For hordes of collectors, curators and art lovers, there are undeniable bragging rights that come with getting an early glimpse at the Venice Biennale. Almost all artworks and major installations remain tightly under wraps in the two years between each edition.

That’s why, when a profile of the US’s official representative artist Mark Bradford appeared in the New York Times last week accompanied by numerous pictures of his in-progress artworks for the Biennale, no one appears to have been more caught off guard than the artist himself.

“Those are copyrighted images, those are mine,” Bradford told Hyperallergic after the Times profile appeared online. He said the installation had evolved significantly since the photos were taken. “This is the Venice Biennale and no one let me have a voice. No one showed me or asked my permission. My gallery was surprised, the photographer was surprised, and the curatorial team in Venice was surprised. That’s some bootleg shit. This is not acceptable.” The pavilion’s commissioner, Christopher Bedford, also expressed his discomfort with the publication of the images.

In the days following the article’s publication, however, it became clear that the responsibility lay elsewhere. Although Bradford initially indicated that his gallery, Hauser & Wirth, was surprised that the photos had been published, the gallery was in fact the source that provided the images to the newspaper.

A spokeswoman for the Times told artnet News: “The New York Times received the images and permission to publish those images from Michael Plunkett, Mark Bradford’s liaison at his gallery, Hauser & Wirth, and from his publicist Andrea Schwan.”

In a statement, a spokesperson for Hauser & Wirth said: “Several images among those sent were included in error. Mark Bradford was unaware that these specific images were among the photographs provided to the Times until he saw them in print. The New York Times did not contact the artist, the photographer nor Hauser & Wirth to confirm permission for publication of the images, nor to check captions or courtesy information.”

artnet News put this statement to the Times, which offered the following amplification: “It is not the Times’ responsibility to reconfirm permissions granted for images. It’s the gallery’s responsibility, when acting on behalf of an artist, to confirm and clear all images with the artist before they’re sent out for use.”

The kerfuffle illustrates just how high tensions can run in the lead-up to the Biennale, which is the result of years of work and can permanently earn an artist a place in the canon.

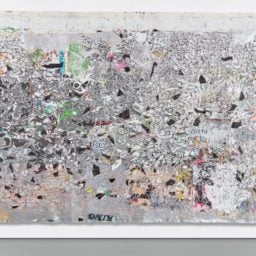

Bradford’s Venice Pavilion is expected to be some of the artist’s most ambitious work to date. The profile lays out how he created a replica of the US pavilion—Doric columns and all —in an effort to infuse some of the Giardini’s storied atmosphere into his Los Angeles work space. After trying roughly ten ways to line those rotunda walls, he wound up plastering them with torn images of cellphone ads found around his neighborhood. (The ads target friends and family of incarcerated individuals by promising them the ability to receive cellphone calls from jail—but it turns out the astronomical rates on such calls can only be described as “predatory.”)

And that’s just the rotunda. The story goes on to describe a massive ceiling-mounted installation called Spoiled Foot, which references the depths of the AIDS crisis, a “Medusa” made of thick black paper rolls, new paintings, and a video in the final gallery. “Building the pavilion was great, because I was making this thing that’s all about power into a safe place where I could play, have angst, fall on the ground,” Bradford told the NYT.

The article’s author, Jori Finkel, a Los Angeles-based contributor to the NYT, said in an email: “I have known Mark for 10 years and believe his exhibition for the U.S. pavilion is shaping up to be his most important and urgent yet. It was really upsetting to me to learn that the very people at Hauser & Wirth who are supposed to represent him failed to get his input on the photos they shared with the Times, creating this whole situation.”

Schwan, the gallery’s publicist, directed artnet News’ request for comment yesterday to the gallery’s vice president, Marc Payot, who in turn directed the request to the U.S. Pavilion’s PR representative David Resnicow, who provided the above statement from Hauser & Wirth by email on Tuesday afternoon. Mark Bradford has not replied to artnet News’ request for comment.

Note: This article has been updated with an additional comment from the New York Times.