Art World

Cold Wave in Milan Damages Masterpieces at Pinacoteca di Brera

The museum's director, James Bradburne, is facing backlash from Italian experts.

The museum's director, James Bradburne, is facing backlash from Italian experts.

Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

The cold wave that’s currently upon Italy has caused a storm at the heart of the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan, where two 15th-century paintings were rushed to the museum’s conservators after the spell of dry cold shrank their wooden backings and made their paint buckle.

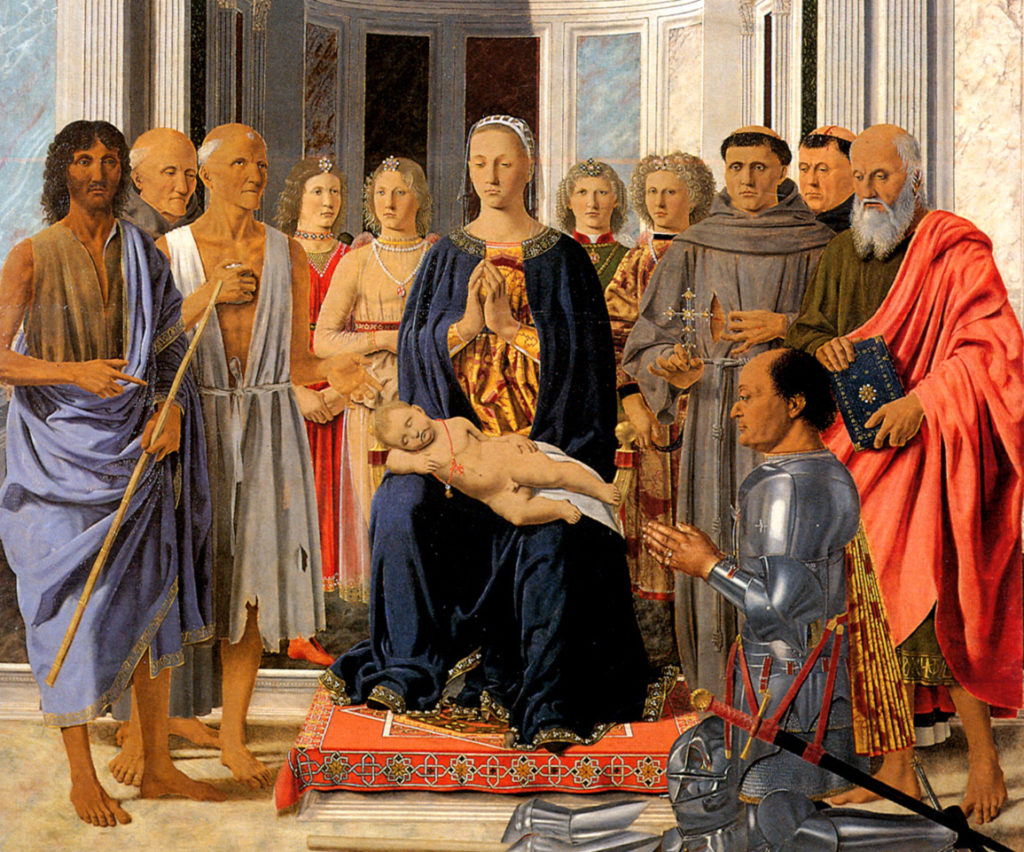

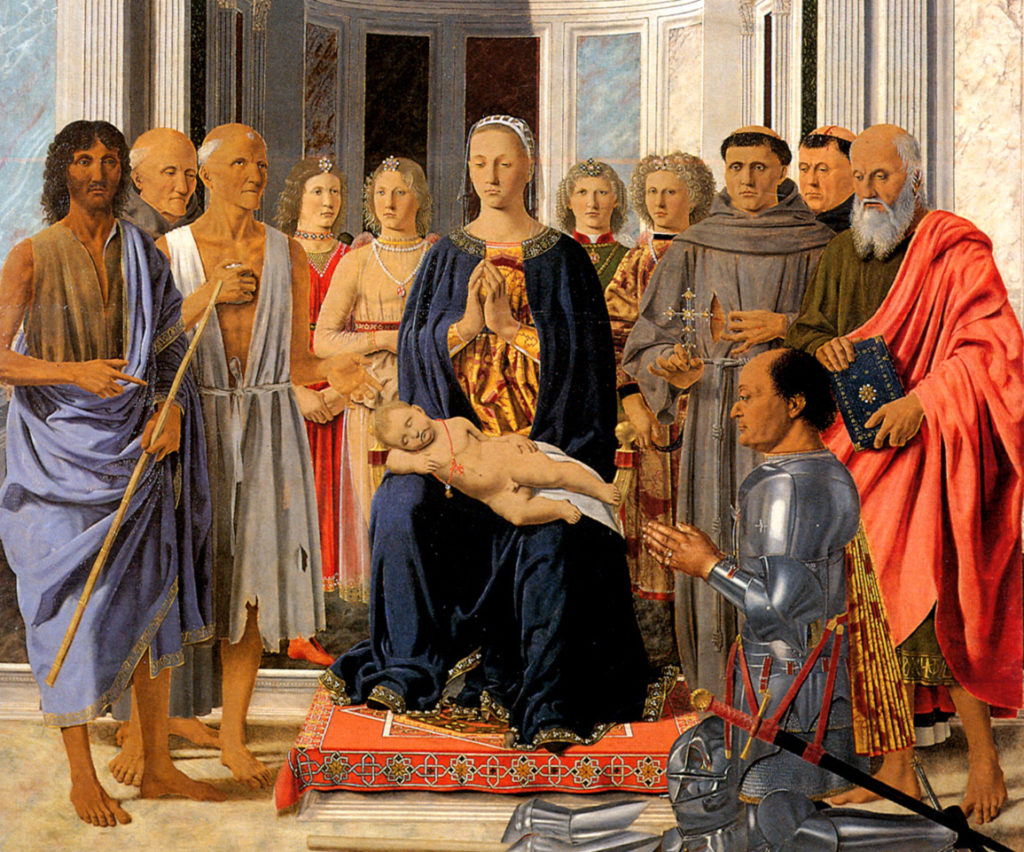

One of the damaged paintings is Bramante’s Christ at the Column, the Times reports. Another 40 paintings at the museum, including masterpieces like Piero della Francesca’s Pala di Montefeltro, have been left on display, but strips of thin paper have been applied to their surfaces to prevent the paint from falling off.

The director of the museum—which has paintings by Caravaggio, Andrea Mantegna, and Raphael in its collections—is James Bradburne, one of seven foreigners among a slew of new hires picked by the Italian government in 2015 to modernize its national museums and gear them towards profitability, by implementing strategies including the staging of blockbuster exhibitions, and the development of visitor services like cafés and shops.

“This was a natural disaster—the things that a museum professional hopes will never happen happened,” Bradburne told the Times, referring to the dry, cold winds blowing from the Alps that made the humidity in Milan drop to 20 percent, starting on January 7.

“It is the first time the humidity has dropped so rapidly in a decade and the climate system, installed in 2004, could not cope. Back then they didn’t foresee this kind of perfect storm. I am not pointing fingers because we still don’t know exactly what happened.”

James Bradburne in Milan in December 2016. Photo by Stefania D’Alessandro/Getty Images.

But the Canadian-born museum director has nevertheless been lambasted—a backlash that has been deemed as “nationalistic” by the Times—for his management of the incident.

“Today the Pinacoteca di Brera looks like a museum of a country at war, a bombed city. Almost 50 paintings (some of them masterpieces) have undergone such a change in temperature and humidity as to risk losing large areas of painting. And no restoration can undo this damage, although it will be possible, one hopes, to minimize it,” Tomaso Montanari, a leading art historian, wrote in La Reppublica this past Sunday.

“[…] I wonder if this sort of conservation catastrophe could have happened in a museum led by a true director: that is, by an art historian, as is the case in all the great museums of the world. Instead, the museum reform implemented by the Renzi government has provided otherwise, and now at Brera there’s a manager who until yesterday was organizing exhibitions, and that now is worrying exclusively about marketing. And the question is: is there a connection between these two things?,” Montarani continues, criticizing both the government’s policies and Bradburne.

“We reacted with enormous professionalism. The four restorers on the staff were rushing around with magnifying glasses to check paintings, and we used our own lab for restoring the Bramante. I don’t know of another museum that could have responded so well and so quickly,” Bradburne told the Times, defending himself and his team from the accusations.

“As for the paintings to which we have applied paper Band-Aids to keep the paint intact, we can remove them as the wood expands,” he explained, adding that humidifiers at the galleries are checked three times a week.

Caravaggio, Judith Beheading Holofernes (circa 1607). Courtesy of Cabinet Turquin.

According to the Times, resentment towards Bradburne in the Italian community started building up last year, when he controversially decided to display a painting depicting Judith and Holofernes that was discovered in the attic of a French apartment in 2014, and which was attributed by some experts to Caravaggio.

Bradburne hung the disputed painting next to a bonafide Caravaggio, which made one of the experts from the museum’s committee resign on the grounds that the decision would make the museum lose credibility.

“It seems what happened [as a result of the cold wave] has been used by some to prove my hiring was a failure. It has not—I believe stewardship is a prerequisite for making art accessible,” Bradburne told the Times.

“This museum has been a flagship for the government’s reforms, so for anyone wanting to take a swing at those reforms, this is a good target.”