Beantown has become New New Amsterdam, with the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston nearly doubling its Dutch and Flemish holdings, adding 114 donations, promised gifts, and loans from two collecting couples, Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo and Susan and Matthew Weatherbie.

The works, jointly promised to the MFA in 2017, are now on view, some of them for the first time

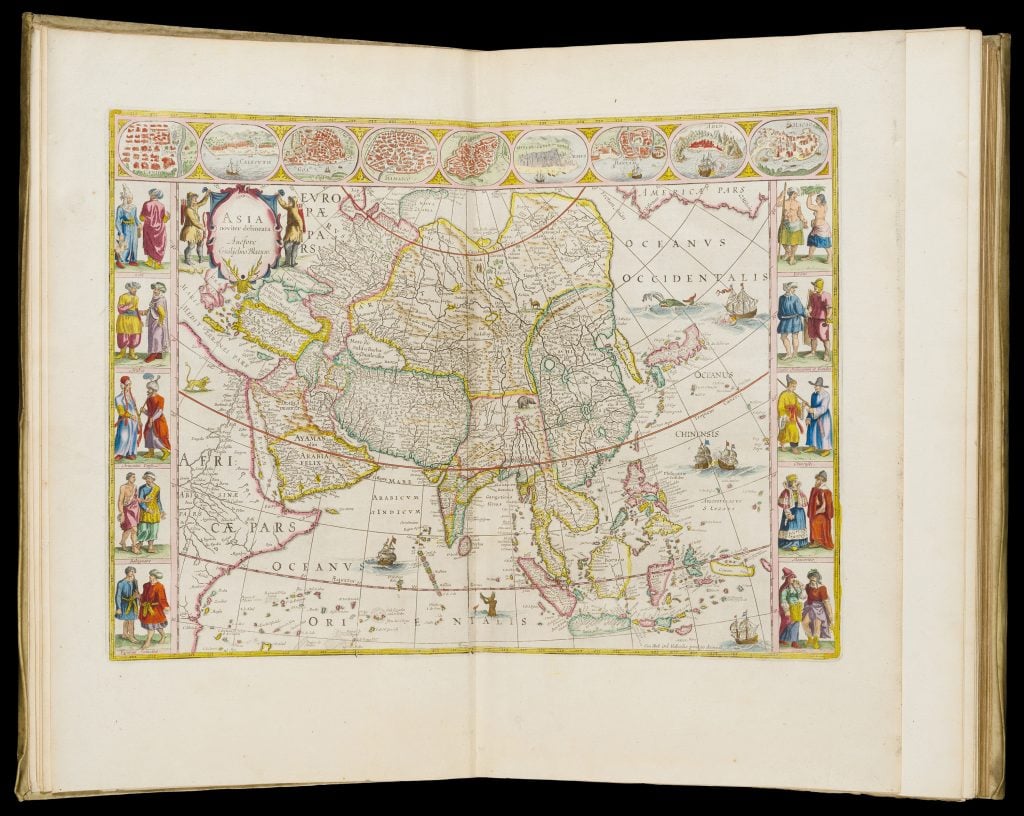

Reinstalled Dutch and Flemish galleries and a new Center for Netherlandish Art, boasting 43,000 volumes, including Dutch and Flemish books gifted by the van Otterloos, plus working space for visiting scholars, propel the 151-year-old institution into elite company.

The MFA Boston’s new Center for Netherlandish Art. Photo: Menachem Wecker.

As with Impressionism, the MFA will be known for its Dutch and Flemish art, with just the Metropolitan Museum of Art and National Gallery of Art boasting better holdings stateside, said Frederick Ilchman, the MFA’s European art chair.

“We may never have the late Rembrandts, and there is no chance of getting a Vermeer, but in everything else, we are now as strong or stronger,” he said.

During a several-hour tour, Ilchman told Artnet News the MFA prioritized spotlighting women artists and emphasizing how colonialism and slave labor underpinned many works. Visitors and scholars may split on whether the MFA balanced appropriately celebrating art and indicting those that conceived it, but all will agree likely that it has installed masterpieces thoughtfully.

Rachel Ruysch, Still Life with Flowers (1707).

The New Old Masters

Standing before Rachel Ruysch’s Still Life with Flowers (1709), Ilchman noted the artist pioneered es-curves that animate flower compositions. “Ten years ago you would say, ‘The best known woman flower painter was Rachel Ruysch,’” he said. “We’re just calling her, ‘One of the best flower painters,’ because that’s what she is.”

Several works required reattribution. A quintipartite series on “The Five Senses” (1650) by Flemish artist Michaelina Wautier is part of a repertoire of just 30 or 40 known works, and the series was initially given to another artist.

“Any museum would be glad to have one,” Ilchman said. “It was just old-fashioned sexism that wrote her out.” Despite Smell depicting a rotten egg, the series hangs in a rotunda where the MFA hosts receptions with food. “We’re trying to make a statement that a woman artist can be right at the center here,” Ilchman said.

Another gallery features a rare Judith Leyster self-portrait (c. 1650)—which fetched $593,883 at Christie’s on December 8, 2016 in an Old Masters sale—from a private collection, and Maria Schalcken’s Self-Portrait of the Artist in Her Studio (c. 1680), which was given to her brother, Godfried, until her signature was discovered.

Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn, Artist in His Studio (about 1628).

The latter faces Rembrandt’s Artist in His Studio (c. 1628), famously hiding the canvas-within-a-canvas from the viewer. Ilchman thinks it portrays “the intimidation of starting a large project” and Rembrandt pondering the onset of his career. Nearby, Jan Davidsz. de Heem’s c. 1630 Interior of a Painter’s Studio appears to respond to Rembrandt, Ilchman said.

Alongside a doll house—variously composed in the 17th and 18th centuries—Rembrandt’s 1634 Portrait of a Woman Wearing a Gold Chain and Portrait of a Man Wearing a Black Hat reverses typical depictions of couples. Rembrandt painted the woman more masterfully and invitingly than the man, Ilchman noted. These two then serve as microcosms for the new galleries, in which traditional gender roles often reverse.

A wall label at the MFA Boston detailing the devastating global costs of sugar production. Photo: Menachem Wecker.

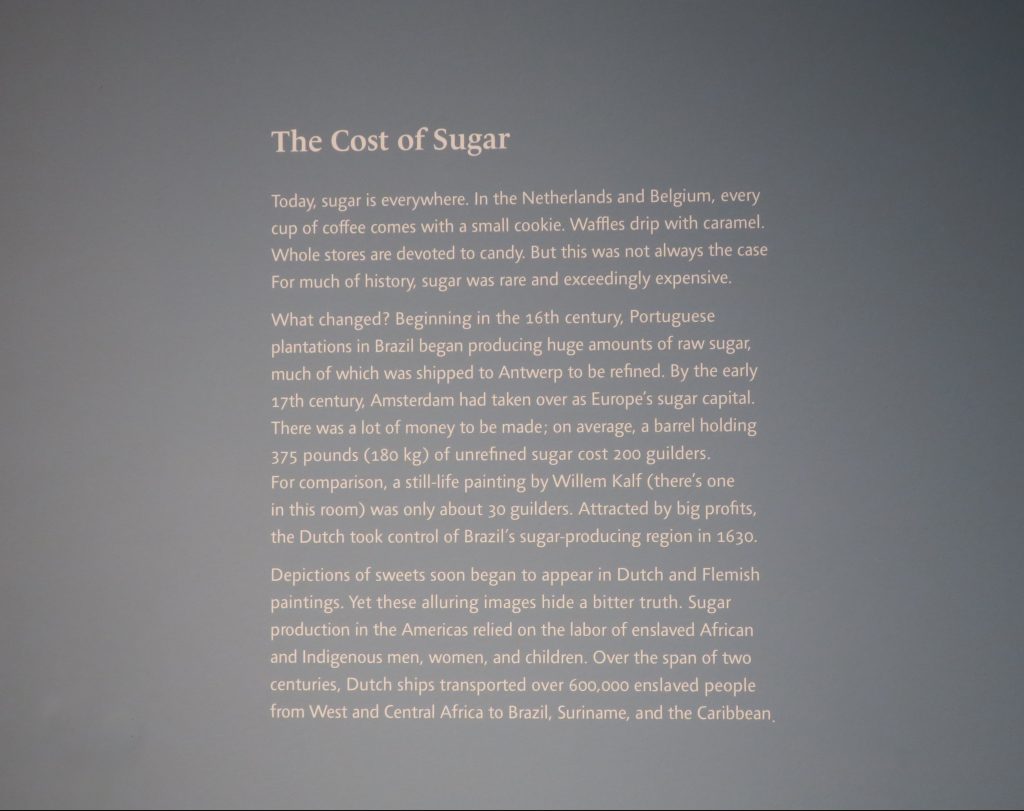

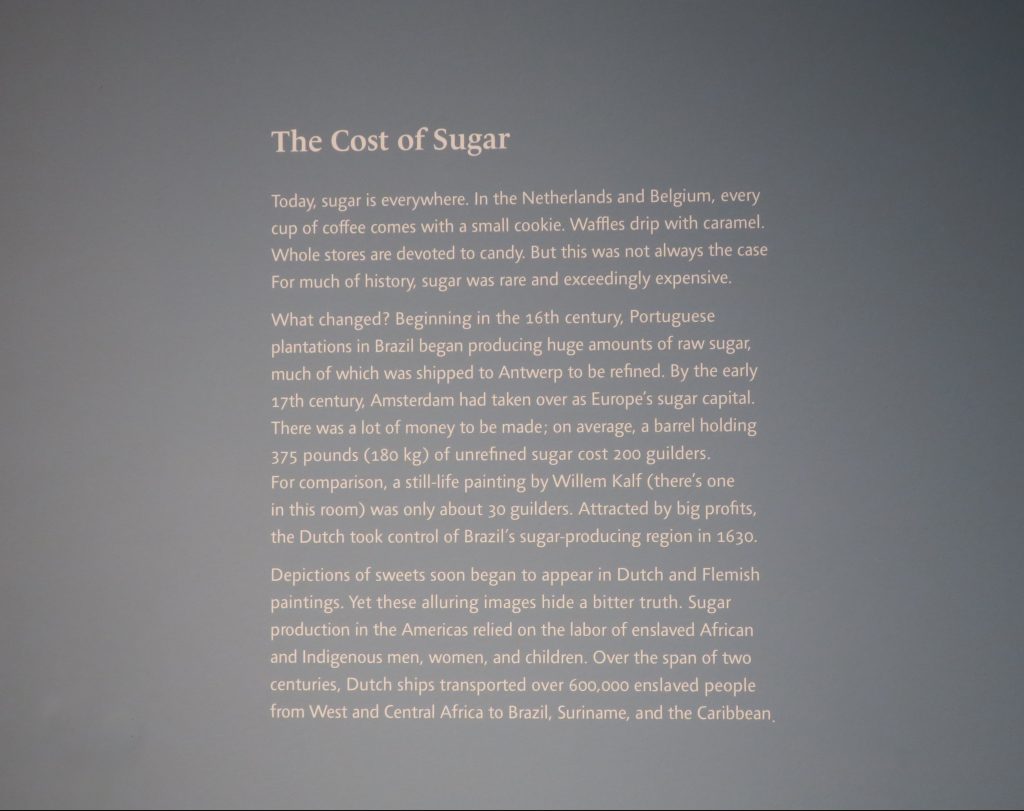

Whose Golden Age?

All that glitters is not gold, however, in galleries deliberately eschewing discussing a Dutch “Golden Age.” The Dutch 17th-century has become, of late, a proxy site into which curators infuse contemporary concerns about race, gender, and economics. The MFA’s 2015 Dutch show “Class Distinctions” addressed Occupy Wall Street, and three years later, the National Gallery was slammed for what the Washington Post’s Philip Kennicott considered downplaying slavery and colonialism in its marine show “Water, Wind, and Waves.”

In the National Gallery’s current show of the Lee and Juliet Folger Fund collection of Dutch and Flemish art, “Clouds, Ice, and Bounty,” the introductory text notes the Dutch owned colonies and participated in the slave trade, and the age “was not golden for all.” A Pieter Claesz still-life label adds that they used slave labor on sugar plantations.

Two wall texts in an MFA gallery on commerce address slavery as well. The Dutch used “coerced labor, including slavery,” adds the label to a model of the Dutch East India Company ship Valkenisse. “We’ve taken on slavery and colonialism in a big way,” Ilchman said.

Arthur Wheelock, former longtime National Gallery northern Baroque curator and University of Maryland art historian, is uncomfortable broadly with what he calls an over-correction of the “Golden Age” corrective. (Wheelock has not yet seen the MFA galleries and commented on the field, not the Boston museum’s installation.)

Holland was not a perfect society, but it has long been considered a nation that tried its best to support the poor and disadvantaged. It welcomed Jews, and allowed Catholics to worship privately, provided they did not make a fuss, Wheelock said. (Thus Holland’s “hidden” churches.) Most Dutch ships carried goods, and not all transported slaves, Wheelock said. “To pick out the Dutch and to taint the whole society because of that is complicated.”

Wheelock believes viewers can take away “humanizing messages” of dignity, love, and faith from seeing Dutch and Flemish art. “They teach one about the complexities of life,” he said. “I think it’s important to be able to speak out and say, ‘These are important. They remain important. We can all take messages from them to guide us.’”

Whether corrective or over-correction, museums may mislead visitors if they focus exclusively on Dutch 17th-century business practices, and not, say, on fabulously wealthy French kings or Russian czars, who may have also been involved in systems of human rights violations.

Out of fairness to 17th-century Dutch businessmen, shouldn’t curators also scrutinize publicly the business ventures of their present-day donors—the very ones whose philanthropy and aesthetic taste they celebrate in their labels? Cultural tax audits, after all, ought to probe evenly.