A court in Paris has dismissed a claim by French sculptor Daniel Druet demanding to be recognized as the creator of nine wax figures he was commissioned to make for the Italian conceptual artist Maurizio Cattelan.

But there is disagreement about whether the ruling still leaves the key question of the case in doubt: whether a fabricator can rightfully claim authorship of an artwork made on commission for an artist.

On July 8, judges electronically announced their decision in the closely followed case, which saw French lawyers debate the meaning of conceptual art and the recognition of assistants who contribute to artworks under the direction of a single author.

“The question of authorship—even the validity—of art … is at the heart of this dispute,” a group of more than 60 art workers including Annette Messager, Sophie Calle, and Chris Dercon wrote in an editorial supporting Cattelan published in Le Monde in May.

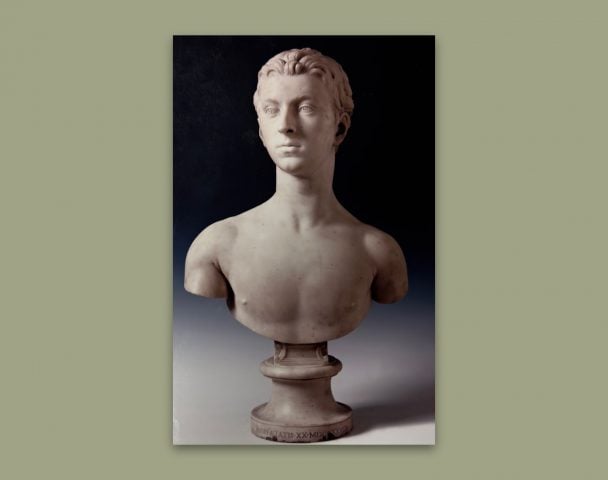

The 80-year-old Druet said he was never rightly named creator of some of Cattelan’s most famous works, made between 1999 and 2006, and for which both parties recognized he was paid. He sought nearly €5 million ($5.25 million) in compensation. Among the sculptures he created was a wax model of the Pope crushed by a meteorite, in Nona Ora.

But the Paris intellectual property court ruled that Druet’s claim was “inadmissible” because he never directly sued Cattelan himself, only the Italian artist’s gallery, Perrotin, and the museum Monnaie de Paris, which showed Cattelan’s works from 2016 to 2017. Druet was also ordered to pay €10,000 to Galerie Emmanuel Perrotin and the Monnaie de Paris.

“It is with immense satisfaction that I learn of this decision, which enshrines the work of Maurizio Cattelan as a conceptual artist and rejects in every respect the inadmissible and unfounded arguments of Daniel Druet. I am delighted that this decision puts an end to this controversy which has threatened a large number of contemporary artists,” Emmanuel Perrotin said in a statement.

In addition to their dismissal of Druet’s request, judges also affirmed that the installation and scenography of the wax models in question “came from [Cattelan] only, Daniel Druet being in no position… to take the slightest part in the choices relating to the scenic setting of the said effigies” nor “the content of the possible message to be conveyed through this staging.” This observation—which is uncontested by both sides—means Druet cannot be named sole author of the completed artworks, which necessarily include their conceptual installation by Cattelan.

Seizing upon that opinion, Galerie Perrotin said that “this decision constitutes groundbreaking case law, as for the first time, magistrates enshrine conceptual art in a landmark ruling.”

“Beyond this court decision, it is conceptual art that is now protected by the rule of law,” added the lawyers for the gallery, Pierre-Yves Gautier and Pierre-Olivier Sur.

Yet Druet’s lawyer, Jean-Baptiste Bourgeois, told Artnet News that by rejecting Druet’s lawsuit for sidestepping Cattelan, rather than suing him so he could defend himself, the court never addressed the central question of authorship in their ruling.

“I’m disappointed by this judgment, which I find disputable on several levels. The judges have pushed aside the debate, citing arguments that are unfounded,” Bourgeois told Artnet News over the phone. Indeed, the same intellectual property court, led by different judges, had earlier ruled in February 2000 that Druet’s claim was legally admissible.

The judges “didn’t even open the file” and accepted the counter argument that since “[we] didn’t summon Cattelan, everything [we’re] asking for goes to the trash,” Bourgeois said. “We haven’t moved forward on the debate itself.”

As for the court’s opinion that Druet’s had no role in the dramatic installation of the wax sculptures, Bourgeois insisted his client never claimed to have authored those works in their entirety. Rather, he said, Druet believes he is only the author of one component—the wax models—used within the conceptual artworks by Cattelan.

“We aren’t claiming Daniel Druet told Cattelan that the little Hitler [from the work Him] should be placed or positioned in any particular fashion… that is not at all Druet’s concern,” Bourgeois said. Claims to the contrary, added the lawyer, were “lies.”

However, in an attempt to clarify apparent confusion over what Druet is asking for in the first place, judges noted that while Druet did “not contest” his lack of involvement in the installation of the works, it “must be understood” he wants to be named “exclusive” author of the nine works as shown in their entirety, effectively denying any role that Cattelan had in their making at any stage.

“Once [Druet] does not precisely limit his demand for rights to the wax effigies only … but designates them by the name with which these works were unveiled, without any other specification, it must be understood that M. Druet is soliciting authorship of the works as they are revealed to the public, i.e. according to a certain installation,” stated the judges.

In an editorial published on July 11, the editor-in-chief of the French-language Art Newspaper, Philippe Régnier, wrote: “The least we can say, is that [the judge’s ruling on July 8] doesn’t settle anything, because it dismissed the claimant for the motive that he did not include Maurizio Cattelan in the case … This decision could lead to a new claim directly implicating the Italian artist. Thus, this serial drama is still far from having revealed its outcome.”