Archaeology & History

Unassuming Slab Is Identified as Long Lost Medieval Altar

A stone slab in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem is more than it seemed.

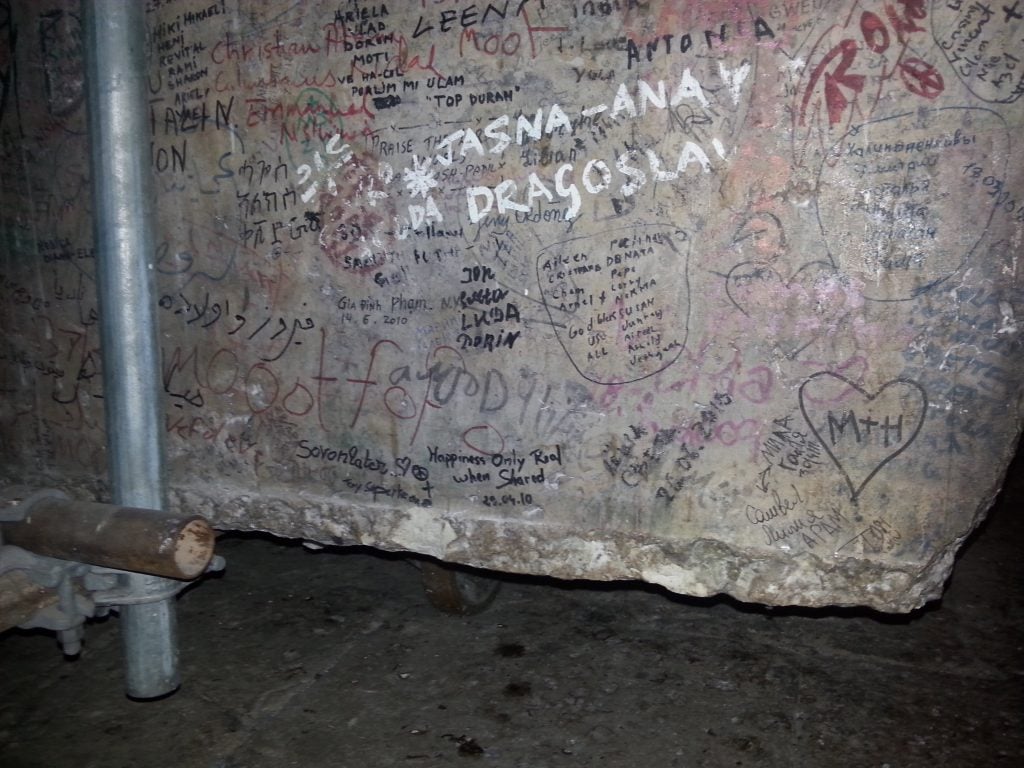

For ages, a massive stone slab sat in a rear corridor of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. It appeared an unassuming artifact; over the years, tourists had even left graffiti on its surface. But recent construction work necessitated moving the block and turning it around, leading to an astonishing discovery that brings its deep heritage to light.

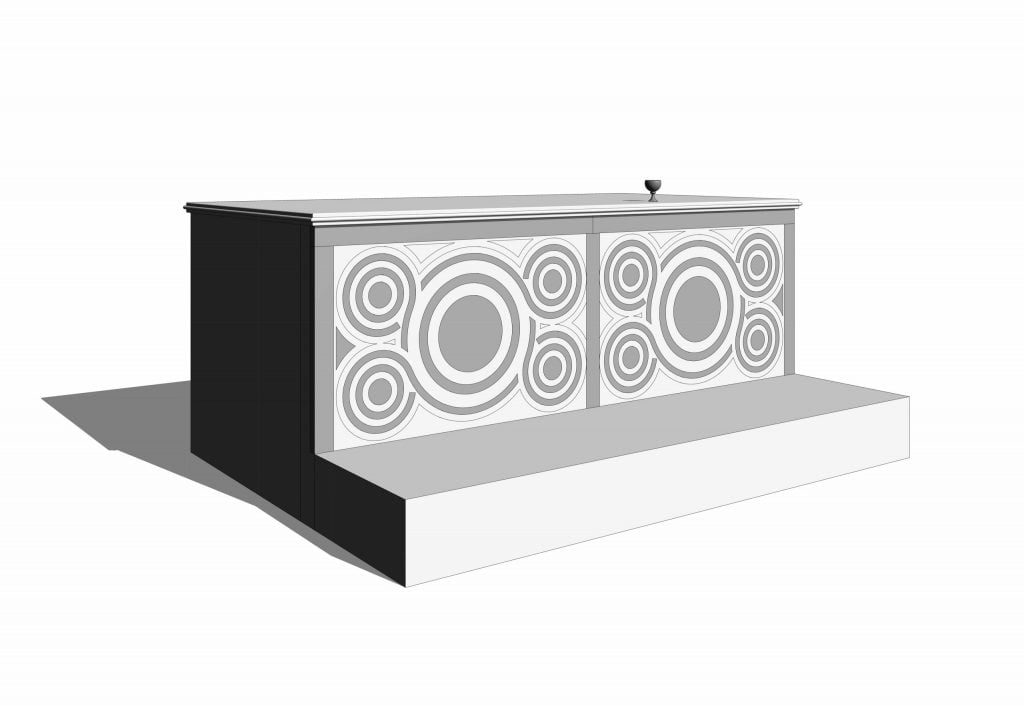

Once flipped over, the front of the eight-by-five-foot slab revealed geometric patterning, featuring five circles formed by an unbroken band, a spiritual symbol known as the quincunx. Based on the motif, archaeologists from the Israel Antiquities Authority and the Austrian Academy of Sciences (OeAW) have identified the hunk of stone as part of a once-elaborate Medieval altar, consecrated in the 12th century and long thought lost.

The front panel of the Crusader high altar as it looks today. Photo: Shai Halevi. © Israel Antiquities Authority.

Built in 326 C.E. at the behest of Roman emperor Constantine, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was long considered a sacred site by Christians. The building, it was believed, sits on the location where Jesus was crucified, entombed, and rose from the dead—hence the church’s name, which refers to either the resurrection or Jesus’s empty tomb.

In 1149, the European Crusaders, recognizing the church’s significance, re-consecrated it after conquering the Holy City and installed a new high altar.

The back of the altar. Photographer: Amit Re’em. © Israel Antiquities Authority.

The marble altar was reportedly an imposing and beautiful piece of work, adorned with unusual carvings by stonemasons. It was so impressive that pilgrims in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries were still singing its praises in extant accounts, said Ilya Berkovich, a historian at OeAW.

In 1808, a fire ravaged a part of the church. “Since then, the Crusaders’ altar was lost,” Berkovich said in a statement. “At least that’s what people thought for a long time.”

While the slab is a momentous discovery in itself, the stone’s decorations have also unearthed a surprising historical connection. The patterning on the block was created in a style known as Cosmatesque, characterized by geometric stonework and decorative inlay using marble. The technique was exclusively practiced by guild masters in Rome around the 12th century; their intricate work can be found in numerous churches, such as the San Crisogono, the Sistine Chapel, and the Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican.

Preliminary digital reconstruction of the Crusader high altar. Design Roy Elbag. © Ilya Berkovich/Amit Re’em.

Cosmatesque art was such a cherished form that it is rarely found outside Rome—in fact, only one example has been identified, in Westminster Abbey in London, to which the Pope had dispatched a guild master, according to OeAW. The team posits that the altar in Jerusalem was likely created by one of these Cosmatesque masters, who was sent with the Pope’s blessing.

Berkovich believes that the papal archives might hold further details about the altar’s history and even the identity of the master who crafted it. But for now, the connection between Rome and Jerusalem appears apparent.

“The Pope paid tribute to the holiest church in Christianity,” he said.