Art History

Ukrainian Artist Maria Prymachenko’s Fantastical Visions Have Captivated the World—Here Are 3 Key Insights Into Her Life and Work

An inspiration for Picasso and Chagall, her works are now an international symbol of the call for peace.

An inspiration for Picasso and Chagall, her works are now an international symbol of the call for peace.

Katie White

“I bow down before the artistic miracle of this brilliant Ukrainian,” Pablo Picasso declared upon seeing the works of Maria Prymachenko at the 1937 Paris World Fair. Marc Chagall was another admirer, calling his own images of fantastical creatures “the cousins of the strange beasts of Maria Prymachenko.”

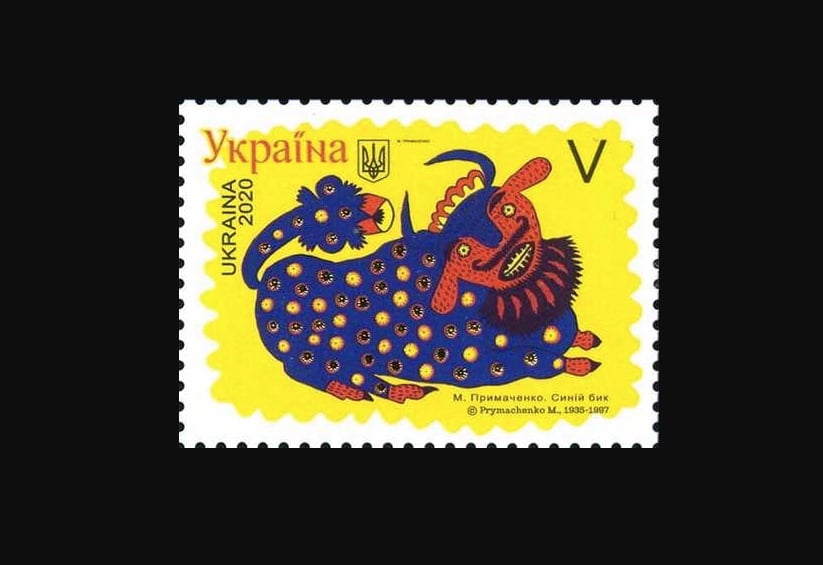

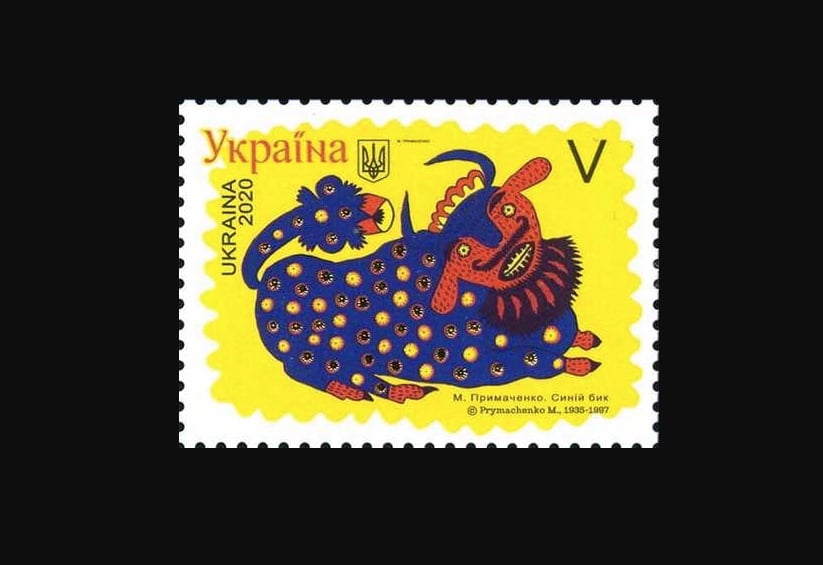

A self-taught artist (1909–1997) born to humble means, Prymachenko earned fame in her lifetime for dazzlingly colorful and wildly inventive scenes of animals—lions, birds, horses, and other beasts—covered in riotously hued, almost psychedelic patterns. She might just be Ukraine’s most beloved artist; her likeness has appeared on stamps and even the country’s coinage.

Recently, he work has come to world attention for a darker reason. On February 28, the Kyiv Independent reported that a Russian attack hit the Ivankiv Historical and Local History Museum, home to over 20 of Prymachenko’s fantastical paintings. According to the Maria Prymachenko Family Foundation, which is operated by her great-granddaughter Anastasiia Prymachenko, a local man was able to save at least some of the works from the destruction.

While much art-historical research on Maria Prymachenko is yet to be translated and digitized, here are three facts about her marvelous creations.

“Naive art” is a term used to describe the works of self-trained artists, perhaps most famously in the case of the French artist Henri Rousseau. Prymachenko certainly classifies as an artist in the naive style—but that is not to say that her works aren’t informed by deep knowledge of a rich cultural tradition.

Born to a peasant family near Chernobyl, the artist suffered from polio as a child, an illness that left her confined to bed for much of her childhood (a later surgery would enable her to walk independently). During those years, the artist’s mother taught her embroidery, a tradition deeply tied to Ukrainian culture. She also learned the art of pysanka, the intricate Ukrainian style of decorating Easter eggs.

During the 1930s, Prymachenko was part of the Ivankiv Co-operative Embroidery Association, where she earned a reputation for her synthesis of traditional Ukrainian designs with her own imaginative creations. These vivid embroideries were in turn discovered in a street market by Kyiv-based artist Tetiana Floru, who invited the young Prymachenko to the Central Experimental Workshop of the Kyiv Museum of Ukrainian Art, a studio where a team of artists was working toward the First Republican Folk Art Exhibition, which first took place in Kyiv in 1936.

Though Prymachenko’s later paintings may at first glance read as fanciful, or even outright silly, they follow her embroidery works in quietly affirming the singularity of Ukrainian culture and identity. In one painting, Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko Arrives From His Exile to Flowering Ukraine (1968), the artist pictures the beloved Ukrainian poet, writer, folklorist, and nationalist Taras Shevchenko returning from an exile imposed for promoting Ukrainian independence.

In another work, from a decade later, Our Army Our Protectors (1978), Prymachenko imagines Ukraine’s soldiers not as military men, but as ordinary men and women, dressed in traditional Ukrainian attire, standing amid tall flowers.

Even the story of the artist’s earliest creative impulse links her quite literally to the land beneath her feet. “Once, as a young girl, I was tending a gaggle of geese,” Prymachenko recalled of her first drawings. “When I got with them to a sandy beach, on the bank of the river, after crossing a field dotted with wildflowers, I began to draw real and imaginary flowers with a stick on the sand… Later, I decided to paint the walls of my house using natural pigments. After that, I’ve never stopped drawing and painting.”

The traumas of war deeply and directly effected Prymachenko’s life. Soon after meeting her partner Vasyl Marynchuk, in 1941, the artist would give birth to a son, Fedor. But the young family would soon be shattered. A soldier, Marynchuk was sent to the front lines of the Second World War and would lose his life. Prymachenko’s brother, too, would be shot by Nazis.

Prymachenko would stop making art for some twenty years, returning to creative work in the 1960s, first through embroidery and then gouache and watercolors. While she would still engage with the folkloric subjects of her early work, her works now drew on her dreams.

Sometimes her dreams would conjure up outlandish scenes such as her work Corncob Horse in Outer Space or Four Drunkards Riding a Bird. Other times, however, her paintings pitted good against evil. We see this in her work The Threat of War (1986) and May That Nuclear War be Cursed (1978). A message of global peace ran throughout these later works, including May I Give This Ukrainian Bread to All People in This Big Wide World (1982).

Today, artists are once again utilizing her work to call for peace in the current war between Ukraine and Russia. American artist Maria Carmen Knecht recently depicted Prymachenko’s work A Dove Has Spread Her Wings and Asks for Peace as a mural in St. Louis, Missouri, and soon after the work could be seen popping up at anti-war protests around the world.

Some have noted that over the years Prymachenko’s works became brighter and larger. While on some level a compositional decision, these changes were also afforded by the increased availability of certain pigments. In 1966, Prymachenko was awarded the Taras Shevchenko National Prize of Ukraine, one of the country’s highest honors, and in the last decades of her life admirers supplied Prymachenko with materials to create larger format works.

That said, her materials remained simple and consistent. She worked with factory-manufactured brushes, painted in gouache and watercolors, and worked on Whatman paper. Despite her popularity, Prymachenko never sold her works for money, instead gifting them to friends and neighbors. She created thousands of works in her lifetime. The National Museum of Ukrainian Folk Decorative Art in Kyiv alone holds roughly 650 works by the artist.