As conversations about bias in health care reach new heights amid the COVID-19 pandemic, a new course at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine is hoping to combat the scourge with an unlikely tool: famous artworks.

The school has launched a new course in collaboration with the university’s Abroms-Engel Institute for Visual Arts and the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute that tasks junior- and senior-level med students with analyzing works of art by figures including Michelangelo, Paul van Somer, and Sir Luke Fildes. The goal is to teach them to look before they jump to conclusions, becoming mindful of assumptions they make based on race, class, or previous knowledge.

“Art gives the majority of medical students something that is outside of their personal and perhaps cultural educational experience… and allows them to learn strategies for observation in something that is familiar, which is the clinical exam room,” Stephen Russell, an associate professor of internal medicine and pediatrics who developed the course, tells Artnet News.

“In those settings, they’re so used to trying to get at the diagnosis that they forget that what we really want is just description,” he adds.

Mary Cassatt, Girl in the Garden (1880-82). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

What might this philosophy look like in practice? Russell points to Mary Cassatt’s Girl in the Garden (1880–82), a portrait of a woman sewing in a verdant landscape. “Cassatt simply painted what she saw and she was a really acute and accurate observer,” he says. As it turns out, she painted a woman who, Russell says, had rheumatoid arthritis.

“While Mary Cassatt probably didn’t know much about rheumatoid arthritis, in that particular picture she painted someone who we can, from a distance of 140 years, tell had that,” he says.

“Prescribing Art: How Observation Enhances Medicine” is an updated version of a previous course first launched by Russell at the university in 2011.

While the original class (which was itself based on a seminar created at Yale) also sought to improve students’ observation skills through artistic analysis, this year’s version was expanded to focus specifically on biases and what Russell calls the “tolerance of ambiguity.”

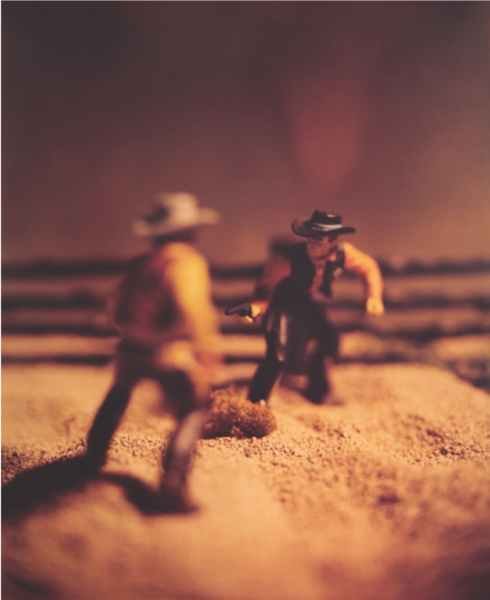

David Levinthal, Untitled (1989), from the series “Wild West.” Collection of the Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts, UAB.

A 1989 “Wild West” picture by photographer David Levinthal, which depicts miniature toy cowboys in a cinematic shootout, generated numerous assumptions from the students, says Russell—the roles of the two gun-wielding figures, the setting of the scene. The biggest takeaway, though, wasn’t what the photo told them; it was its sense of irresolvability and the mystery of Levinthal’s intention. The picture can help doctors internalize the fact that some things are impossible to determine conclusively.

“Because in the midst of COVID-19, there’s so much that we want to know but so much that we don’t know,” Russell explains. “The pandemic has taught us that you have to move forward when the answer is not fully known.”

The class recently wrapped up its first term, which was conducted over Zoom, and will be held again in the fall semester.