Reviews

M.C. Escher Is the King of Trippy Optical Illusions, But He Deserves More Credit Than That

"Escher-mania" hits Brooklyn's Industry City.

"Escher-mania" hits Brooklyn's Industry City.

Ben Davis

M.C. Escher (1898–1972), an artist of enigmas, has this larger enigma about him: He is inexplicably overrated or inexplicably underappreciated, depending on how you look at him. Like one of his optical illusions, both seem to be true at once.

He is the exact contemporary of both René Magritte (1898–1967) and Norman Rockwell (1894–1978). But while he shares an eye for icy paradoxes with the Surrealist, reputation-wise, he is placed closer to the illustrator. The man whose full name was Maurits Cornelis Escher does not, generally, feature in art history textbooks. Yet ask a random person to name a famous 20th-century artist, and as likely as not, you’ll get M.C. Escher.

“Escher: The Exhibition and Experience,” a crowd-courting touring pop-up show touching down at the slick high-end pleasure park that is the new Industry City, doesn’t actually set out to correct that disconnect. It runs with it.

Installation view of “ESCHER. The Exhibition & Experience” at Industry City. Photo by Adam Reich. Courtesy of Arthemisia.

Produced by Arthemisia, a private events production company from Italy, “Escher” boasts of being “the most important and the largest exhibition of M.C. Escher ever presented in the United States,” with more than 200 of the Dutch artist’s highly imaginative lithographs and woodcuts.

The opening galleries of the show survey Escher’s early experiments, to illuminating effect. To give a sense of his influences, it includes a sample of the Art Nouveau graphics by his mentor, Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita (1868–1944). In Escher’s dramatic early prints on religious themes (The Second Day of Creation, Tower of Babel) you see his eye for vertiginous perspectives. In his illustrations for a book of Dutch proverbs (“Emblematica”), you see his knack for dreaming up resonant symbols.

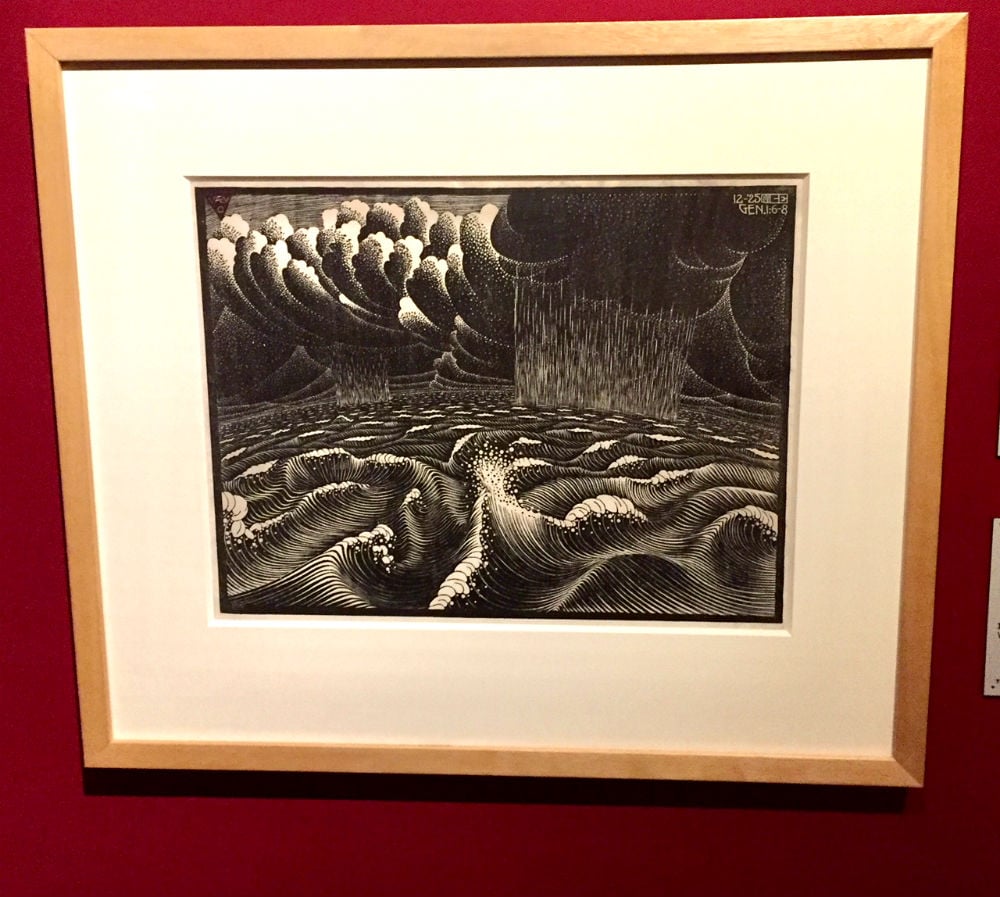

An early work by M.C. Escher, The Second Day of Creation (The Division of the Waters) (1925). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Still, the Escher of the 1920s and ’30s is pretty conventional and surprisingly naturalistic. For a long stretch, his main preoccupations are images capturing the geometric majesty of churches and the quaint drama of Italian landscapes.

After this prelude, the show arrives at Escher’s most famous phase—and thereafter, it basically loses any real personal throughline, shifting into thematic clusters of his works (“Tesselation,” “Structure of Space,” “Geometric Paradoxes”). These are liberally interspersed with what can only be described as loosely Escher-themed carnival attractions.

Installation view, “Escher: The Exhibition & Experience” at Industry City, June 8, 2018 – February 3, 2019. Photo by Adam Reich. Courtesy Arthemisia.

And so, you can look forward to taking a photo in an “Infinity Room”-style mirrored chamber, amid strings of repeating shapes; a “Relativity Room” where trick perspective makes you appear huge or small, depending on where you stand; an interactive video station where you can take a photo of yourself projected inside an Escher image; and more besides that. There are also science museum-style wall displays, instructing visitors on the basics of certain optical illusions, giving the whole thing the feeling of a children’s museum.

Strangely, in its way, this sliding in emphasis from “Escher: The Exhibition” to “Escher: The Experience” replays the very history of M.C. Escher’s reception, the artistic trajectory that has given him his unresolved reputation in the first place.

Visitors take photos in the “Relativity Room” in “Escher: The Exhibition & Experience.” Image courtesy Ben Davis.

For more than a decade up until the mid-1930s, Escher lived in Rome. But fascism was ascendant, and when his young son began to associate with a fascist youth league in school, he decided to move his family. The show notes that his interest in tiled patterns was inspired by the intricate all-over Islamic geometries of the Alhambra in Spain. But it’s worth adding that just a month after Escher’s final visit to Granada, in June 1936, the Spanish Civil War erupted—the blood-soaked opening skirmish of World War II.

Having dodged Italian fascism, Escher eventually returned to his native Holland—which was to be occupied by the Nazis in 1940. De Mesquita, his friend and mentor, was Jewish. He was rounded up, to perish in Auschwitz, his family “carried away like cattle to be butchered,” as Escher remembered later. He recalled finding an artwork literally stamped with a boot print in de Mesquita’s wrecked home, and would later labor to ensure that his teacher’s legacy was not forgotten.

Escher was not a man of outspoken political convictions, and yet the world depicted so vividly in his earlier works was indelibly upset by politics. The mutation of his work from observations of the real world toward elegantly imagined paradox, fully accomplished by 1938, tightly corresponds to his actual retreat from Rome. He insisted he was simply less interested in landscapes outside of Italy. In some way, the turn towards fascinating unreality seems a way to cope with messy reality.

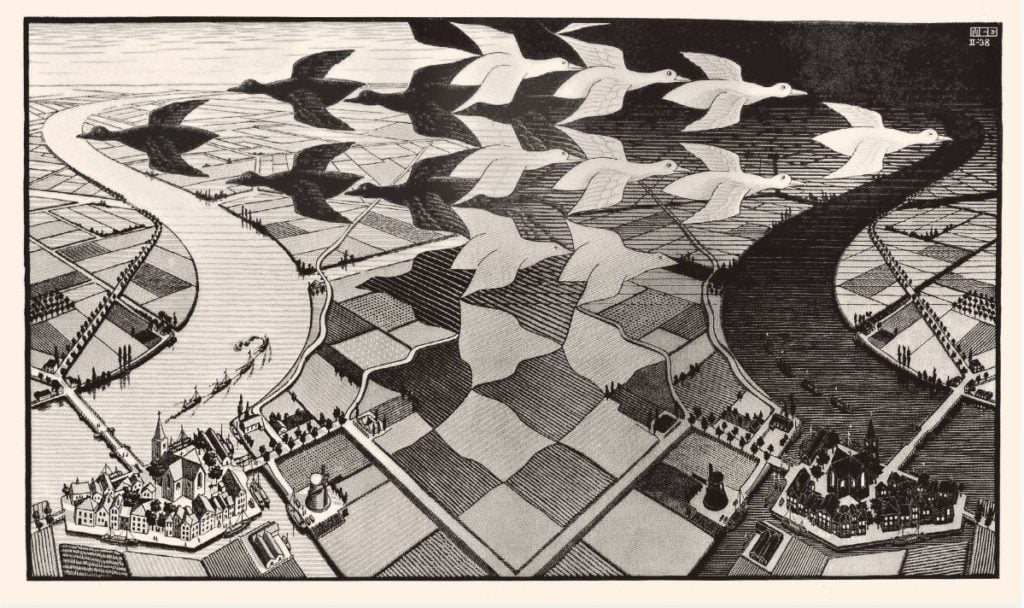

M.C. Escher, Day and Night (1938). Private Collection, USA. @ 2018 The

M.C. Escher Company. All rights reserved www.mcescher.com

Day and Night is credited as the first image of Escher’s classic style. It also figures this transition: a sweeping aerial vista of farmland, mirrored symmetrically, with one half rendered as if seen in darkness, the other half as if seen in the daylight. Square plots of farmland seem to morph into birds in flight passing between the two. The world, realistically observed as in his earlier landscapes, now bends into a world that can exist only in the mind, or on paper.

Escher was on the edge of 40 when he made this new course. But he did not really get his big break until he was in his mid-50s, well after the war’s end, when the Stedelijk Museum organized a solo show opposite the International Mathematics Conference, in 1954. It was mathematicians who first really embraced Escher, with several becoming collectors and correspondents.

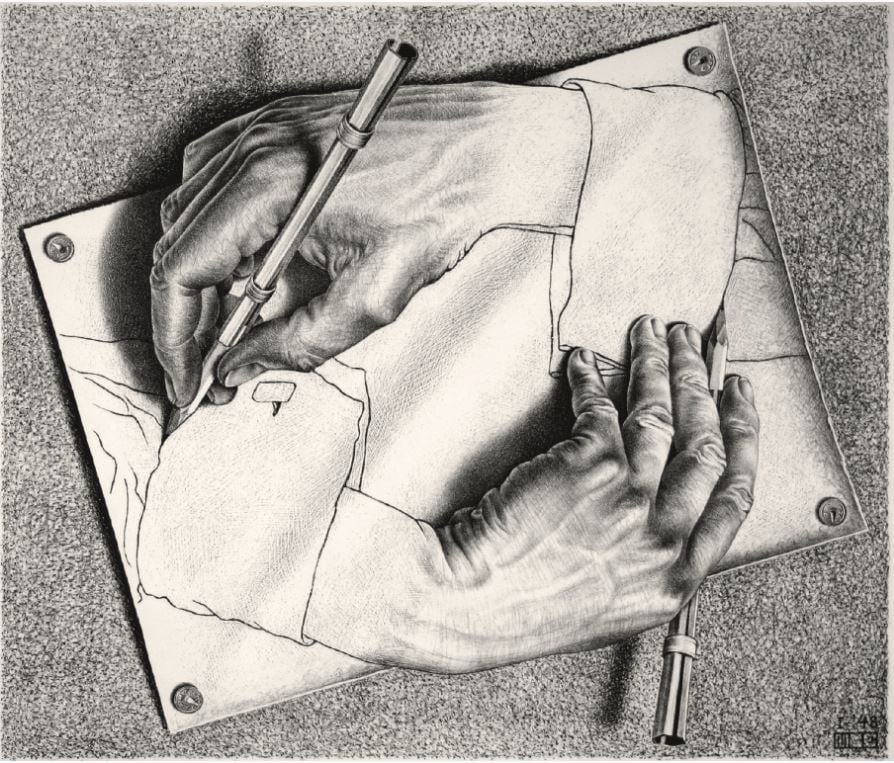

M.C. Escher, Drawing Hands (1948). Lithograph. Private Collection, USA. All M.C. Escher Works @ 2018 The M.C. Escher Company.

Some of those professors brought the works back to adorn their offices in the US and elsewhere. In the show catalogue, Escher expert Federico Giudiceandrea argues that it was through that route, not the world of art, that young students discovered M.C. Escher in the 1960s, and that his influence, little by little, seeped into the larger culture, becoming ubiquitous on book covers and calendars.

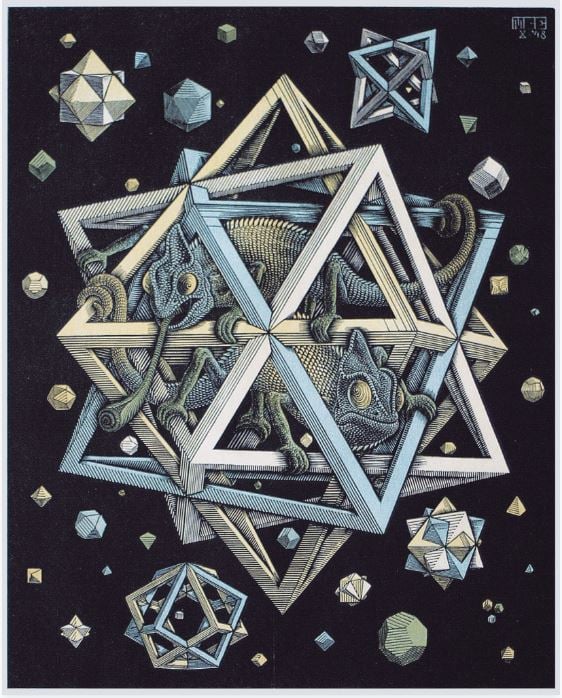

M.C. Escher, Stars (1948). Private Collection, USA. @ 2018 The M.C. Escher Company.

Like J.R.R. Tolkein, M.C. Escher’s work achieved a vast new exposure via the hippies. Also like Tolkein, Escher didn’t always appreciate or understand his ardent new fans. And while Tolkein was trying to prevent the Beatles from making a version of Lord of the Rings starring the Fab Four, Escher was coolly turning down Mick Jagger, who wanted an Escher illusion for the cover of Let It Bleed. (The serious Dutchman did not appreciate the informal tone of Jagger’s letter of solicitation, concluding a curt reply with the line, “By the way, please tell Mr. Jagger I am not Maurits to him, but / Very sincerely, M.C. Escher.”)

A vast market in bootleg Escher sprung up in the ‘60s, leading the artist to found the M.C. Escher Foundation in 1968 to try to rein in what he considered bad interpretations of his work. An early image, Dream (1935), showing a giant praying mantis alit atop a sarcophagus, was circulated in the States as a dorm room poster titled Bad Trip.

Selection of black light posters in “Escher: The Exhibition & Experience” (with Bad Trip at the left). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Most amusingly, according to Giudiceandrea, Reptiles (1943)—a still-life depicting a drawing of little dragon-like creatures coming to life—was gleefully adopted as an icon of drug culture. The inclusion of rolling papers on the tabletop, and the little lizard snorting smoke led it to be read as a marijuana tribute, à la “Puff the Magic Dragon.” (Escher did not, as far as we know, partake.)

As mathematical illustration and groovy allegory—this is how M.C. Escher found fame and is why he retains this odd outsider status. While making note of his misappropriation, this strange show also revels in “Escher-mania,” as one gallery is titled. It even features a chamber full of unauthorized black-light posters inspired by him.

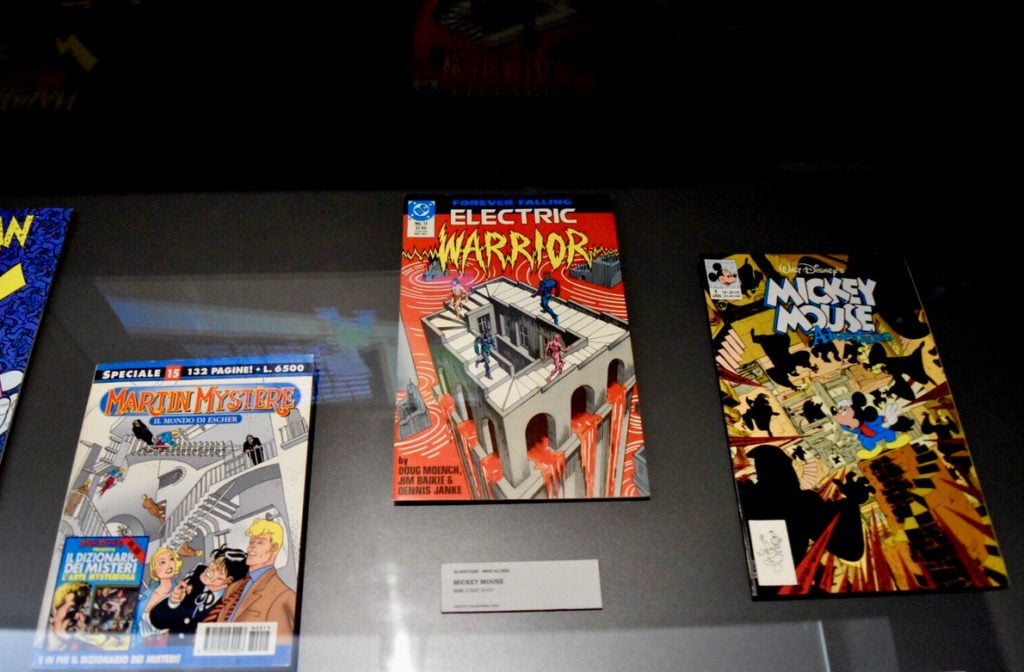

Selection of comic book covers inspired by M.C. Escher in “Escher: The Exhibition & Experience.” Image courtesy Ben Davis.

And yet, what revisiting the ample selection of works here makes me think is that M.C. Escher deserves a little more consideration as an artist than he gets.

It’s worth stressing that what makes his images stick is not just that they show optical illusions or clever paradoxes—though they do that, clearly. He was no mathematician, though he enjoyed his correspondence with mathematicians. What Escher did was give to the popular interest in illusion and paradox a distinctive symbolic vocabulary.

The storybook God’s-eye perspective in his worlds channel the likes of Pieter Bruegel the Elder and, above all, the jovial late-medieval nightmare of Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights. (In November 1935, just after leaving Italy, he produced a print titled “Hell”, copy after Hieronymus Bosch.)

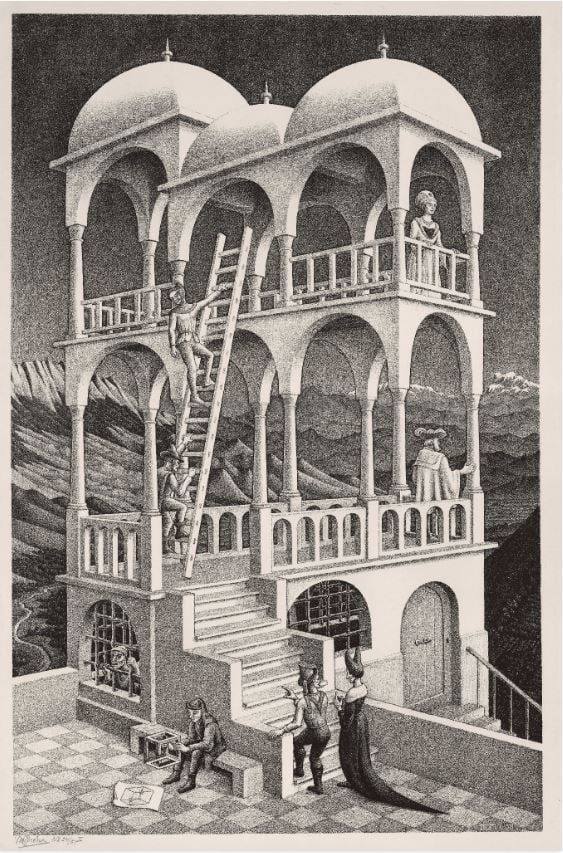

M.C. Escher, Belvedere (1958). Private Collection, USA

All M.C. Escher Works @ 2018 The M.C. Escher Company. All rights

reserved www.mcescher.com.

If I think back to my first childhood exposure to Escher’s work, the images stuck in my brain not because of their cleverness, but because of the inscrutable creepiness of works like Flatworms (1959), with its googly-eyed creatures slithering over an impossible architecture, or House of Stairs (1951), with its armored worms (“Wentelteefje,” a creation of Escher’s) parading from one logic-bending platform to the next.

“El sueño de la razón produce monstruos,” Francisco Goya scrawled on a famous 1799 etching, an image of a dreamer swarmed by birds and owls that represent the darker side of the Enlightenment-era imagination: “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters.” Escher is nowhere near as hard-hitting as Goya—he is out to delight with illusion, not to warn with evil visions—but the imagery unleashed through his fantasies is quite deliberately alien.

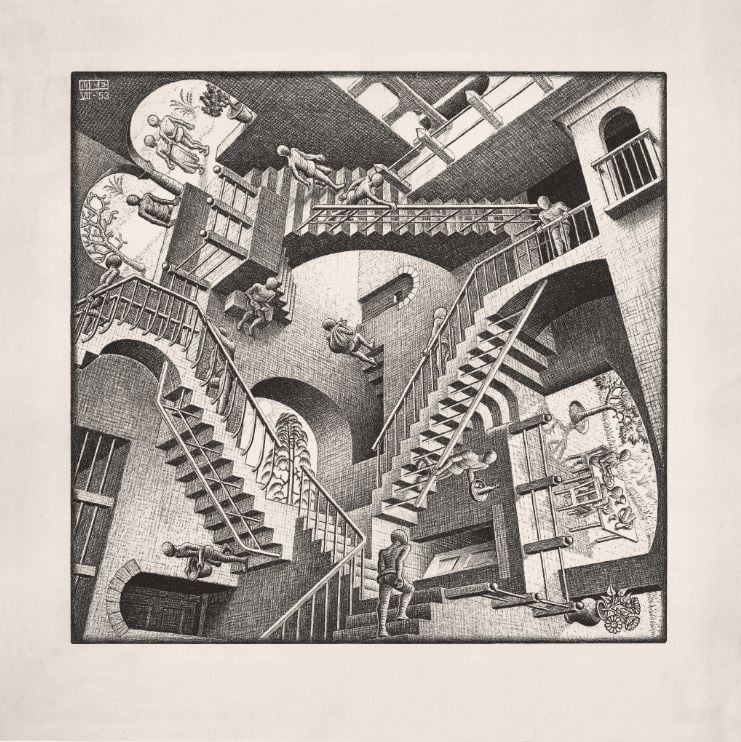

M.C. Escher, Relativity. Private Collection, USA. @ 2018 The M.C. Escher Company.

Escher’s work is often branded as cold and emotionless. I think you can read this as being somewhat self-conscious. They are allegories of circling thoughts that can’t find a way to touch down in the warmth of lived reality, which his why his symbolism is so insistently otherworldly.

One can distill Escher-ism down to “groovy illusion”—that is, after all, the basis of the “experience” part of this “Exhibition and Experience.” But I don’t think you do justice to what actually made the work stick without noting that his imagery carries a symbolic charge within its pokerfaced paradoxes. It’s no coincidence that when Escher’s visions are evoked in pop culture—the show ends with film clips from Labyrinth, Night at the Museum, and Inception—it is almost always as an image of being trapped, imprisoned by inscrutable forces.

Installation view, “Escher: The Exhibition & Experience” at Industry City, June 8, 2018 – February 3, 2019. Photo by Adam Reich. Courtesy Arthemisia.

If Goya’s etchings depicted the hell unleashed by reason’s absence, you could say that Escher depicted the purgatory of reason that has retreated into itself. On this level, to turn him into a fun park does fail him. I suppose you can appreciate M.C. Escher both as an artist and a phenomenon—but you definitely have to see both aspects to get the full effect.

“Escher: The Exhibition & Experience” is on view in Industry City, 34 34th Street, Building 6, Brooklyn, New York, through February 3, 2019. Hours: Monday–Wednesday and Friday–Sunday from 10:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m; Thursday from 10:00 a.m. to 9:00 p.m.