People

Actor Matt Dillon and Artist Jesper Just on How They Collaborated on a New Video Work Shot Almost Entirely Inside an MRI Machine

"The doctors called Matt's one of the top 20 best brains they had ever seen," Jesper Just said.

"The doctors called Matt's one of the top 20 best brains they had ever seen," Jesper Just said.

Osman Can Yerebakan

Last spring, the actor Matt Dillon and artist Jesper Just started a conversation over currywurst outside of a former World War II bunker in west Berlin. It was during the opening of Dillon’s painting exhibition at Der Spiegel art critic Ingeborg Wiensowski’s art space, where Just was also participating in a concurrent video art group show.

“I’ve always had more of a connection with artists than with people in my industry,” Dillon told Artnet News.

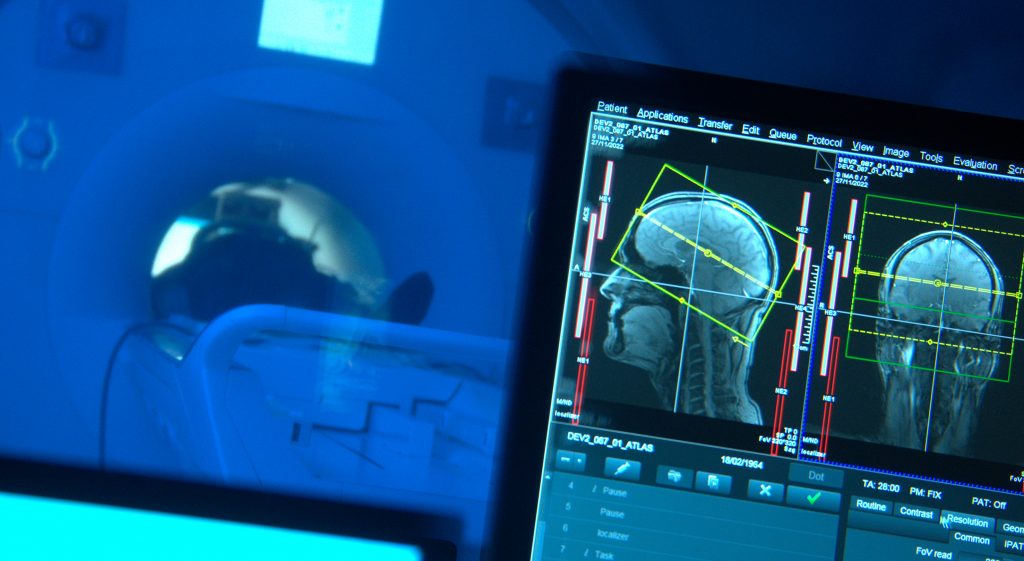

Soon after, the duo met again in New York, where Just inquired about whether Dillon might star in his next video work, Interfears. The 16-minute film follows the contemplative musings of a man locked inside an MRI machine. It takes the viewer into his brain—literally and allegorically—where he tries to perform different emotions, much like in acting, the results of which appear in his neurological scan.

Dillon had just wrapped a shoot in Greece, so the timing worked. And, although the actor wasn’t keen on lying still inside an MIR tube for hours, the challenge intrigued him. Last October, at a research center and a hospital in Paris, the shot the film over two days, in between emergency use of the machines.

Perrotin gallery debuted Interfears at L.A.’s historic Del Mar Theater in February. (The premiere was the gallery’s test run for the venue, which will become its permanent West Coast space later this year.) It is currently on view at MAC Lyon until July, and just went up at Just’s exhibition at Copenhagen’s Nicolai Wallner gallery on April 14.

In Just’s signature style, clinically clean-cut shots are set against the sound of the scanner’s cold industrial noise, as well as the moody melodies of Gustav Mahler’s 5th Symphony Adagietto. At the same time, the deadpan protagonist recounts spontaneous experiences which he tries to reignite inside himself, all while staring into a scanning tube decorated with calming images of palm trees.

Recently, we sat down with the duo at a table at Perrotin gallery in New York to discuss how they rely on each other’s intuitions, the difference between real and artificial emotions, and how Dillon got over his claustrophobia.

Jesper Just, production still, 2023. Courtesy Perrotin and Gallerie Nicolai Wallner.

Matt, how was the experience of acting almost entirely inside the MRI machine?

Matt Dillon: The doctors were very helpful and they told me I can always get myself out, which helped. I was happy to be of service to Jesper’s vision. We were going back and forth with ideas and I even contributed some of the words the character says. I had felt this type of collaborative energy with Lars von Trier, too. When I was playing a character, I was slowly understating what he was really trying to do.

What is the difference between working with a film director and an artist who makes video works?

MD: There is a trust factor in both. But I will give a lot more leeway to an artist, because it’s a conceptual idea and it’s almost fully their vision. If I agree to do that, then I’m agreeing to go all in for what the artist’s vision is, unless it is something extreme that I will not do.

There are films that producers call “art house” of course, like those by David Lynch or Jim Jarmusch, for example, but Jesper’s medium is art. The commercial considerations are perhaps less, but of course art is a business too. There is less compromise in this experience—executives in the film industry are obsessed with what road the characters go down, and there are so many moving parts in a movie. But in short, I told Jesper “let’s go down with what you want,” and my only concern was how to spend so much time inside the MRI machine.

Jesper Just: The doctors were actually amazed that you went back again and again, despite your claustrophobia. We actually did real MRI scans, so what the audience sees in the work is Matt’s brain. The doctors called it one of the top 20 best brains they had ever seen. They wouldn’t be allowed to release the footage if they had found something wrong with the results.

Jesper, did you have a vision for a work about the performativity of emotions for a while or did the idea come up after befriending an actor?

JJ: I had the idea for years, initially as a prologue to a bigger project to set the tone, but it eventually became its own work, partially due to Covid. The idea in a way came from my project with ballet dancers, Corporealities, which I had shown at Perrotin right before the pandemic. Some romantic classical music was sent directly into dancers’ bodies with electric pads to control the muscles. The idea was to remove that sensibility of harmony with music from the dancers. The muscle stimulation that is a part of dancing had suddenly become visible with the wires. This led to another idea about acting and representation of emotions. I was curious to explore the emotional topography of an actor creating emotions. It’s not science but something else. What do you do with your ego when you are playing a role? Are you possessed? Are you still aware of who you are?

Jesper, your work has mainly been about stimulation that interrupts the body from outside, such as the project with ballet dancers, but this time the idea was to cultivate emotions from within the body.

JJ: There are multiple layers of this representation. Matt is there of course as a real person whose brain scans we’re seeing. But at the same time, he’s also acting as a person who is not capable of feeling an emotion. We are monitoring his brain going from there to starting to feel something with the music playing. In studies, some psychopaths who are not capable of feeling empathy start feeling things when they imagine music; they’re triggered through the audio cortex. I was very curious about this effect of music. We see him being more and more analytical about his feelings and speaking about them. I see this a bit as the border between person and persona, which I like to blur.

Did the fact that you’re shooting a work of video art give you the freedom to improvise with your text and acting?

MD: There was a clear written monologue, but I was improvising some of most part. Directors rarely say “slow down,” except Scandinavian directors. The idea of the audience becoming uncomfortable, restless, or confused has nothing to do with how long the movie is, but has to do with pace. A short film can feel very long, too.

Matt, how did you connect with the character, who for the most part is aloof?

MD: In this particular case, there was no background or a completely constructed script. You can’t play a character if you’re judging the character, so I had to go with it to reflect the emotional life of an individual. Music was an important part because somebody’s emotional reaction to music says a lot. I felt empathy for the character. What we’re doing is more about the actions. We don’t focus on emotion —it’s all behavior. And then the emotion comes out.

Jesper Just, production still, 2023. Courtesy Perrotin and Gallerie Nicolai Wallner.

The MRI room must have created its own challenges for both you.

JJ: The neurologist was there to help us with the scans. I’ve always been interested in concepts that came before cinema, for example garden design. When you go into an English Romantic garden, you see they have created a narrative with the way they invite you to discover emotional sensations around different small paths. The experience comes from moving which is very important for the camera, as well. We were inside a magnetic field, so we could not have a dolly or drive the camera around. The camera was outside shooting through the window, but I still wanted that movement effect. As a result, the camera is constantly spinning with zooms into the brain.

Matt, how did you feel going into shooting something that was not a long feature? Did those sentiments change after it took place last fall?

MD: The thing that applies to both experiences is to keep things emotionally truthful. When I did The House That Jack Built with Lars, I had talked about this with [actor] Bruno Ganz—after spending 10 days inside a freezer for the movie, it had just felt a lot. In this case, I didn’t have to commit to things like learning a dialect or studying a long text, but it was more about working on the emotional environment. In my experience, it’s not alchemy—it’s what we do, not necessarily technical, but rather a craft.

Was there a trick you used to get through your time in the MRI tube?

MD: At some point, I was listening this 1920s dance song called Concentratin’ (On You) by Jack Purvis. It was constantly playing in my head, and I slowly realized the song was about concentrating, in this case on the woman he was singing about, but it later occurred to me that it helped me get through the process.

It must have been fun to engage with the idea of the artificiality of emotions, which is a core experience of traditional movie making, but almost never its subject.

MD: They say directors make a film three times: one before making it, later while shooting it, and then in the editing room. I am wondering if Jesper felt that way.

JJ: Once the film has been shot, I don’t look at the script again. I look at the material, and try to make the best possible film out of it.

MD: And that is usually when the movies come out the best.

Matt, you’re also a painter. How did it feel to explore video art?

MD: I’ve always been interested in conceptual art. I used to hang out with Mike Kelley through a gallerist friend in L.A. And, I’ve made some odd movies, like Mimic with Yorgos Lanthimos, which we shot in Mexico City—definitely one of the oddest movies I’ve ever made. Eventually it is about the director. The buck stops with Jesper—I respect him as an artist. In my heart I know my ideas are not as good as my mistakes, or that’s how I work. I need ideas, everything is an idea with painting or another medium. Jesper and I recently went to Nino Mier Gallery’s opening for André Butzer who is a great painter and a friend of mine.

Jesper, how was it different working with ballet dancers and then an actor? They are all performers, but different in training and approach.

JJ: With dancers, I had to learn how to work with them because I was invited for the project. Dancers express a movement with their bodies and then they get critiqued for it. Actors are used to talking with the director before acting. The challenge for an actor in a project like this one is probably the reality that nothing is really straightforward, but rather pretty abstract.