite visual genre. In the 2016 video for “Sorry,” Nigerian artist Laolu Senbanjo painted geometric motifs on the dancers’ bodies. He called his paintings the Sacred Art of the Ori, because this practice derives from a spiritual Yoruba ritual. There are clear parallels to the work of Keith Haring and the way he painted on singer Grace Jones’s body for her live performance at New York City’s Paradise Garage in 1985. Beyoncé’s performance at the Grammy Awards in February 2017 right after the announcement of her second pregnancy was also peppered with Afro-Futuristic elements. We see her dressed like a goddess, someone who casts a light into the world as if redeeming the entire Black race. Her dress, created by designer Peter Dundas, was inspired by Gustav Klimt’s golden phase, with elaborate Art Deco motifs inspired by Erté. The gilded halo, although Byzantine in its construction and aesthetics, is a nod to Oshun, whose symbolism abounds in Beyoncé’s videos and performances. Yellow, gold, and amber are the colors associated with the Yoruba goddess of fecundity, sexuality, beauty, love, luxury, and pleasure, all qualities that she embraces and conspicuously highlights with her fertile body.

Still from The Carters, Apesh*t in front of the Winged Victory of Samothrace. Courtesy of YouTube.

Beyoncé and Jay-Z amazed the world when in the summer of 2018 they dropped Everything Is Love. The music video for the first promotional track, “Apesh*t,” was filmed at the Louvre in Paris. The Carters and their dancers move around the regal galleries of the museum creating contrast and tension between their own bodies as contemporary pop icons and artworks like the Mona Lisa, the Venus de Milo, and the Winged Victory of Samothrace, all identifiable historical treasures that have withstood centuries without losing their appeal. I’m particularly captivated by the scene where Beyoncé is with her troupe of dancers, all women whose body types are very diverse, all Black, and all wearing dark-skinned leotards, leggings, and skimpy tops. They look defiantly straight at the camera under the massive painting by the preeminent French Neoclassical painter Jacques-Louis David, The Consecration of the Emperor Napoleon I and Coronation of the Empress Josephine in the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris on 2 December 1804, finished by the artist in 1807 after being commissioned directly by Napoleon Bonaparte.

A still from Jay-Z and Beyoncé’s video “Apesh*t.”

The painting depicts the coronation of Napoleon as the emperor of France and of his wife Josephine, in front of Notre Dame’s altar and a large group of dignitaries, including the Pope Pius VII. What I find amusing, if not subversive, is that Napoleon was described by historians as a misogynist who didn’t see women as equal to men and who called them “nothing but machines for producing children.” He stripped women of many rights, turning them almost into their husband’s property, as written in the pages of his Napoleonic Code. He was an absolutist who censored the press and attempted to control every media that then existed, to turn their words and messages into benevolent propaganda that supported each one of his moves. There is such stark contrast between who Napoleon was and what he represented and the feminist, open-minded, egalitarian, and democratic attitude of Beyoncé, making that scene at the Louvre look and feel like an electric shock to history.

In thinking about her contribution to art and entertainment, to pop culture and to the world at large, Beyoncé has found a way to give new meaning to the power of the image, intermixing classic with contemporary, western with non-western, the divine with the profane. She has created her own language, dignifying and elevating African Americans, women, and freedom of expression. It is acceptable and even desirable to be sexual, to be curvy, to be a muse of many and a muse to oneself, to love our bodies, to love our husbands, to be devoted mothers, and in Beyoncé’s case, to insert herself into the most iconic works of art and to do it tastefully and masterfully in ways that no other performer has ever done. She’s a creator whose indelible mark in our culture has earned her a spot in art history.