Art World

In Pre-Industrial Europe, Blue Pigments Were Exceedingly Rare. But an Ocean Away, the Maya Had Their Own, Widely Available Blue

Maya Blue was used for centuries in present-day Mexico.

Maya Blue was used for centuries in present-day Mexico.

Sarah Cascone

In Europe, before the Industrial Revolution and the invention of synthetic blue paints, artists used blue pigment—which was at times more expensive than gold—exceedingly rarely.

Thanks to the high cost of the semi-precious lapis lazuli stones imported from far-off Afghanistan, blue was precious and scarce.

Across the ocean, it was a different story.

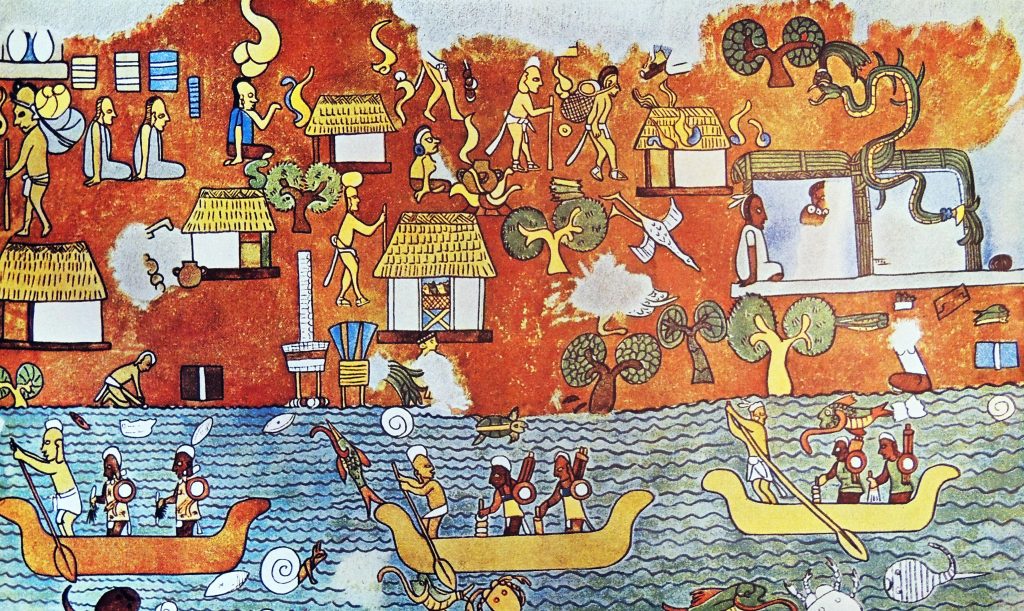

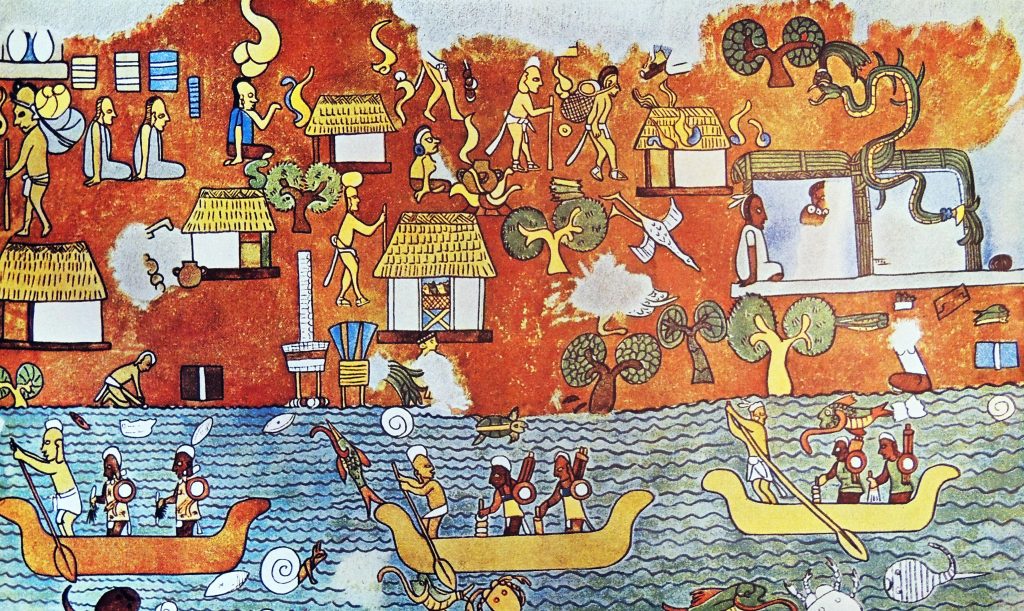

There is evidence of the Mayans using their own blue—Maya Blue—possibly as early as 600 BC, and it can be found in the ancient city of Chichén Itzá.

The pigment’s heyday was in the 8th century, when it was widely used to paint murals of the classical Maya period.

Art historians and scientists alike were baffled as to the origins of the vibrant blue in Maya art until the 1960s, when the source of this brilliantly hued pigment was finally identified: it was made by mixing a rare clay (called attapulgite or palygorskite) with the dye from the añil plant, part of the indigo family.

The paint made from this ancient superblue is long-lasting, resistant to abrasion, sunlight, and high temperatures.

One of the Mexican lacquer pieces in the Hispanic Society collection includes this Periban lacquer batea (circa 1650). Photo courtesy of the Hispanic Society of America, New York.

“Maya Blue is an example of the technological refinement of indigenous civilizations and of the investment they made in artistic production,” said Davide Domenici, a professor of history, cultures, and civilization at the University of Bologna, told Artnet New in an email.

The complex method of producing the pigment is “still poorly understood,” according to Domenici, but involved boiling the indigo with the fibrous palygorskite to bond the two together molecularly, rather than just dying the exterior the of the clay. Because the clay is nano tubular, Domenici explained, intercalating the indigo within that structure creates a very durable pigment.

This virtually unsung achievement is all the more remarkable when one considers that even today, creating new stable blue pigments remains a challenge. (In 2009, chemist Mas Subramanian accidentally created the first new blue pigment in 200 years.)

Nevertheless, there still historically hasn’t been much research into Maya Blue.

“When I first started working as a conservator, nobody was looking at this stuff,” Monica Katz, an objects conservator at the Hispanic Society of America in New York, told Artnet News.

“The big museums have collections of European painting and that’s where the research was done.” But in the past five years, she said, “there has been a lot of research on Maya Blue.”

To date, the Hispanic Society only knows of a handful of works in their holdings that feature Maya Blue, in Mexican lacquer works from the 1650s to the 18th century, likely made by Indigenous artists influenced by a European aesthetic.

“You have to do invasive testing to identify Maya Blue, because it doesn’t have any heavy metals,” Katz said.

In 2018, a high-profile show of colonial Mexican painting, “Painted in Mexico,” organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Fomento Cultural Banamex in Mexico City, came to the Metropolitan Museum Art in New York.

Soon after, a BBC article suggested that Baroque artists in Mexico might have added Maya Blue to their palettes upon arriving in the New World.

Baltasar de Echave Ibia, The Immaculate Conception. Painting in Mexico, the artist had access to Maya Blue, allowing him to use a color that was prohibitively expensive in Europe. Courtesy of the Museo Nacional de Arte de Mexico.

It’s true that artists such as José Juárez (1617–1662), Cristóbal de Villalpando (1649–1714), and Baltasar de Echave Ibia (1583/84–1644)—known as “El Echave de los azules,” Spanish for “Echave of the blues”—could almost certainly not have afforded precious ultramarine, and its use was not recorded in New Spain.

“As far as I know, the use of Maya Blue by European colonial artists has never been confirmed by chemical analyses,” said Domenici. “Azurite (a mineral, much easier to use), for example, was commonly employed in colonial Mexico.”

That might be a likelier source of the bold blue used prominently in, Echave’s painting The Immaculate Conception.

Elsa Arroyo, a researcher at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, agrees that it’s unlikely works like this use Maya Blue.

“Maya Blue has very good properties when it’s mixed with tempera or gum, or when it’s being used in fresco technique, or what is called a–secco,” she told Artnet News in an email. “But Maya Blue cannot match the celestial blue color of indigo when mixed with lead white in oil paintings.”

The pigment has a similar refraction index as the common binder linseed oil, making it difficult to create a solid paint coating, and the yellow tint of the oil also alters the hue of Maya Blue, which already verges on turquoise.

So while Maya Blue doesn’t appear to have caught on among colonial artists, indigo, another local color, did.

“After the Spanish conquest, añil plants from Mexico entered on the list of the precious materials worth of exploitation and exportation to Europe,” Arroyo said. “Indigo was widely employed since the last third of 16th century in artworks from European masters established in Mexico City.”