Politics

How Artists Are Memorializing Victims of Mass Shootings, Again and Again and Again and Again

In a grim indicator, local governments have created official processes for building monuments, sensing that more will come.

In a grim indicator, local governments have created official processes for building monuments, sensing that more will come.

Zachary Small

Matt Kenyon had already planned a memorial to the 10 victims of the teenage gunman who rampaged through a Buffalo grocery store in May. During the closing of his Brooklyn exhibition, “Wolf at the Door,” the artist presented a stack of papers with the names of U.S. school shooting victims since the Columbine High School massacre in 1999.

That grim information goes unnoticed to the naked eye, however, because Kenyon micro-printed the names as alternative rule on stationary. Altogether, the names appear like the lines on which students would practice their cursive. Viewers were encouraged to take a page and write to government officials about the importance of gun-control legislation, ensuring the names of the many dead—however invisible—are archived into public record.

Then another shooting. Nineteen students and two teachers murdered by another teenage gunman in Uvalde, Texas. Kenyon packed his bags and returned upstate to Buffalo, where he works as an art professor for the State University of New York at Buffalo.

On Wednesday, he staged the “Alternative Rule” project inside a bookstore just a few blocks away from the shuttered Tops grocery store. More than 50 visitors participated in the letter-writing event, which Kenyon hoped would provide solace to the community.

“It’s all pretty raw here,” he told Artnet News. “People are feeling powerless right now.”

That same evening, three more shootings were reported: one at a hospital in Oklahoma, another at a Walmart in Pennsylvania, and a third at a high school in California.

Kenyon said that given the increasing rate of deaths by gunfire, he is already planning to print a second edition of “Alternative Rule” with the names of more children who have died.

“I want this project to be a vehicle for people to push for the change that needs to happen,” Kenyon explained.

Volunteers writing letters as part of Matt Kenyon’s “Alternative Rule” project. Photo courtesy the artist.

Over the past 50 years, mass shootings in the United States have become more frequent and more deadly. Although there is no universally accepted definition of a mass shooting, the Congressional Research Service defines it as any event in which four or more victims are killed in public with a firearm. In 2019, a nonprofit called the Violence Project found that the deadliest assaults, often involving dozens of victims, have occurred in the past five years, including the 2017 Las Vegas shooting that claimed an unprecedented 58 lives.

Artists have attempted to visualize the psychic scars and immeasurable grief that visits communities mourning the dead, but the frequency of the attacks has turned the memorialization of shooting victims into its own genre. And in recent years, local governments have created official processes for building monuments, sensing that more shootings are on the way.

Earlier this year, city officials in El Paso, Texas commissioned the painter Tino Ortega to design a permanent memorial for the 23 victims who died in the Walmart mass shooting in 2019. Following the tragedy, Ortega started painting murals around the city, one for each lost life. He has finished 10 of those artworks in the last three years, but plans to keep going even as he develops the official memorial. The murals featured balloons to uplift the community’s spirits; the memorial will resemble a crown to symbolize the dignity of those killed.

“My art isn’t there to stop the main problem,” he explained. “The art is there to help comfort those in the community.”

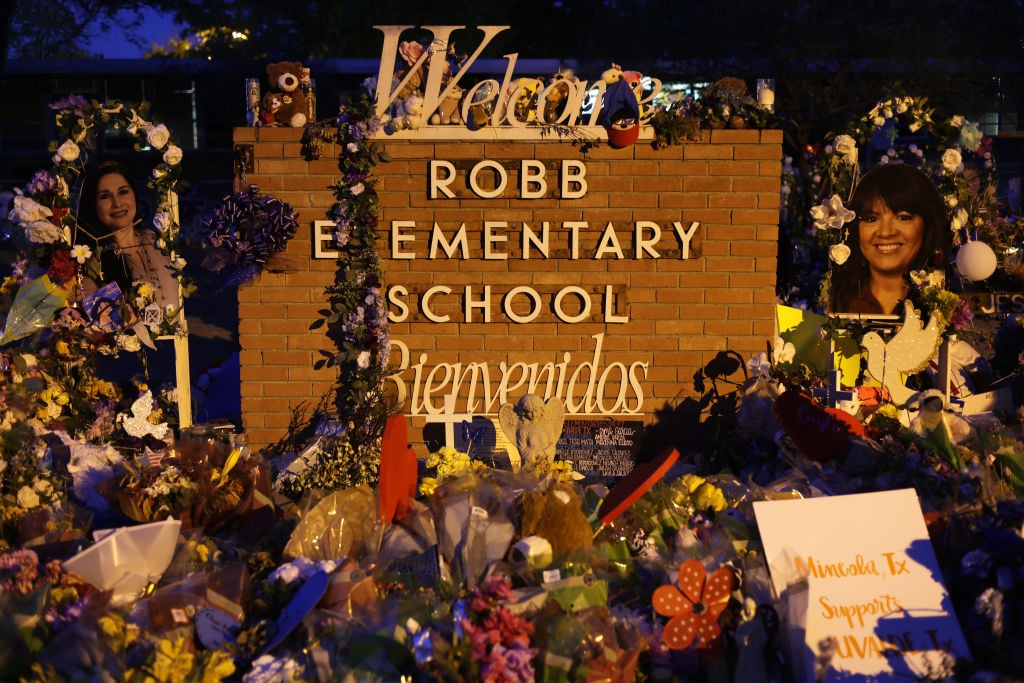

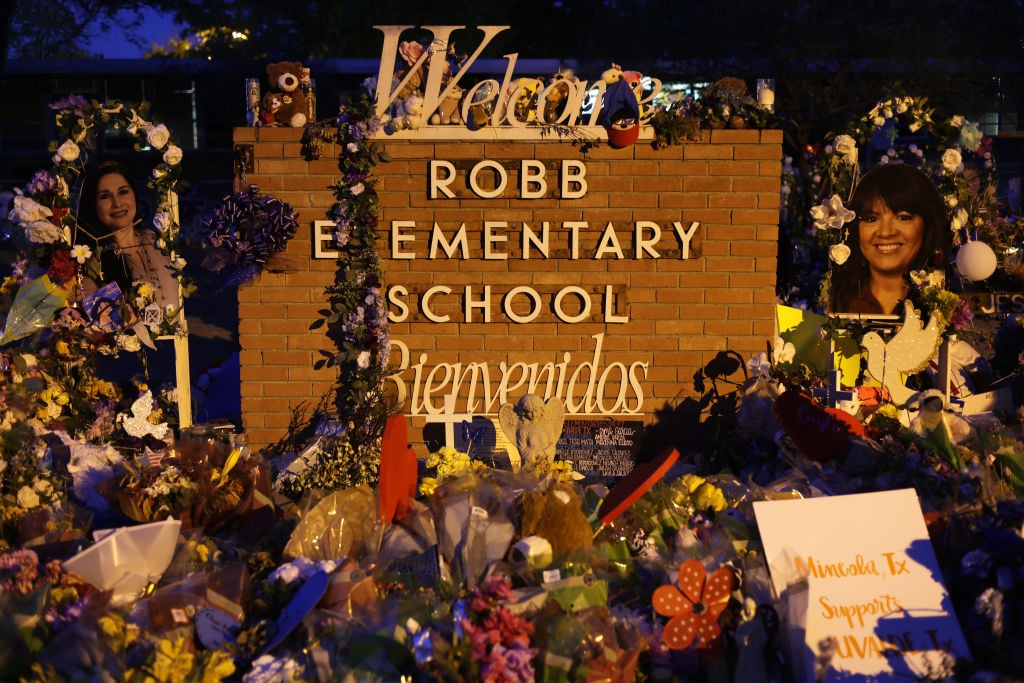

A memorial for the 19 children and two adults killed on May 24th during a mass shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas. (Photo by Yasin Ozturk/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

Similar state-commissioned projects are in the works elsewhere. In 2019, the artist David Best gathered with Coral Springs, Florida residents to mark the one-year anniversary of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting by burning a monument to the ground. The temporary plywood structure, called “Temple of Time,” was torched in an act of communal mourning.

Three hours north of Orlando, some families of the 49 victims who died in the 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting are now awaiting the opening of a $45 million museum and memorial complex. The project recently entered its final design phase, with some survivors complaining that it would turn their trauma into a theme park.

And in Las Vegas, city officials have announced that it will start accepting design proposals in July for its planned memorial. “Ours is not a typical art project,” said Tenille Pereira, chair of the memorial committee and the director of the Vegas Strong Resiliency Center, which serves those affected by the Route 91 Harvest Festival shooting. “One of its main purposes is to lead a healing process.”

Paul Farber, the director of Monument Lab, a nonprofit that tracks the nation’s commemorative landscape, said that it’s hard to measure just how many memorials have been created to honor victims of mass shootings because many, like Raihl’s mural, function as temporary shrines.

“Art and expression are fundamentally connected to the multiple ways that we as a society are responding to this crisis,” Farber said.

Indeed, in times of emergency, grassroots memorials and unsanctioned artworks become central to the healing process. In the aftermath of the Uvalde shooting, Janel Raihl started painting a mural in her Las Vegas neighborhood on a 60-foot-long-wall donated by a member of her community. She filled the space with hearts as dozens of passersby stopped to help finish the artwork. Local news media also documented the event.

“One of the media people showed up in the morning while I was priming the wall,” Raihl said. “But they had to leave because there was another shooting.”