Meriem Bennani’s video installation, Party on the Caps, now on view at CLEARING gallery in Bushwick, evokes a genre that I don’t know quite how to describe. “Dystopian art mockumentary” gets close, but not all the way there. It’s confounding and unsettling and funny, and also pretty great.

Bennani (b. 1988) hails originally from Rabat, Morocco, but studied at Cooper Union in New York. She’s known, among other things, for her zany Instagram art; for her recent solo show at MoMA PS1 (featuring a multi-channel Moroccan travelogue told from the point of view of an animated fly); and for gawky sculptural video installations featuring interviews with Moroccan teenagers that were featured as part of the Whitney Biennial. (She was one of the artists who threatened to pull her work as part of the successful campaign to remove teargas magnate Warren Kanders from the museum board.)

Party on the Caps, too, features oddball sculptural elements, including bleachers clad in fake albino crocodile skin, irregularly sized glowing cylindrical seats, and a wonky multi-screen set-up that fragments and sometimes warps the projected images. This scenography amplifies the atmosphere of the onscreen action, which depicts a world of familiar but perplexingly mutated human relations.

Installation view of Meriem Bennani, Party on the Caps (2019). Image: Ben Davis.

As for what the onscreen action of this half-hour film actually consists of, that is hard to express exactly—despite the fact that the film effectively plays in two parts, the first of which is a prologue that actually features a voiceover that just lays out the rules of the world in the movie. It’s just that those rules and that world seem to have their own internal logic that takes some decoding.

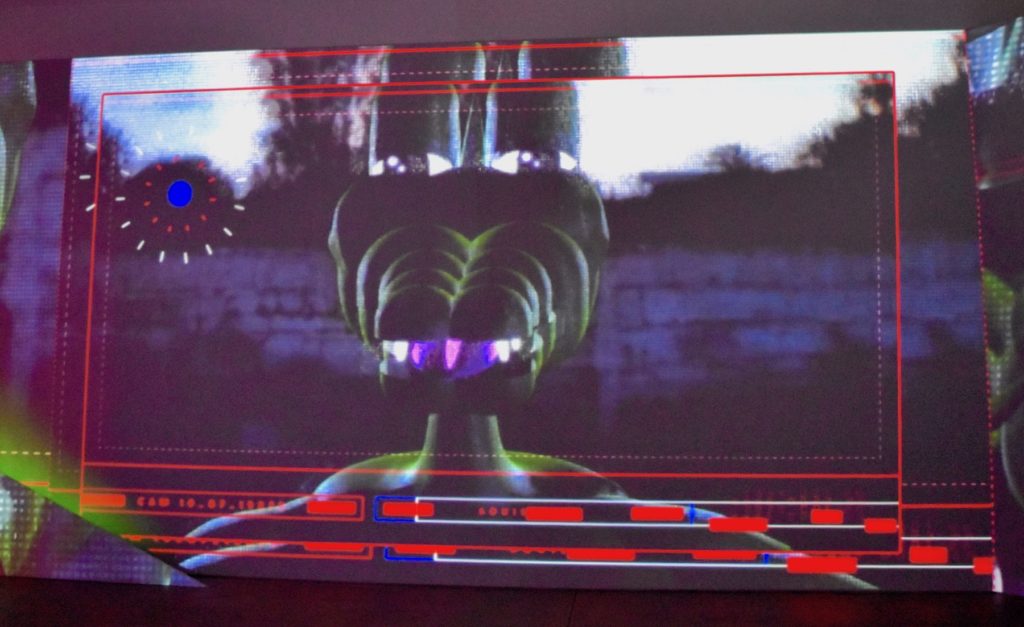

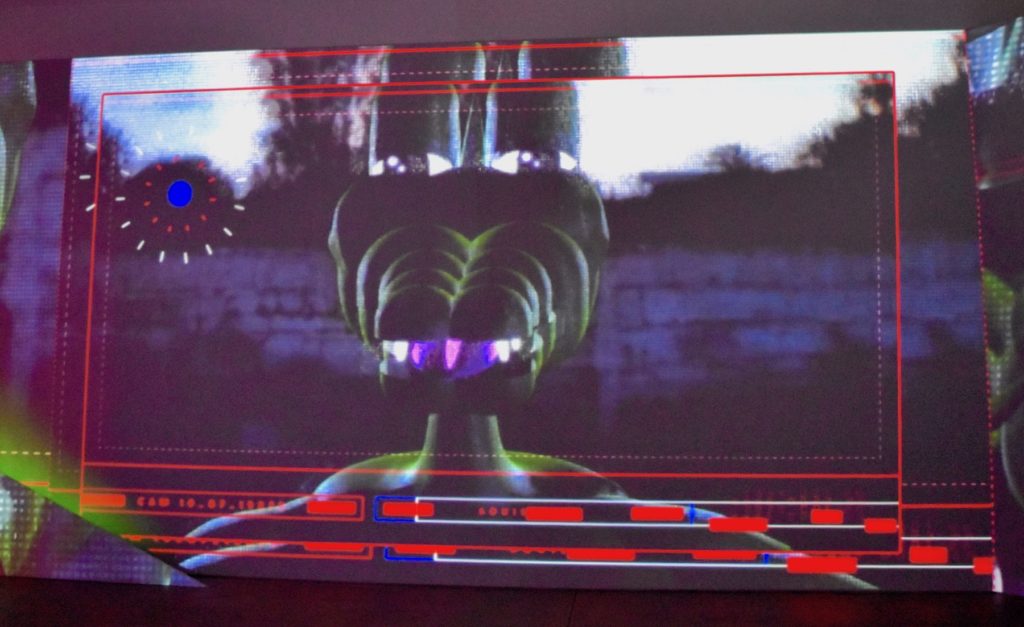

From the prologue to Meriem Bennani’s Party on the Caps (2019). Image: Ben Davis.

Party on the Caps is set mainly in a Moroccan neighborhood of an island in the Atlantic called the Caps that has been set up as a prison for unwanted immigrants in a future where teleportation has become the travel norm. People deposited in the island’s shantytown are immigrants who have been intercepted mid-teleport by American “troopers,” who appear in the film as circling drones—bright, ominous, watchful spots hovering in the distant sky. Some residents of the Caps suffer strange disorders (“plastic face syndrome”) as a consequence of being molecularly intercepted and reassembled.

“We don’t take anything for granted here—not even bodies!” the narrator says in the intro, over the comic image of two shoes walking by themselves.

Installation view of Meriem Bennani, Party on the Caps (2019). Image: Ben Davis.

But life goes on beneath the prison island’s dome. Residents have access to holographic technology that allows them to send messages, transfer money, and amuse themselves in various ways. Oh, and the island is full of crocodiles, and the crocodile is apparently the symbol of the Caps, recurring in different forms everywhere—including as a clunky, animated humanoid crocodile who intermittently serves as our narrator.

Installation view of Meriem Bennani, Party on the Caps (2019). Image: Ben Davis.

To call what you see in Party on the Caps a “story” would be too strong. The core of events is the titular party, featuring dancing, drumming, and an MC rapping gleefully about life on the island. At different points, there is pseudo-documentary footage with people musing about life in Caps society. There is an extended interlude with a large sinister animated cartoon face that fills the screen and grins out of the darkness, representing, it seems, a kind of AI smuggler, promising Caps residents that they can be beamed into a new life in Florida for the right price (“I have gorgeous bodies in America waiting for a second run”). There are also snippets that suggest alternate-universe commercials and TV shows full of crocodile symbolism.

Installation view of Meriem Bennani, Party on the Caps (2019). Image: Ben Davis.

I can imagine a criticism about this film: That for a work that is quite evidently about something very horrible and topical—America’s techno-powered global police state and the criminalization of refugees—the moody but playful tone is off. Despite dystopian intimations, nothing that happens in Bennani’s video is even close to being as horrifying as what you’re reading about in daily headlines. There’s a party. There are petty conflicts and hierarchies but everyone seems to be at least getting by, eating well (or at least eating “Croco”-branded cereal), taking care of their families, and so on, in the shadow of those faceless trooper drones.

Installation view of Meriem Bennani, Party on the Caps (2019). Image: Ben Davis.

“Dream-like” is an overused term, but Party on the Caps really is dream-like in a strong sense. Certainly, in the way that it circles through symbols and seems to obey its own sui generis narrative logic. But also in that it seems like a very personal vision: Bennani has cast her own mother in a key role, an aspect that is symbolically important enough that the gallery is handing out transcripts of the conversation Bennani had with her bemused mother as she was trying to teach her the film’s dialogue. So overall the video really reads as a rebus of present-day personal anxieties, strained through sci-fi fabulation.

Installation view of Meriem Bennani, Party on the Caps (2019). Image: Ben Davis.

It’s dream-like too in a way that is very difficult to capture in art: the characters or events seem to be suffused by an emotional resonance utterly different from what those characters look like outwardly. The final, gloriously odd image of a dead-eyed cartoon crocodile standing watch in the night, Terminator-like, leaves behind an aftertaste of pronounced Surrealist spookiness.

In fact, the aura of puzzling-ness and incongruity here seems to be a reaction to the alarming and virulent demands of the present moment. In an interview two years ago with Art21, in the wake of Trump’s initial travel ban, Bennani spoke of the contradictory feeling of being deeply personally affected by the news, coming from a majority Muslim country herself, while at the same time bridling at being stereotyped and pigeonholed as a “Moroccan or Muslim woman artist.”

“What this political climate does,” Bennani said, “is that it asks you to think about your identity constantly. And I feel like my reaction to that has been to make work that itself doesn’t stick to one genre or identity. It has to do with me not wanting to define myself into one thing.”

Installation view of Meriem Bennani, Party on the Caps (2019). Image: Ben Davis.

Culture is overrun right now with dystopian imagery; it is the default mis-en-scene of any future imagining. This is very obviously accelerating because the present is full of horrors that seem only to be looming larger.

For me, Bennani’s Party on the Caps, with its combination of quirky personal symbolism, knowing sci-fi tropes, and the everyday-ness of its depicted events—getting by, going through the cultural rituals and social devices that make life bearable—specifically cuts against the suggestion that it’s a Black Mirror-ish prophecy about Things To Come.

It seems to me that Party on the Caps serves a different function. As much as it extrapolates present-day anxieties into a sinister cartoon of a terrifyingly broken world, it also doubles as a love letter to the sustaining resilience of family and culture amid the chaos. Bennani’s spooky but joking tone may represent something like nervous laughter about whether the fantasy actually holds together, about whether the threat of the former doesn’t strain the latter in unthinkable ways. At any rate, the film is balanced between giving a serious sense of a world out of control and domesticating dystopian thoughts with whimsy, so that it is as much about coping in the present as it is about peering nervously into the future.

“Meriem Bennani: Party on the Caps” is on view at CLEARNING, through October 27, 2019.