Artists

Artist Meghann Stephenson Sends an Elegant World Crashing Down

In her New York solo debut, "Swan Dive," the painter's sophisticated vignettes are on the cusp of calamity.

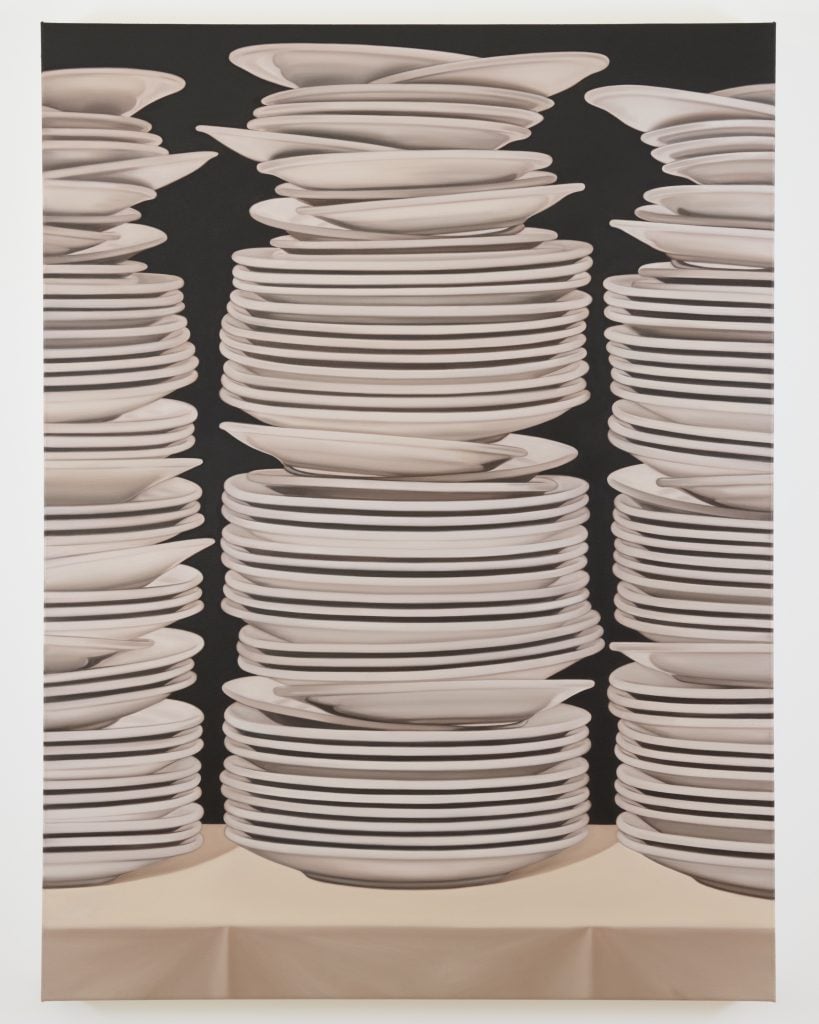

“Who gets to self-destruct and is it always a bad thing?” asked artist Meghann Stephenson as we walked through her New York solo debut “Swan Dive” at Half Gallery’s Annex Space. The jewel box of a show features eight new oil-on-canvas works of isolated vignettes—a stack of white dinner plates slightly toppled, a hand snipping a white tulip with a pair of scissors—each set against a spare black background.

Meghann Stephenson, Everything You Ever Wanted (2024). Courtesy of the artist and Half Gallery.

The show is on view through December 21. Self-destruction isn’t screamed in Stephenson’s beautiful, highly exacting images—it’s whispered. The artist, who is 34 and based in Los Angeles, was sharply dressed in boots and a floor-length trench when we met on a rainy afternoon. She seemed, consummately composed, an unlikely harbinger of upheaval chaos—which is part of the point.

“Women face a lot of societal pressures for perfection and self-sacrifice,” Stephenson shared. “It can feel like a pigeonhole because there is such a narrow, acceptable path. Maybe self-destruction has a bit of appeal, in that case. Maybe that’s the route to agency?”

Stephenson’s clues to discord are subtle. In one painting, Delicate (2024) which is displayed in the gallery’s storefront window, two martinis, alluringly frosty with condensation, are positioned precariously on the edge of a white linen table, ready to topple at any moment. Looking at the work, I formed a narrative in my mind: a couple, out to dinner, and the suddenly icy moment when an evening can quickly unravel.

Meghann X, It Was Mine First (2024). Courtesy of the artist and Half Gallery.

Stephenson acknowledges that the dynamics of feelings in relationships are a recurrent consideration in these works. “Every painting starts with a personal feeling, then I try to find the most accurate and subtle way to depict that feeling visually,” she explained. “My goal is always for the viewer to relate to that feeling and recognize it as though it’s something on the tip of their tongue.”

On one side of the gallery, five paintings of the same size hang together, forming the central narrative arc of the exhibition. These works feature hands from unseen figures and a few symbolic objects against black backgrounds. In one painting, Bite the Hand, an arm extends holding a silver platter with a crumb of bread on it. In another, The Nerve, we see a woman in a Jackie Kennedy-esque pink dress, with the tag still on it, from behind. The woman is crossing her fingers behind her back. It’s a mysterious image and we’re left wondering what the woman is hoping for… maybe to get away with a small act of shoplifting or, emerging from a dressing room, she’s hoping someone buys her the dress.

Meghann Stephenson, Swan Dive (2024). Courtesy of the artist and Half Gallery.

“Hands offer a bit of intimacy, but also nod to the transactional nature of relationships,” Stephenson explained. In these images, she used her own hands, as well as her husband’s, as models. She’s refined this spare, elegant visual language over the past several years. The artist, who was born in Virginia, earned her B.F.A. at Pratt in 2013. In recent years, her work has been included in group shows at Woaw Gallery, Hong Kong; Moosey, London; Harper’s, East Hampton and Half Gallery, which presented her works at the Armory Show. “Swan Dive” however offers a major moment of introduction for the artist. “You can see the devolving of a relationship and the main character coming into more agency,” she said of the arc of the show.

Her works, while pithy, conjure up a wide range of influences. “I have a very strong reverence for historical works, and that’s where I draw a lot of inspiration and motivation,” she added. Her paintings seem to take place outside of time—the objects that occupy her world are not easy to pinpoint to an era. “There’s a lot of power in objects. We all have some relationship to them,” she said “I want there to be timeless quality to everything, but still have something maybe modern about the narrative.” At the same time, Stephenson’s works often hide easter-egg details, which hint at Dutch Golden Era paintings. In the recent work, The End, a hand grasps a broken string of pearls, against a backdrop of black fabric. The pearls in the image spell out “the end” in Morse Code. In certain works, Italian artist Domenico Noli’s cropped-in attention to detail and fashion seems a reference as are Anna Weyant’s paintings, with their theatrically darkened backgrounds. Unexpectedly, Francisco de Zurbarán, the 17th-century Spanish painter, famed for his spare and dramatic Baroque scenes, also came to mind when considering her compositions.

In the exhibition’s titular painting, Swan Dive, a pristinely white swan drives itself downwards headfirst, its wings outstretched, against a backdrop of black. A glint of determination can be seen in the bird’s eye. The image is the visualization of a swan dive (when a swan plunges head-first into a body of water). It’s a term that has also become a colloquialism for self-destruction. Here, the swan, a mythic creature associated with beauty, plummets dramatically.

“I was looking at historical works and seeing these 18th-century British still lifes of swans killed in a hunt. I felt like it could be a stand-in for women,” the artist noted. “In my work, I try to get to the heart of these universal experiences of girlhood and womanhood and I enjoy using still lifes as allegories for the female experience.” In some ways, the image is reminiscent of Zurbarán’s famous painting Agnes Dei (1635–1640)a tender, heart-wrenching image of a sacrificial lamb, bound but alive, a symbol of purity heading towards demise. “I wanted the swan to have agency,” she explained of the image. “It’s still a choice and a little bit open-ended and unclear. Self-destruction to one person doesn’t look the same to another.”

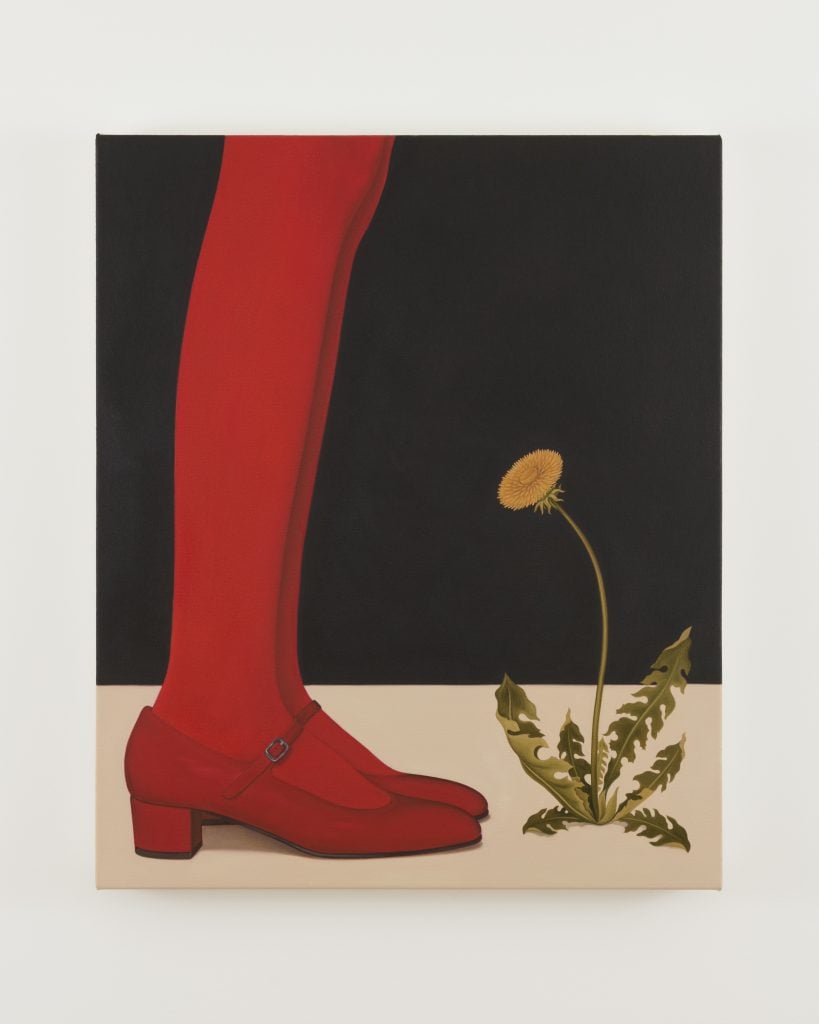

Meghann Stephenson, Why Be A Cut Flower When You Can Be A Weed? (2024). Courtesy of the artist and Half Gallery.

But not all moments of action are rooted in oblivion in Stephenson’s painted world. Beside Swan Dive hangs the painting Why Be a Cut Flower When You Can Be a Weed? Here, a woman’s legs are visible in red tights and red patent leather Mary Janes. She stands a visible ground, in front of a dandelion. The image is oriented in space, rooted, in a way her other paintings are not. Here, the unseen woman seems to parallel the dandelion before her. For this image, Stephenson was inspired by “tall poppy syndrome” a phenomenon in which people are criticized for their successes as well as by The Red Shoes, a fairytale by Hans Christian Andersen in which a young girl is repeatedly punished for loving a pair of red leather shoes.

“People tend to cut you down if you’re too smart, talented, pretty, too anything,” Stephenson said. “I like to use flowers as representations of women, but I thought if a flower is so delicate, is there something similar but maybe sturdier? Then, I thought of a weed growing up through the cracks. The painting is a portrait, even if not traditionally so. This might not be what everybody sees as durable and strong, but this is where I see it.”