People

‘I Don’t Scare Easily’: Martha Cooper on Crawling Her Way Through Train Tunnels to Become One of the Leading Photographers of Graffiti

The photographer is having the largest retrospective of her work to date in Berlin.

The photographer is having the largest retrospective of her work to date in Berlin.

Sarah Cascone

In a photography career that spans six decades, Martha Cooper has broken boundaries and defined genres. She became the first female staff photographer at the New York Post in 1977 and shot seminal images of graffiti and the burgeoning hip hop scene during its infancy.

Now, Cooper is being honored with largest retrospective of her work to date. “Martha Cooper: Taking Pictures,” opening this weekend the Berlin’s Urban Nation Museum for Urban Contemporary Art, charts the artist’s photography, from the pictures taken with her very first camera, which she got when she was in nursery school, in 1946, through the present day.

Curated by Steven P. Harrington and Jaime Rojo, founders of BrooklynStreetArt.com, the show includes images from Cooper’s many books, which feature such as bodies of work as her photographs of women’s breakdancing competitions (We B*Girls); of traditional Japanese tattooist Horibun I at work (Tokyo Tattoo 1970), and the streets of gritty 1970s-era New York City (New York State of Mind).

But it was graffiti that inspired Cooper’s best known work, immortalized in the 1984 book Subway Art, which she published with fellow photographer Henry Chalfant. Cooper was drawn to the tracks by the desire to save for posterity these fleeting artistic creations, which were unlike anything she had ever seen.

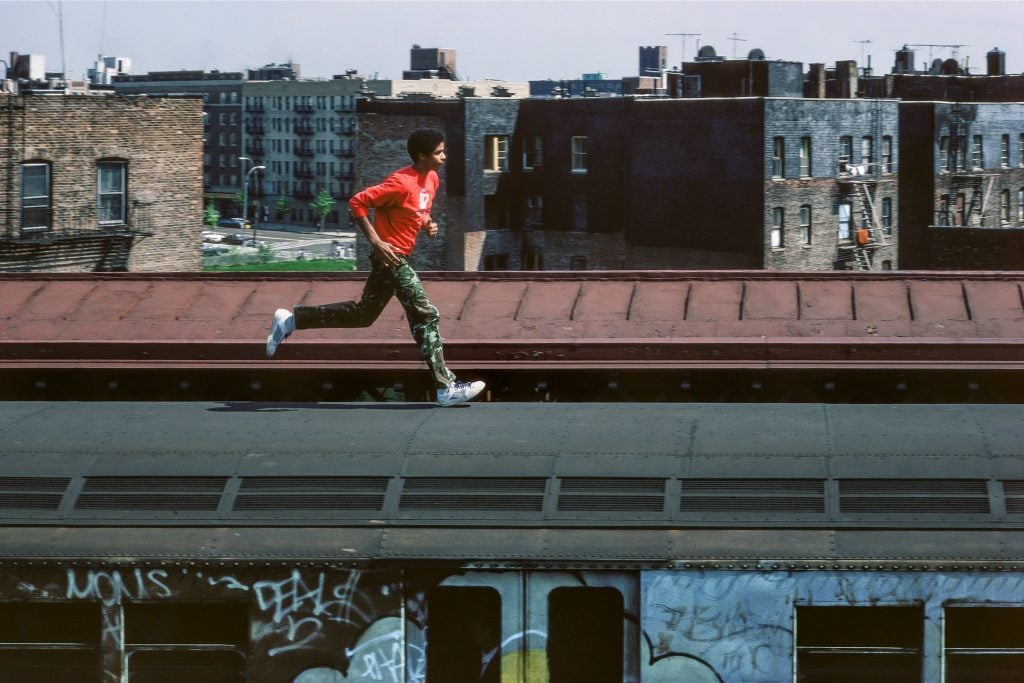

Martha Cooper, 180th Street platform, Bronx, NYC (1980). Photo ©Martha Cooper.

Documenting freshly painted subway cars became an obsession. Cooper spent hours watching trains in the South Bronx, waiting to spot new art. With each frame of Kodachrome film costing 50 cents, Cooper had to make every shot count. Ultimately, Cooper managed to capture seminal images of graffiti in New York back when it was still an underground art.

Artnet News spoke to the artist over email about her career, the evolution of graffiti, and what New York’s graffiti scene is like in 2020.

Martha Cooper, Lower East Side, NYC (1978). Photo ©Martha Cooper.

What drew you to photographing graffiti and graffiti artists?

I was fascinated by the idea that young people had invented their own art world with their own language and set of aesthetics that most adults were unaware of.

In your time documenting the graffiti scene in the 1970s and ’80s, what was the scariest thing that ever happened to you, and the craziest thing you had to do to get a shot?

I don’t scare easily. Remember, I was a staff photographer for the New York Post. We were routinely sent on somewhat scary assignments at night. I guess sneaking into yards and tunnels was crazy, but I don’t remember being scared.

How did you get graffiti writers to trust you?

Writers trusted me because I gave them better photos of their pieces than they could take themselves. At the time few people had cameras.

Martha Cooper, Skeme, Bronx, NYC (1982). Photo ©Martha Cooper.

How has the response to your photographs of graffiti changed in the years since you took those images?

At the time the insides of the subways were “bombed” with tags and most New York City magazine and book editors couldn’t see past the vandalism. Now there is a widespread understanding of the culture and an interest in seeing vintage photos.

How do you think the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter protests have changed the contemporary graffiti landscape in New York over the past six months, and have you been documenting any of the work being made?

I have mostly been staying safely at home and not going out documenting. However, I have heard writers say that the city looks like it did in the ’80s with tags and “throw-ups” (quick pieces) everywhere, especially on shop windows which have been boarded up.

I would not call the Black Lives Matter murals graffiti. Some are literally street art, being painted directly on the street. I noticed that many of the murals are used by news crews as backdrops, so those murals have had unusually high nationwide visibility.

Martha Cooper. Photo by Nika Kramer.

You recently posted an old photo of a Twin Towers mural painted in upper Manhattan in 2002 on Instagram. Do you see any parallels between Black Lives Matter protest art and coronavirus tributes being created by artists now and the 9/11 memorial murals created in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks?

Memorials painted by graffiti and street artists were popular in the 1990s. You can see photos of them in my book with Joseph Sciorra, R.I.P. Memorial Wall Art, published in 1994. September 11th and COVID memorial murals continue in that tradition, which is more a community street art tradition than a graffiti one.

How many of the 9/11 murals do you think have been maintained over the last 19 years, and how important is it to create a record of street art and graffiti made in response to times of crisis?

I don’t know of any 9/11 murals that have been maintained, although there probably are some. Photographs of outdoor murals will inevitably last longer than the art itself. That is primarily why I am interested in photographing and archiving this art. Because graffiti and street art are ephemeral, it is always important to document the works, not just in times of crises. The photographs tell the history of the art form as well as being a response to current events.

What are your feelings about illegal graffiti versus sanctioned street art, and why is it important to you to make a distinction between street art and graffiti?

Graffiti, often called “style writing,” is a form of writing with its own rules and aesthetics. The heart of a graffiti piece is the styled name of the writer. The tools of graffiti writers are generally spray paint and markers. Street art relies on images, not letters, and the materials can be anything. I’m a fan of illegal graffiti.

I love the idea that the writers are creating for themselves and their peers who recognize what they are writing. Illegal graffiti is subversive. It has to be written quickly in appropriated public space. Street artists can take weeks to finish a big piece. Of course there’s an overlap between the techniques of graffiti writers and street artist, and some do both well. I just want people to understand the difference.

“Martha Cooper: Taking Pictures” opens at the Urban Nation Museum for Urban Contemporary Art, Bülowstraße 7, 10783 Berlin, October 2, 2020. The opening will be broadcast online with livestream tour of the exhibition on October 2 at 8 p.m. CET.