Reviews

What Makes Melissa Cody’s Vibrant Art Tapestries So Powerful to Me

"Webbed Skies" at MoMA PS1 takes us on a journey from No Water Mesa to the Rainbow Road.

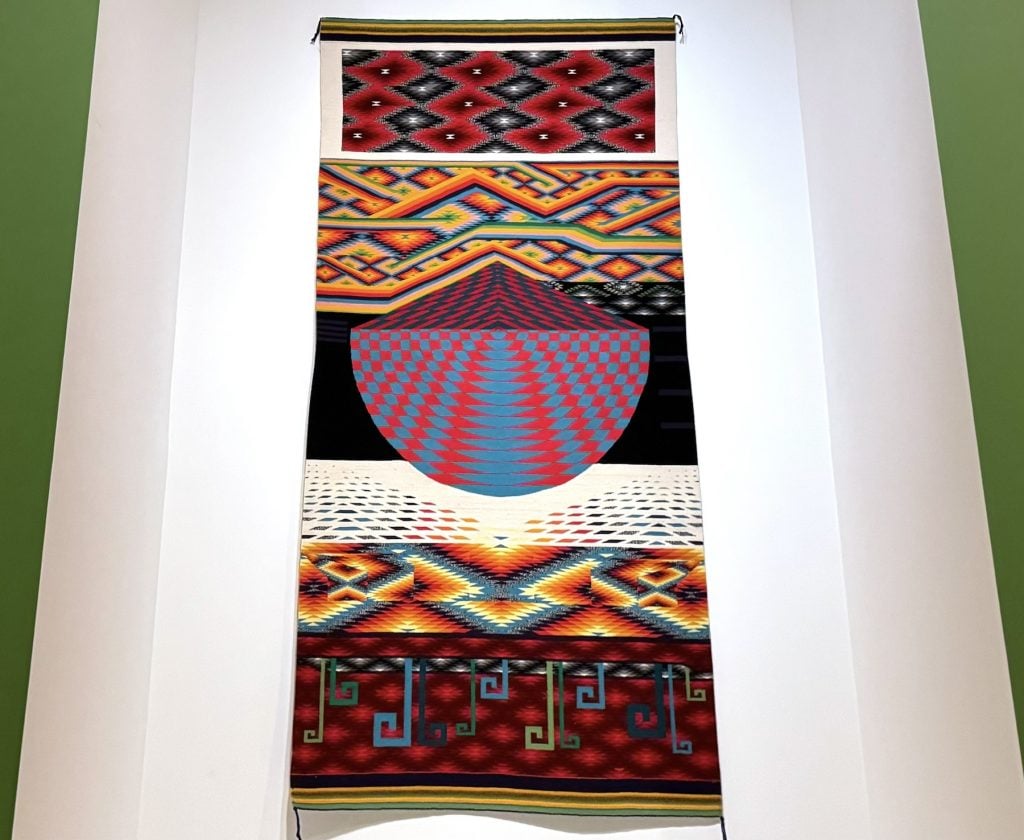

World Traveler (2014) is displayed in an alcove at the heart of Melissa Cody’s assured solo show, “Webbed Skies,” at MoMA PS1 in Queens. The abstract wool wall hanging channel-changes between multiple patterns up and down its length. It plays with symmetry and rhythm—no two sections obey the exact same rules. In places it has an almost Op Art density, sometimes implying depth that draws the eye in, sometimes suggesting a flow that sweeps you left to right or up.

A looming semicircle checkerboard at its center is a flourish, a statement of individual ambition designed to attract attention (making a curved border work is tricky in gridded fiber, let alone sixteen nested ones!). Check out the related works of Navajo/Diné weaving in the collection of the Stark Museum of Art in Orange, Texas, which owns the piece. There’s nothing else like it.

World Traveler is beautifully controlled chaos—a delightful, deliberate tour de force.

Melissa Cody, World Traveler (2014) in “Webbed Skies.” Photo by Ben Davis.

Cody, who was born in 1981, hails from a remote community in Arizona with the starkly evocative name of No Water Mesa. She comes from a line of weavers, including both her mother and grandmother. Her aunt, Marilou Schultz, was once commissioned to make a tapestry depicting a circuit board for Intel in the ‘90s (it was shown in Documenta 14 back in 2017).

Visiting “Webbed Skies” I learned some things about traditional Navajo/Diné symbols: the hourglass shape that symbolizes “spider woman,” the goddess associated with weaving; the serrated “eye dazzler” patterns that occur again and again, an adaptation of a traditional Mexican motif; and so on.

But the exhibition also shows an artist spinning up her own symbolism to capture her own experiences and feeling of the present. “Whereas I learned to weave with a more artistic-minded approach, my mother and other relatives learned by necessity—they had to clothe themselves and put food on the table,” Cody told Elephant earlier this year.

Melissa Cody, White Out (2012). Photo by Ben Davis.

A small work, White Out (2012), made during Cody’s formative studies at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, is a kind of mini manifesto in wool. It features a symmetrical, saw-toothed “eye-dazzler” in greens, oranges, and blues, interrupted by two stark cream-colored rectangles at the left. It feels like the impulsive clash of two systems, but of course it’s actually all one carefully executed design. The patches jut in to exactly the center as if to suggest not just disruption of convention, but an artist seeking a balance between disruption and convention.

“Webbed Skies” is not a large show (it began, incidentally, at the São Paulo Museum of Art as part of Venice Biennale curator Adriano Pedrosa’s year of culture dedicated to Indigenous artists from around the world). It contains just a little over 30 textile works, across three galleries, some of them imposing like World Traveler, some smaller, like White Out. Still, the show captures the sense of what is exciting to me about the current swell of international institutional interest in textile art—which has been so sustained that it can’t be called a trend, though it is not so widespread as to feel secure.

Installation view of “Melissa Cody: Webbed Skies,” on view at MoMA PS1 from April 4 through September 2, 2024. Photo: Kris Graves.

Textile art has met the moment for a variety of reasons—some of them contradictory. Textiles can connote connection to tradition and community. Their tactility and embodied relation to making appeals to a wide audience at a moment when creativity seems very dematerialized and disrupted.

But, as Brian Boucher found in a recent article, textiles can also be sold as the very template of an industrial art, with the punch-card operations of the Jacquard loom contextualized as the first computer. Cody made complex recent works in “Webbed Skies” remotely, sending digital patterns to high-tech looms in Belgium instead of using the traditional upright Navajo hand loom.

The gridded patterns of weavings can also be thought of as pixel art, avant la lettre—an association Cody embraces. In the audio guide, she talks about how the hints of spacey psychedelia in World Traveler deliberately tease memories of riding the “Rainbow Road” from Nintendo’s Mario Kart.

Artists can be simultaneously confined and empowered by the imagery of tradition—pressed to ditch it to develop an individual brand, while pressured to adopt it to fit some stereotypical idea of what “Native weaving” might look like. The turbulence from these competing demands probably intensifies as the world accelerates, as people, images, information, and artworks move around more rapidly and collide in new ways (the exuberant and ever-twisting obstacle course of the “Rainbow Road” actually is a nice organic symbol for this condition, now that I think of it).

Portrait of Melissa Cody. Melissa Cody Working in Her Studio. 2023. Courtesy Graham Nystrom. Photo: Graham Nystrom.

There’s a lot going on in “Webbed Skies.” Some experiments I like a little less and some a little more. I ended up being most drawn to World Traveler because it captures this core creative drama at the level of pattern.

The symmetries and repetitions of the traditional Navajo textile motifs contain plenty of room for expression and innovation, of course. But their ordered geometry intuitively conveys a feeling of preserving a worldview and a stable set of relations to a world—to the land, to community, to tradition.

World Traveler also expresses a mental map of relations in fiber. But it is, as the title suggests, about the sense of moving between different worlds and multiple patterns of life that pull at you. Cody captures the strangeness of this present, and the beauty that can come in navigating that strangeness, and she makes having that particular conversation in this particular medium look so natural.

“Melissa Cody: Webbed Skies” is on view at MoMA PS1 in Queens, through September 9.