Art World

Matthew Barney’s ‘River of Fundament’: An Egypto-Scatological Musical About Norman Mailer, Cars, and America

Up Matthew Barney's River of Fundament Without a Paddle

Up Matthew Barney's River of Fundament Without a Paddle

Benjamin Sutton

Matthew Barney needs an editor. This will hardly come as a surprise to devotees of his hours-long moving-image works like the Cremaster Cycle and Drawing Restraint series, art films with celebrity casts, blockbuster budgets and production values to match, set in distant locales and surreal, stylized alternate Americas steeped in seemingly ancient, stitched-together mythologies, which are celebrated in spectacular and inscrutable rituals that incorporate macho icons of US culture, from muscle cars, guns, football, and skyscrapers to Ernest Hemingway and Norman Mailer.

But for first-timers such as myself, this is a lesson learned the hard way during Barney’s latest, River of Fundament (2008–2014), which flows for a glacial five hours and 52 minutes, and from whose sewage-filled waters at least three excellent shorter films could be pulled. But I’m putting the carriage before the horse—or the smashed vintage Chrysler before the troupe of rope-tugging strongmen, to use the terminology of one of Fundament’s most mesmerizing sequences; first things first.

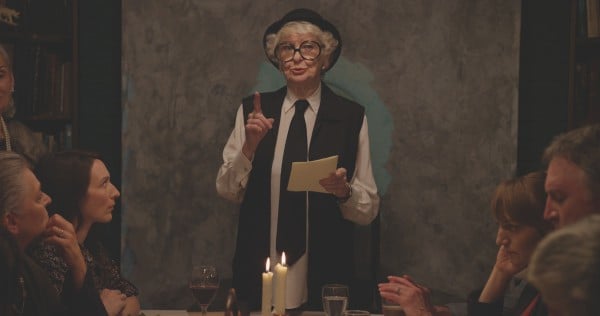

River of Fundament is a composite of five major plot strands and set pieces that flow into and across one another atop a flotsam of half-explored symbol systems, literary quotations, art historical allusions, pop culture borrowings, and formal motifs. The core sequence spliced throughout the film is a feast and wake in honor of Mailer held at his Brooklyn Heights home, where New York cultural figures from Lawrence Weiner and Elaine Stritch to Jonas Mekas, Salman Rushdie, and Fran Leibovitz come to pay their respects.

If that sounds straightforward enough, consider this: The elegant and curio-filled Mailer lair is actually a replica of the original set atop a barge and floating down the toxic creek that runs between Brooklyn and Queens. Still following? There’s more: The house’s sewage-flooded basement serves as a portal for ancient Egyptian pharaohs and various reincarnations of Mailer himself, whose quest to become immortal provides the film’s overarching narrative.

Production still from Matthew Barney’s River of Fundament.

Photo: David Regen. © Matthew Barney.

In a trio of elaborate set pieces based on performances Barney staged at a Los Angeles Chrysler dealership, an abandoned Detroit steel plant, and the Brooklyn Navy Yard in 2008, 2010, and 2013, respectively, Mailer’s spirit is successively reincarnated as a 1967 Chrysler, a 1979 Pontiac, and finally a 2001 Ford. This grafting of Egyptian death myths onto the contemporary American landscape—cultural, geographic, and psychic—is not as completely arbitrary as it sounds, and it’s the bizarre prism through which viewers are left to make some kind of sense of Fundament.

Layered atop the Mailer wake is a very loose adaptation of the author’s enigmatic 1983 historical epic-cum-fantasy novel Ancient Evenings. Characters from that unwieldy book about debaucherous, bloodthirsty Egyptian nobles and royals seeking to achieve immortality continually emerge from shit-strewn streams, whether it’s the bog in Mailer’s basement, New York’s toxic Newtown Creek, the Los Angeles River, or the Detroit River.

Production still from Matthew Barney’s River of Fundament.

Photo: Hugo Glendinning. © Matthew Barney.

The interactions between and among the wake attendees and ancient Egyptians—whose names are their only identifiably Egyptian features (the pharaoh Ptah-Nem-Hotep is played by Paul Giamatti)—make up Fundament’s most insufferable sections, with their stiff, self-serious dialogue and interminable volleys of guttural noises, yelps, and screams.

There are also moments of magic here, as when Stritch reads from Ancient Evenings to the rapt mourners, or when Ptah-Nem-Hotep gives a tour of his steampunk bathroom, whose plumbing leads directly to the flooded basement and its suspended hydroponic garden, about which he boasts: “My stool would cultivate the earth!”

The triumvirate of Mike Kelley, Paul McCarthy, and Barney has done an exceptional job of rubbing feces in our collective faces over the past year with the artists’ respective outputs—Kelley in several projects featured in his posthumous retrospective, McCarthy with his Hauser & Wirth and Park Avenue Armory installations and an inflatable dung pile in Hong Kong—but Barney takes the cake. Shit is undoubtedly Fundament’s dominant motif, analogy, generative material, and narrative by-product, but rebirth, regeneration, and transformation are at the center of its constellation of themes.

Production still from Matthew Barney’s River of Fundament.

Photo: © Matthew Barney.

“I’ve only watched this through six times . . . I hope it’s of interest,” he said by way of an introduction at the film’s world premiere at the Brooklyn Academy of Music on February 12. “I’m not going to tell you to enjoy it, because that’s not what it’s about.”

Perversely, though, there’s a great deal to be enjoyed in Fundament. The film is successful in many respects, from the three spectacular performances that anchor each of its acts and the stunning visuals—it’s no small feat to make a pile of cow innards reflected in a pool of raw sewage look like a Dutch still life—to the exquisite production, set, costume, and prop designs, and the avant-garde score by Jonathan Bepler. It looks like a major movie studio production. Shots of a golden Pontiac Firebird Trans Am flying along Detroit’s deserted streets could be taken from a forthcoming, ruin porn–themed Fast and Furious sequel. Where Fundament fails most egregiously as an artist’s version of a Hollywood blockbuster is in the script—in the cacophony of conversations, monologues, and songs that are meant to lend cohesion to its disparate and sprawling sections.

The film is bursting with portentous images, emphasized phrases, and possible readings. Barney highlights some of these recurring elements through repetition, musical cues, and other methods. There are numerous snakes in the film, for instance, often found cradled in car parts, or slithering around a room full of children, and at one point impregnating Isis (Aimee Mullins) in an operatic, CSI-like chapter starring a choir of FBI forensics squad detectives.

Characters in Old West costumes continually appear, from the spirits emerging out of the Mailer basement shit stream to the band performing before the film’s first car demolition—this is one of many, many commonalities between Barney’s work and that of David Lynch into which, one hopes, a film student somewhere is currently wading.

Production still from Matthew Barney’s River of Fundament.

Photo: © Matthew Barney.

But even more images and icons drift by unremarked-upon as the quasi-narrative lurches along: A guest at the wake melts metal into a tiny shovel that then dissolves in his drink; one of the fighters in a carnival-like brawl at the Brooklyn Navy Yard carries a small dog amid droves of hipster extras; a vulture perches on the flashing lights atop a Detroit Police Department cruiser while a squadron of steel worker percussionists stands beside it. Fundament is oozing with symbolism and potential interpretations, only a few of which Barney himself pursues.

Barney has a gift for visuals, but he’s no screenwriter, and this makes his need for an editor especially glaring. The often torturous conversations and musical face-offs taking place around the table at Mailer’s wake exacerbate Fundament’s self-serious tone, provide moments of unintended hilarity, and do little to untangle its complex web of narratives, which they needn’t do to begin with—this is an art film, not The Mummy 4. The incessant arguments over the fates of squabbling pharaohs about whom we could care less undercut the enormous tension Barney and Bepler manage to build in the film’s first act strictly through visuals and sound. Any interest in plot is beyond resuscitation by the final section, as Mailer’s wake turns orgiastic, and a council of gods and Hemingway lookalikes decides which pharaoh will become immortal.

A more engrossing version of Fundament might have jettisoned nearly all dialogue and consisted strictly of the film’s three major flashbacks—only identifiable as such thanks to Barney’s program notes—without the Mailer meta-narrative and Ancient Evenings adaptation clumsily connecting them. The LA Chrysler dealership funeral procession, with its posse of strongmen tugging a wreck in time to a cowboy musical ensemble; the Detroit steel mill smelt-athon; the West Side Story-esque Brooklyn Navy Yard dry dock brawl—each of these sequences articulates with incredible narrative economy and startling visual panache Barney’s dominant themes of decay, destruction, and quasi-alchemical transformation. But he drowns out his film’s strengths by flooding them with superfluous dialogue and shitty storytelling.

Production still from Matthew Barney’s River of Fundament.

Photo: Hugo Glendinning. © Matthew Barney.

Production still from Matthew Barney’s River of Fundament.

Photo: Hugo Glendinning. © Matthew Barney.

Production still from Matthew Barney’s River of Fundament.

Photo: Chris Winget. © Matthew Barney.

Production still from Matthew Barney’s River of Fundament.

Photo: Chris Winget. © Matthew Barney.

Production still from Matthew Barney’s River of Fundament.

Photo: © Matthew Barney.

Production still from Matthew Barney’s River of Fundament.

Photo: © Matthew Barney.

Production still from Matthew Barney’s River of Fundament.

Photo: Hugo Glendinning. © Matthew Barney.

Production still from Matthew Barney’s River of Fundament.

Photo: Hugo Glendinning. © Matthew Barney.