Style

A New Book Explores How Andy Warhol’s Notions of Pop Foresaw the Union of Art and Fashion—Read an Excerpt Here

"Merchants of Style: Art and Fashion After Warhol" is out now.

"Merchants of Style: Art and Fashion After Warhol" is out now.

Natasha Degen

The following essay has been adapted from the new book Merchants of Style: Art and Fashion After Warhol by Natasha Degen (Reaktion Books, 2023).

Natasha Degen is Professor and Chair of Art Market Studies at the Fashion Institute of Technology. She earned an AB from Princeton University and an MPhil and PhD from the University of Cambridge, where she studied as a Gates Scholar. She edited The Market (MIT Press, 2013), an interdisciplinary anthology tracing the art market’s interaction with contemporary practice, and has written for publications including the New Yorker, the Financial Times, the New York Times, Artforum, and Frieze.

As luxury fashion opened its doors to a more expansive audience, Pop art, with its vernacular imagery, was becoming a mass phenomenon. “Pop go the clothes!” the Herald Tribune announced. “What started with Pop Art, like Andy Warhol’s Tomato Soup Cans, has suddenly become Pop living!” Saint Laurent had seen Andy Warhol’s exhibition at the Sonnabend Gallery in Paris in May 1965 and met the artist when Warhol returned to France the following year. “Andy was one of the few artists to be doing something new and different with painting,” Pierre Bergé recalled. “All his work—his Maos, his flowers, his use of photographic images—made a big impression on us.” Warhol, like other exponents of Pop, had become notorious for challenging the definition of art by refusing its capacity for transcendence. In contrast to the art of the previous generation, Abstract Expressionism, which was defined by striking gesture, emotional intensity, and lofty ambition, Pop approached its banal subject matter with detachment and played with the tropes of consumer culture. To its critics, Pop not only demeaned itself by associating so closely with commercial design but dragged art down with it in collapsing high and low.

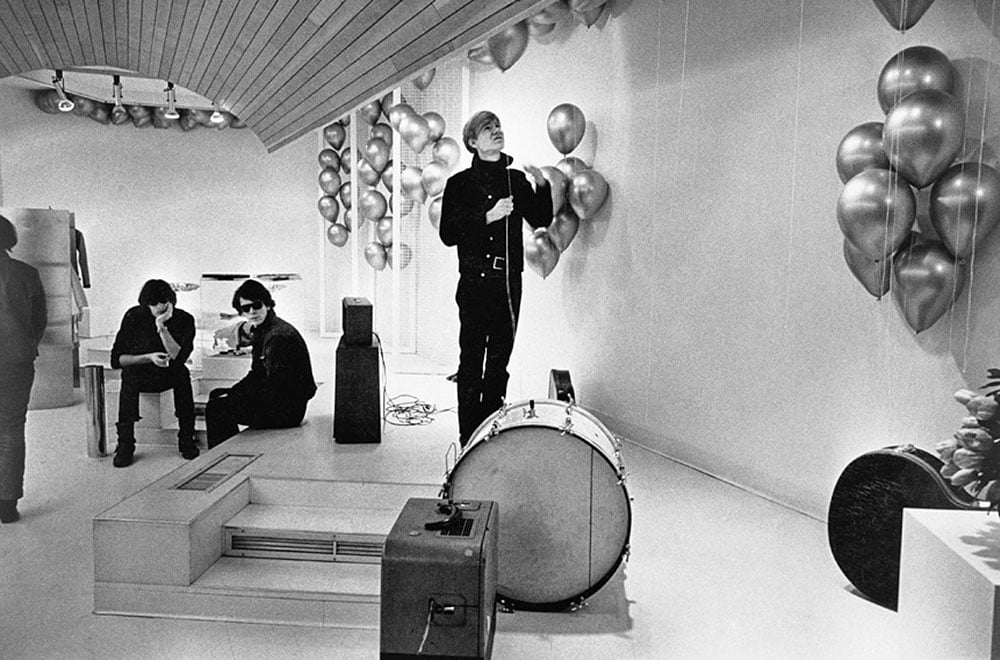

By the mid-1960s, as Saint Laurent looked to art, Warhol, a former fashion illustrator, turned his attention to fashion. He was fascinated by what fashion had become and the celebrity culture that had sprung up around it. He promoted a cast of personalities he dubbed “superstars,” who, according to the critic Peter Wollen, were “plainly based on [the] new generation of young fashion models from London” like Twiggy and Jean Shrimpton. After returning from Paris in 1965, fresh off his Sonnabend show, Warhol hosted the opening party for the boutique Paraphernalia at the invitation of designer Betsey Johnson. Conflating art and fashion, the store “resembled an art gallery more than a conventional retail space.” Its aesthetic was minimalist and the merchandise mostly hidden from view (sales were confined to the second floor). Its architect conceived the store as “a continuous Happening.” At a party the following year, Warhol’s films were projected on the store walls. Edie Sedgwick, the most prominent of Warhol’s “superstars,” became Johnson’s fitting model.

Andy Warhol setting up at Paraphernalia boutique, with Sterling Morrison and Lou Reed, New York, 1966. Photo: Nat Finkelstein. Courtesy of Reaktion Books.

If couturiers like Worth and Poiret, who portrayed themselves as artists, represented the first phase in the story of art and fashion’s promotional synergy, and the Surrealists, who abandoned any reluctance to engage in commerce and collaborated directly with the fashion industry, represented the second, the Pop generation of the 1960s, whose work presaged an organic convergence of art, fashion, and mass culture, marked a distinct and crucial third phase. In many ways the art-fashion nexus of the 1960s elaborated and deepened trends that reached back to the Surrealists. But whereas Paris, the context of the Surrealists’ border-transgressing collaboration, had long celebrated fashion as part of a high-culture milieu, post-war New York did not hold fashion in the same esteem. The new, third phase that arose in New York reflected the rise of mass media and the growing power of brands. These critical developments taught art and fashion to regard the other as a means to mass culture salience.

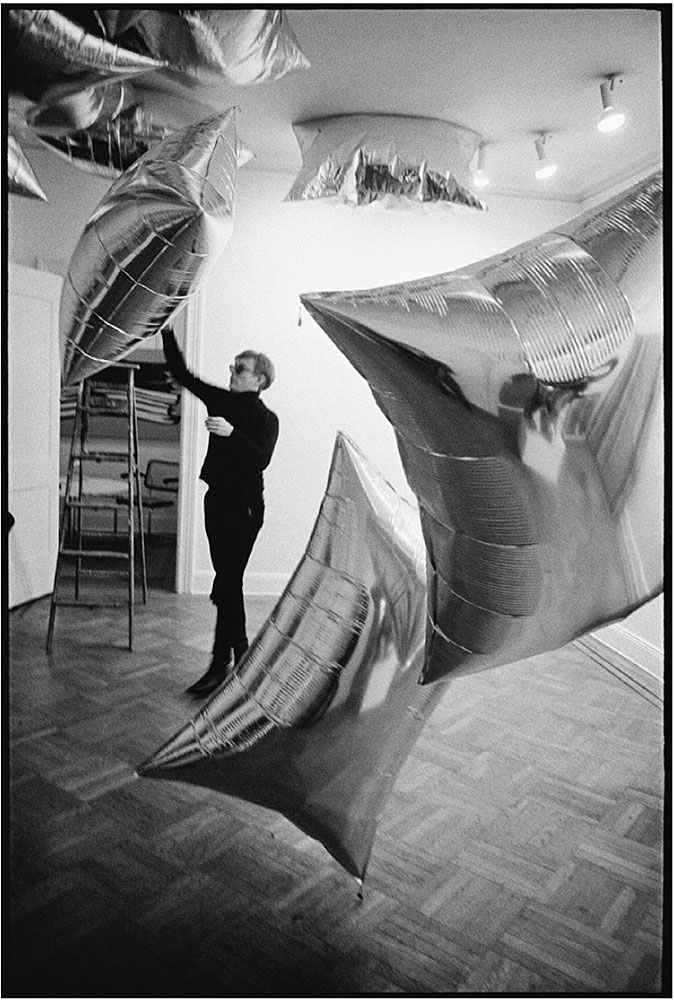

Andy Warhol installing

Silver Clouds at the Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, 1966. Photo: Nat Finkelstein. Courtesy of Reaktion Books.

Aesthetic borrowing and overlap proved inevitable, with new materials ubiquitous in both fields. Through his friend the engineer Billy Klüver, Warhol discovered mylar, a reflective polyester film then being used by NASA in balloon satellites. The material inspired his Silver Clouds installation, a work composed of silver balloons, which debuted at the Leo Castelli Gallery in 1966. Paraphernalia’s garments, often made of plastics, adopted a similarly shiny and disposable aesthetic—part space age, part amphetaminic delirium. “We were into plastic flash synthetics that looked like synthetics,” Johnson recalled. “It was: ‘Hey, your dress looks like my shower curtain!’ The newer it was, the weirder—the better.” The vogue embraced metals and metallics, as illustrated by Mademoiselle‘s 1965 fashion feature titled “Silverfoil.” (Warhol’s studio during these years, covered in tinfoil and silver paint, came to be called “the Silver Factory”.) Warhol himself dabbled in throwaway fashions. He created dresses out of paper (another new fashion material), screenprinting his designs directly onto a blank paper dress worn by singer Nico in a live performance at Abraham & Straus, a Brooklyn department store. “It’s a Happening!” an A&S advertisement exclaimed. “See Andy Warhol Paint a Paper Dress on Nico.” Art and fashion alike endorsed impermanence and artificiality: the qualities of mass-produced consumer goods.

While fashion was rejecting couture’s rarefaction, art was renouncing the self-seriousness of painting. For Warhol, painting had become “old-fashioned”; his Silver Clouds represented a break with the venerable medium. As Marylin Bender put it at the time, “If Pop art can be construed as a reaction to abstract expressionism, so pop fashion is a rebellion against precious clothes.” A new, more demotic culture was emerging. “No longer was the latest fashion being dictated by Parisian couturiers and the wealthy elite,” Richard Martin explained; “now the media and the youth culture could make up their own minds.” Art disowned its special status, becoming more porous to the wider world, while commercial culture also expanded its reach. As a result, the two now appeared to exist on the same continuum, governed by the same mass-media regime. A model posed in front of Warhol’s Silver Clouds in Vogue; members of the Factory set wore “underground” clothes in Life magazine, with Warhol’s underground films projected onto them. The art world became captivated by fashion. “It’s called Opening Night At An Exhibit of New Art, but the objective is to get as much attention as possible by wearing the wildest thing,” Women’s Wear Daily noted in a 1967 article covering the reception for an Yves Klein exhibition at the Jewish Museum. (The article proceeded to describe some of the night’s most eye-catching outfits.) “Pop art may have come first and become more famous, but pop fashion followed soon after,” Eugenia Sheppard wrote in 1965. “They meet these days at the art galleries.” For the first time since the Surrealists, a revolving door had opened between segments of the art and fashion worlds. But this time mass media amplified the effect. The reach of media unlocked a latent promotional potential that art and fashion, as industries of symbol and style, had yet to fully realize.

The symbiotic benefit art and fashion discovered in their mutual association brought the fields closer still. Each assumed attributes of the other. By aligning itself with art, fashion could promote an image at once more sophisticated, novel, and exclusive than it had managed on its own. The art world, by contrast, embraced an alluring idea of itself that drew on trendiness, celebrity, and glamor. In a manner reminiscent of the fashion-show circuit, the art world increasingly organized itself, in the decades that followed, around a calendar of international, media-friendly events: the exhibition opening, the auction, the biennial, the art fair. As art and fashion converged, they claimed a shared place in the cultural imagination: a composite realm of aesthetics and “lifestyle,” at once amorphous, beguiling and highly salable.

Some twenty years after Pop, Saint Laurent continued to mine art for inspiration. Warhol, for his part, devoted himself more fully to fashion. In 1988—at a moment when the market for Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painting was reaching stratospheric heights—Saint Laurent created beaded jackets based on Van Gogh’s Irises and Sunflowers, at the time the two most expensive paintings ever sold. The jackets seemed to reference the paintings’ valuations directly in the opulence of their materials and preciousness of their construction (to say nothing of their exorbitant prices: $85,000 each). Until his death in 1987, Warhol continued to investigate the nature and seduction of celebrity and style. He was an image-maker in both senses of the term. Warhol pulled images from the mass-cultural ether and isolated them, rendering them indelible and iconic. But he constructed immaterial “images” as well, fashioning personae and making myths out of the “superstars,” the Velvet Underground and indeed himself. Warhol cultivated a signature look, ensuring instant recognition. He pushed his exploration of image-making further in his Screen Tests, which harked back to the Hollywood studio system, and in Interview magazine, which he founded in 1969 to more deeply penetrate the celebrity demimonde.

Warhol was fascinated by the centrality of fashion and style in creating the mystique on which celebrity rests. Glenn O’Brien, a former editor of Interview, recalled that the magazine gravitated towards fashion “naturally and quickly.” It covered up-and-coming designers such as Halston and Giorgio di Sant’Angelo and established designers like Charles James and Rudi Gernreich. Diana Vreeland, the former editor of Vogue, graced the magazine’s December 1980 cover. At the same time, Warhol’s obsession with fashion led him to host a ten-episode television series called Fashion (1979-80), which he described as a “fashion magazine on TV.” Later, Warhol would claim that the Leonardos and Michelangelos of his day were in fashion, like “Armani…and the other Italian designers.”

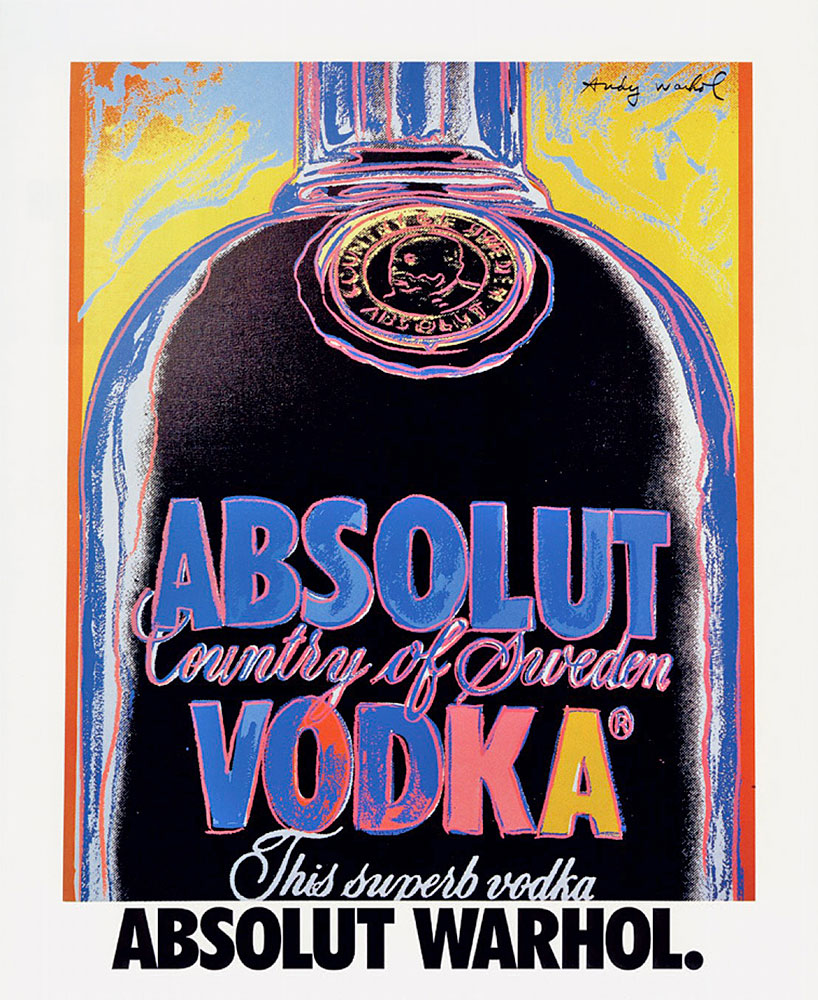

In addition to being arguably the most influential artist of the post-war period, Warhol’s aesthetics continue to inspire fashion. But Warhol’s approach to “Business Art” has proved his most consequential legacy for art and fashion alike. Warhol’s pioneering ad campaign for Absolut Vodka exemplified this approach. In 1985, he had suggested the idea to Michel Roux, the CEO of Absolut’s U.S. distributor. Warhol received $65,000 for his painting of Absolut’s iconic bottle and sold the reproduction rights for five years. Despite doubts from the company’s advertising agency, Roux saw the campaign as a way to create a “fashionable” brand identity, linking Absolut to the art world and attracting “society people”: artists, Hollywood, the rich, the famous. At first, the company was cautious, running the ads only in art magazines, but the response was so positive that the ads were soon ubiquitous.

Andy Warhol, Absolut Vodka (1985), screenprint on paper. Courtesy of Reaktion Books.

Warhol was interested in consumer culture writ large, but fashion held a particular fascination for him. It was fashion, after all, that established the potential for marketing products by emphasizing not their utility but their symbolic meanings. Purveyors of fashion laid the ground for an idea of commodities not primarily as functional items but as tools of self-branding, of personal image-making. Consumers could signal any number of postures (stylishness, practicality, frivolity) as well as wealth, social status, and group affiliation.

If we define fashion narrowly as dress, or perhaps as shorthand for the garment industry, its influence on the nascent consumerism of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is readily evident. But if we expand our understanding of the term to encompass the concept of continuous obsolescence—of cyclic and supplanting styles—its influence on consumerism becomes still more acute. In this sense, “fashion” is the ur-subject of Warhol’s work. By reproducing advertisements and press images in his art, Warhol emphasized the inherent transience of visual culture alongside its capacity for iconicity. He was concerned with the independence of promotional imagery’s allure from that which it promotes. In foregrounding the advertisement as the thing, the emotional experience, in itself, he trained our attention on the process by which the icons fashioned by advertisers become our cultural inheritance of symbols and images, and thus stand ready for an afterlife in the timelessness of art. Warhol himself was often the ferryman across this divide.

The effectiveness of artist-branded products, like Warhol’s, helps to explain the cross-pollination—the hybridization—prevalent in today’s creative economy. Whereas modernity separated different spheres like art and fashion, so that “each one had its own compartmentalized, rational world,” we now have a “preference for conjunction over disjunction,” as Gilles Lipovetsky has said. Art and fashion—increasingly subsumed by market forces, transformed by consolidated power, and governed by the growth imperative—find incentives to look beyond their borders, to other industries but above all to each other. With this amalgamation, distinctions between fine art and applied art fade into irrelevance.

Excerpted from Merchants of Style: Art and Fashion After Warhol by Natasha Degen (Reaktion Books, 2023).