Museums & Institutions

MFA Boston Returns a 2,500-Year-Old Necklace to Turkey

When the museum bought the necklace in 1982, it did not receive any provenance records.

When the museum bought the necklace in 1982, it did not receive any provenance records.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

A gold necklace decorated with dark orange carnelian stone has been returned by the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) Boston to Turkey, where it was very likely looted from a tomb in 1976. The ancient treasure, dating from 550–450 B.C.E., had been acquired by the museum from a London dealer in 1982, a time when the art and antiques trade was much less scrupulous about ensuring an item’s origins were not marred by crime.

The MFA Boston’s open admission of its hazy acquisition of the necklace and the likelihood of its looting offers a welcome level of transparency to the deaccessioning process as many museums in the U.S. and Europe reckon with increased pressure to repatriate stolen objects.

The possibility that the necklace may have been looted was first brought to the museum’s attention by a scholarly essay from 2015. It noted that a strong resemblance to some beads and other fragments that are on display at the Turkish archaeological museum Manisa. These pieces had been excavated in 1976 at the Bintepeler Necropolis Area, following reports that the site had been targeted by looters. It seems likely, given the similarity between the artifacts, that the necklace had already been stolen from the same site.

After the MFA Boston was made aware of this connection, it began researching the object and the looting of Bintepeler. Late last year, it made contact with the Turkish ministry of culture and tourism, which also conducted its own scientific and archival research to back up the claim. The museum and the ministry reached an agreement on the legal transfer of the object.

When the museum bought the necklace in 1982, it did not receive any provenance records as is standard practice today. It was notified only that the item originated from “Asia Minor,” a term referring to ancient Antolia or modern day Turkey.

One particularly compelling piece of evidence that the necklace may have been stolen was its small size of just eight inches in length. This suggests the fragile item became fragmented at some point when it was smuggled out of Turkey.

“Most of the time, you don’t have the full item, actually, and we know that that’s true in this case,” the MFA Boston’s senior curator for Greek and Roman antiquities, Phoebe Segal, told the Boston Globe. This should have raised suspicions. “I think if we were approaching this now, we would say, ‘Why is this necklace so small?’”

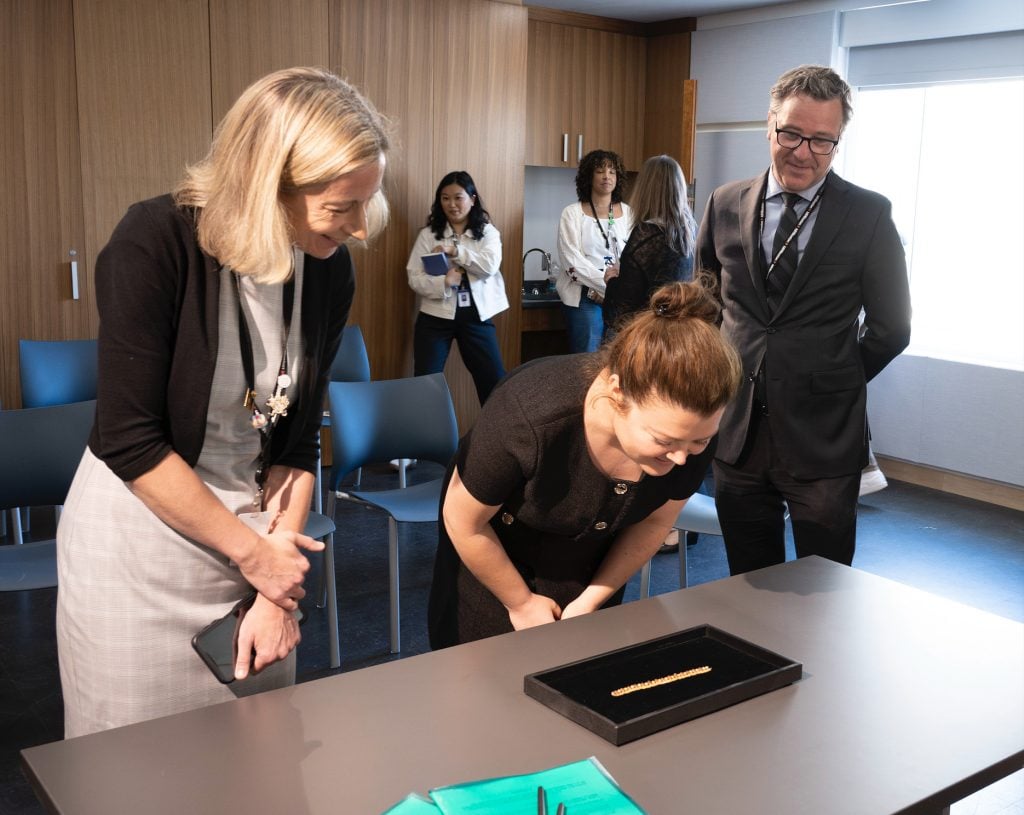

Victoria Reed, senior curator for provenance, Hilal Demirel, attaché for cultural affairs and promotion, and Pierre Terjanian, chief of curatorial affairs and conservation, examine the necklace being transferred back to Turkey. Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

“The Ministry of Culture and Tourism, together with its institutional and academic partners, is making great efforts to protect and restore Türkiye’s cultural heritage,” said Hilal Demirel, attaché for cultural affairs and promotion at Turkey’s ministry of culture and tourism. The return of an object that was illegally removed from Türkiye is a symbolic moment that sends a strong message to the world, emphasizing the importance of international cooperation in the protection of cultural heritage. It was a most gratifying experience to work on the effective resolution of this matter with the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.”

Over the past decade, a growing number of major museums in the U.S. and Europe have began collaborating with scholars and foreign governments to repatriate objects from their collection that can be shown to have been looted.

In April, the MFA Boston, which now employs a full time curator for provenance, returned a ceramic child’s coffin to the Gustavianum, Uppsala University Museum in Sweden. It had disappeared from the museum at some time before 1970 and was sold to the U.S. museum in 1985 with a series of falsified documents.

The authorities have also played a key role in cracking down on historical crimes of looting and smuggling art and artifacts, ensuring their repatriation even when the museum in question is not willing to return them.

Last year, a trove of Turkish art was seized by the Manhattan district attorney’s office during a series of raids of U.S. museums as part of “ongoing criminal investigation into a smuggling network involving antiquities looted from Turkey and trafficked through Manhattan.” Among the items repatriated as a result of these efforts was a Roman bronze leg from 180–200 C.E, deaccessioned on October 12, 2023.

One notable treasure that has now been repatriated was a 1,800 year-old bronze statue of the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius worth $20 million. Since 1986, it had been on view at Cleveland Art Museum, which said there was no evidence that the sculpture had been stolen. Other reports alleged that the museum was uncooperative when Turkey first made restitution claims on several items in its collection over a decade ago.

Since then, the call for repatriation has become much harder to ignore.