Martine Syms’s debut feature film The African Desperate, starring actor and artist Diamond Stingily, takes us on a journey through the final day of an upstate New York MFA program. The action begins at the final critique of Palace Bryant (Stingily), the last requirement to earn her Master of Fine Arts degree at nomen à clef Grio College. (Syms is a graduate of Bard, where much of the film was shot.)

With a hilarious mix of praise and pretension, notable faculty members congratulate Bryant. She packs up her art studio with plans to leave New York to care for her mother in Chicago. Hijinks ensue—there are encounters with frenemies, substance-fueled studio hangs, and an idyllic Hudson riverside picnic with best (art) friend Hannah (Erin Leland). The film is a satire of the MFA experience, poking fun at the desire to belong, the narcissism of the creative class, and the realities of making it in the art world beyond the privileged gates of contemporary cultural production.

In advance of the film’s premiere in Brooklyn last month, I spoke with the Los Angeles-based artist about how it all came together and how the end result reflects her own collaborative practice and experiences in the academy and beyond. Like many, I first encountered Syms’s work at the 2017 Whitney Biennial, where she presented Intro to Threat Modeling, a video letter reviewing semiotic lessons on personal strength and risk-taking, exhibited in the same year she graduated from Bard.

The African Desperate touches on themes that appear throughout Syms’s oeuvre, including the study of R&B and club music, Black poetics, art history, cinema, T.V., and video games.

In addition to the film release, the artist has three concurrent solo exhibitions on view now: “Grio College” at the Hessel Museum of Art at her alma mater, “Neural Swamp” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and “She Mad: Season One” at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. The three shows reveal the breadth of Syms’s practice, which encompasses drawing and photography, A.I. and machine learning, and the first season of a semi biographical sitcom.

Syms is represented by Bridget Donahue in New York, Sadie Coles HQ in London, and recently signed with Hollywood agent CAA. She was insistent about having The African Desperate shown outside a gallery context; the film premiered at International Film Festival Rotterdam and is now streaming on MUBI, a platform for artist-made videos.

As Syms told me in regard to living with the tensions of being, belonging to, and leading in the art world: “Buckle up!”

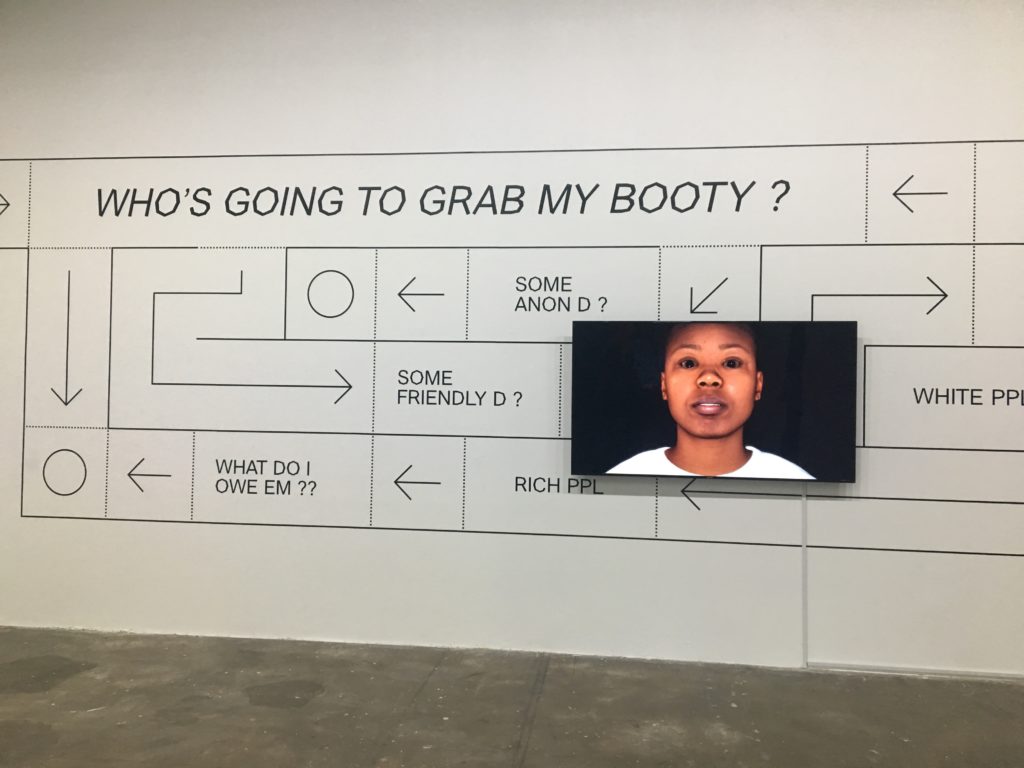

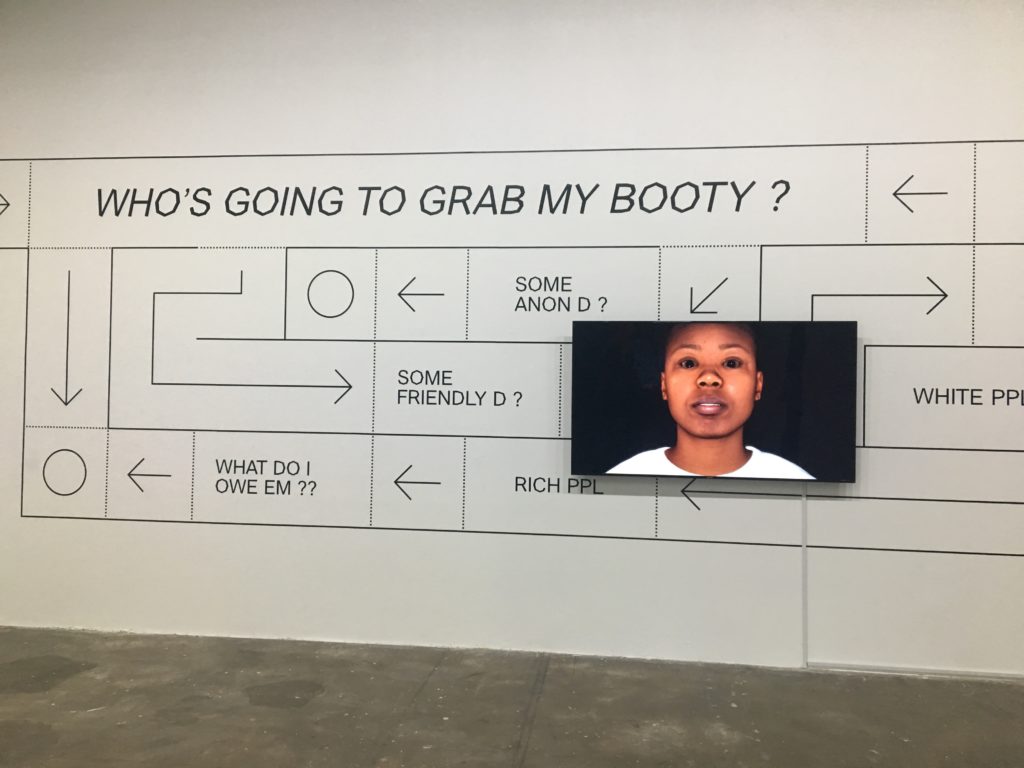

A still from Martine Syms’s The African Desperate (2022). Courtesy of Dominica Inc.

The film opens with an art-school crit—a way of bringing art back to bear on the experience of going to art school in the 2010s. Watching The African Desperate made me think about what performance and pedagogy have in common and the way that art might be the best vehicle for learning outside of the ivory tower.

Essentially, I wanted to have that first crit scene address every theme that was present in the movie. I want it to be a microcosm of every conversation that Palace was going to have for the rest of the film. We [Syms and cowriter, Rocket Caleshu] were interested in baking in the crit, and we used this scene as an entry point, as a way to reflect on discourse. It was important for me that it felt like what it’s like to experience a critique and not just represent it. So the viewer is in the character’s position.

How did you write with poet Rocket Caleshu?

We write a lot, and we write a lot together. He’s a poet, but we worked together on many past installations and videos, so it’s actually really natural. And Diamond [Stingily, who stars as Palace Bryant] is a good friend of mine. And she had talked about wanting to act more. I told her, “If I wrote something for you, would you do it?” So through conversation with her, I had the initial idea. Over Christmas and top of the year last year, I just wrote a real vomit draft. And then we [Rocket and I] wrote [the rest of] it pretty quickly. We have a rapport. Both of us are really interested in poetry—that’s part of why we are interested in having a script put out by NightBoat, which is a poetry press we love. So maybe there are things in the written screenplay that you wouldn’t find in the film. It was important for us that something work on a page. And some things change, obviously, because of production, because of performances, because of actors, because of all of the magic that goes into making a movie.

It’s a very lyrical script.

Yeah, exactly. We were really having fun and not only with the process, but fun with language… There’s a part in the script where we describe these DJs like cyborgs, and the script supervisor was like, “So in this scene, is there gonna be like a robot or something?” And we were like, “No, we’re just having fun with language.”

A still from Martine Syms’s The African Desperate (2022). Courtesy of Dominica Inc.

You’re clearly having fun making this world and enjoying your love of language and cinema. But when you go to grad school, you’re meeting pretentious people who sometimes don’t even care about learning.

We’re all there for different reasons. I’m going to talk about the American education context, because that’s the one I know the best. There’s this false premise that you are all equal. And that you’re starting from the same point, that you want the same things, and that you’ll go to the same places. And at the same time, every single person knows that’s bullshit. And that is one of the central paradoxes of education, and the one that I found most perplexing in grad school, because it was where I had the most disparate experiences. People are all coming from very different experiences. And there’s this illusion or fallacy that now that we’re all going through this program, that it’s an equalizer.

So if the expectation or the false premise is that everyone’s equal, and yet at the same time, everyone knows that that is not the case, then how do you deal with that in real time? How do you manage that as a Black woman?

That’s one of the tensions, the tension of participating…I think that another thing I was interested in from my experience, but also from Diamond’s, is that sometimes that’s just the cost of participating and there are losses with that, but there’s also lots to gain. If you want to do it, buckle up…I want to also think about how those things can be animating. I really like to be in balance, kind of at zero. So I’m always trying to fix or solve tension or address it or confront someone—it’s very hard for me to sit with it. But over the years, I’ve taught myself that tension is not a bad thing, and it is part of what is just omnipresent in life. I’m not condoning it…I remember reading an interview years ago with [fashion photographer] Shaniqwa Jarvis, whose work I love. And she talked about it. She started working in a fashion space and she was just the first Black woman a lot of people had encountered as the photographer. And yeah, that’s part of showing up, being in public.

Absolutely.

I want to show that Palace is ambitious, but also the arc of the film is about her surprising herself. And that’s the real journey that you’re on in any creative pursuit. No artist’s path is the same. You have to trust your own path and you will surprise yourself. And those are actually the moments of transformation and beauty. I love the sublime. So I’m pro transcendence. I know some people aren’t…. But I’m very much always looking for transcendence.

A still from Martine Syms’s The African Desperate (2022). Courtesy of Dominica Inc.

I see you working in a lineage informed by my favorite philosopher and artist, Adrian Piper. As a conceptual artist, Piper uses language as a tool to address cultural forms. And what I noticed about your language in the script of The African Desperate is that it seems to incorporate every single possible U.S. cultural reference.

If you’re talking about ad libs, you could have people referencing R&B and cars like that. Those are my favorite parts, too.

Collaboration is a huge part of everything that you’re doing, from your imprint Dominica Inc to your NTS Radio show “Double Penetration” and now your debut feature film. You’re teaching people through language, which includes music, sound, and gesture, that we have access to and can learn from among many possible overlapping worlds.

I’m about to quote Fred Moten right now, whose book In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition is a life-changing, world-shattering text for me, as was The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study. But the part I liked when I co-taught Moten with Harry Dodge was at the end of The Undercommons when Harney and Moten are talking about the moment of Marvin Gaye’s Let’s Get It On where the conversation becomes a song. And I think of this as a parallel to what teaching should be like. That’s what part of my pedagogy is about: it’s study, that’s the term that Moten uses. Study is always happening everywhere, all around us. I’m really just trying to turn the conversation into song. It’s that moment that is really interesting to me.

In reference to Piper, I mean, one of my favorite projects is Letters to the Editor. I like the directness of it, I love the way they’re written—they’re also hysterical. It’s clear she was studying philosophy, and there’s one that’s like a philosophical proof or permutations of being Black, being an artist, being a woman. In another, she’s annotating the editors of the New York Times, critiquing them, fact-checking, and showing off her virtuosic mind in a way that’s really funny, well-written, and really entertaining. Obviously, there are other projects that I love. But that is a part of Piper’s practice where she showed me what being an artist participating in the world could look like. Just one way.

Martine Syms, Threat Model and Mythiccbeing, (both 2018). Photo: Hili Perlson.

I’m excited about how you’re changing up the game for the distribution of moving Image work that would be seen in the gallery but also might need to be streamed here and right now.

I had a really amazing conversation with Chrissie Iles, a curator at the Whitney, just before I went into production. Creative Capital was one of the grants I won that helped make The African Desperate possible. As part of the grant, you do these one-on-ones with mentors at the Creative Capital retreat for awardees. The way my life looks as a gallery artist, this could have been a noncommercial project for me, or I might sell it to a distributor. I don’t know how it’s going to exist in art. And Chrissy really challenged me to re-conceive that and said, “Why can’t it still be collected by an institution and collectors as well. Why can’t it be both?” She just threw it back to me, “We get to create what’s important art. So get that anxiety out of your mind, and just make your film.”

Written and directed by Martine Syms and starring artist Diamond Stingily, The African Desperate is co-written by Rocket Caleshu and edited by Nicole Otero with cinematography by Daisy Zhou and an original score by Aunt Sister, Colin Self, and Ben Babbit. The film is now streaming on MUBI.