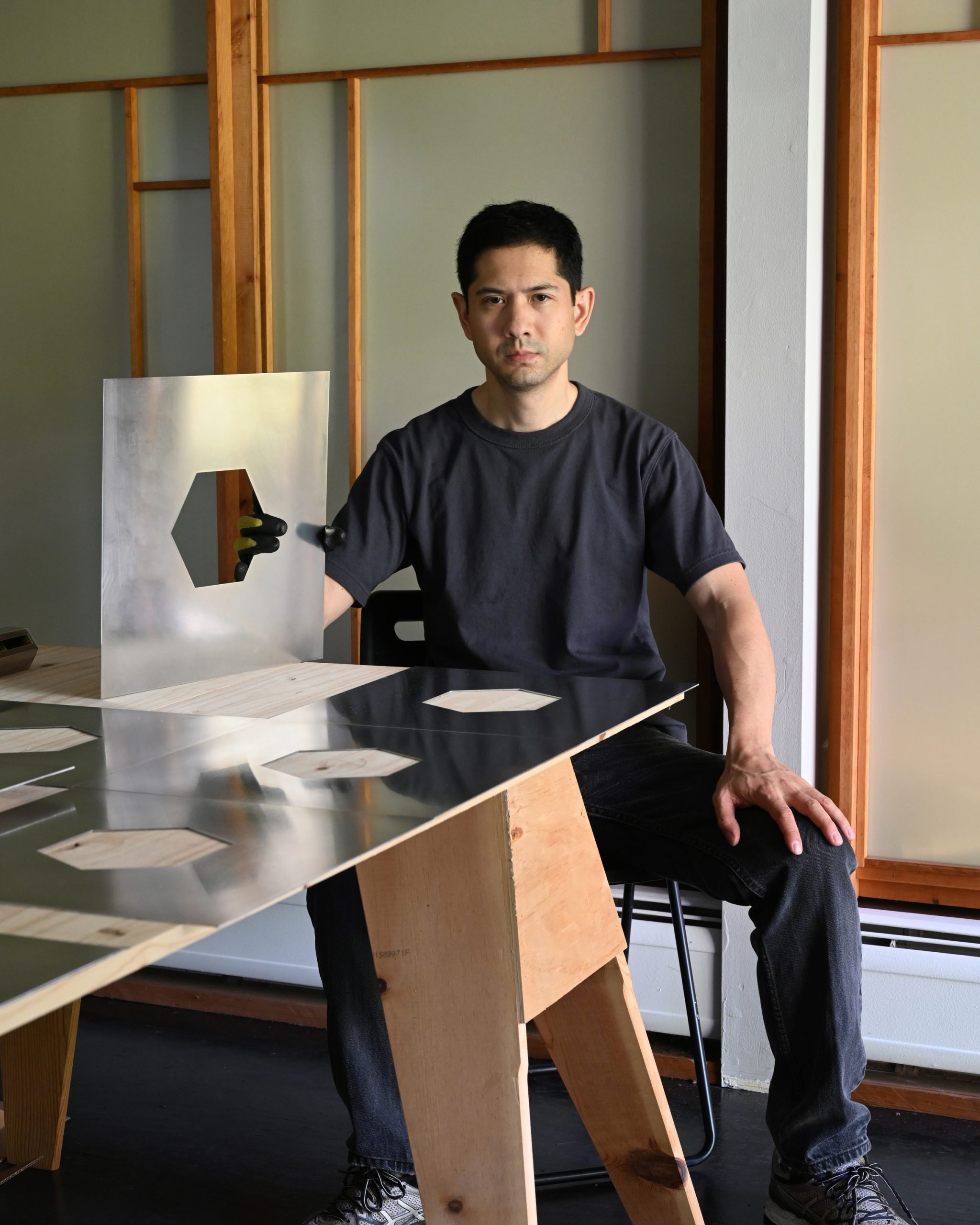

Michael Wang is an elementalist. The multi-disciplinary conceptual artist and architect has spun the ephemeral qualities of air into the tactile, toyed with the transmutational properties of water, and now, with his upcoming exhibition, “Yellow Earth,” he contemplates and displays man’s relationship to uranium, the earth’s natural source of nuclear energy.

Michael Wang, 35°33’8”N 108°36’30”W (2024). Courtesy of the artist.

“A lot of my work is related to energy,” Wang said on a video call last week. “This show is the next chapter of looking at the natural origins of modern energy.” Through his practice, Wang examines the natural world, celebrating its beauty while considering humanity’s position within—or without—it. He is drawn to the constructive and destructive capabilities of energy and its iterations. In particular, he seeks to reveal, rather than expose, the hidden truths and cycles that connect everything together. “Yellow Earth” opens Thursday and runs through August 31 at the TriBeCa gallery Bienvenu Steinberg & C.

The exhibit’s name is derived from the yellow color of refined uranium ore, the show’s central material. One of the objects on display is Collision Bar, (Three Balls)—a sleek hexagonal aluminum baton with a slit revealing three acid yellow glass marbles socketed within. The marbles’ eerie glow is at once inviting and ominous, a result of the pigmented uranium embedded within the glass. The artifact evokes the steel control rods of a nuclear reactor, a symbol of both power and danger. Other pieces in the exhibit incorporate small nuggets of slightly radioactive uranium ore. The ore samples are invisible, hidden within sculptural “containment structures” that completely block the transmission of radiation.

Michael Wang, (Left) Trinities (Fuel Cores) (2024). (Right) Yellow Painting (Tailings) (2024). Courtesy of the artist.

The show is not only a compelling meditation on the element, but also curated dialogue with the work of Walter De Maria (1935-2013), the father of Land Art (in fact, De Maria’s former lower Manhattan studio was located across the street from the gallery). “Walter De Maria was so interested in danger and its aesthetics. With this work, I am trying to activate the emotional power of his work,” Wang explained. “The muteness of De Maria’s works (and of the artist himself) erases some of the connections that I’m trying to make more visible, or more sensible.”

Wang observes an “atomic” undertone in De Maria’s oeuvre. De Maria’s formal language and his exploration of invisible energies reflect the Nuclear Age’s influence on his art. In The Vertical Earth Kilometer (1977), the precision of the artist’s interment of kilometer-long bronze rods mirrors the technical process of burying a nuclear cache for underground detonations. His iconic The Lightning Field (1977) is staged atop actual uranium reserves. Uranium mining in New Mexico, the site of the very first atomic testing, peaked the same year The Lightning Field was unveiled to the public. Wang’s work seeks to connect these dots, revealing “hidden chains of relations.” At the crux of the show is a corridor of seemingly innocuous sealed aluminum tubes. Contained within each tube are radioactive soil samples from New Mexico’s uranium mining belt.

Michael Wang, Collision Bar (Three Balls) (2024). Courtesy of the artist.

Some ideas for the show have been germinating since Wang’s youth. His father was a geophysicist. “From a scientific perspective, from a young age I learned the earth itself is a system. That gave me an awareness of some of these processes,” he said. “My own interest in art was sort of looking for these almost new tools. Natural processes to me didn’t just seem like things that could be subject matter for art making, but they were things that I might actively engage with.”

Installation view of Michael Wang, Extinct in New York (2019). Courtesy of the artist.

Within Wang’s practice, there is a palpable tension between the sensual aesthetics of the earth and the political exigencies of today’s climate. Uranium’s charged symbolism and practical impact are juxtaposed with its existence as just another earthly mineral with its own intrinsic beauty and inextricable links within the natural order, both visible and invisible. The element is not presented as inherently positive or negative, but rather, Wang lets the material hang in the ambivalence that he himself is most comfortable in. This off-to-the side neutrality, presenting scientific data to an art viewer and letting them shape their own perspective is a through line in Wang’s diverse work.

Michael Wang, Wulai azalea (Rhododendon kanehirai Wilson), Feitsui Dam and Reservoir, New Taipei City, Taiwan. Courtesy of the artist.

First exhibited at the Fondazione Prada in Milan in 2017, Wang’s long-term project Extinct in the Wild equally grapples with the ethics and emotions of ecological complexities. Wang displayed flora and fauna in greenhouse-like structures with life-support systems designed to cater to the fragile organisms’ specific needs. The exhibit’s species are no longer found in nature, due mainly to human causation, yet they continue to survive by human stewardship. Specimens included the axolotl, a salamander that today can only be found in aquariums or kept as pets. The show’s curators were trained and assigned the task of tending to the organisms. Wang reverts curation to its etymological root—cura is care—by tasking curators with caretaking.

“The ambivalence and double-edgedness of that relationship is really what drew me to the work,” Wang said.

Installation view of Michael Wang, Taihu (Stones) (2022). Courtesy of the artist.

Another of Wang’s energy-focused projects was 10000 li, 100 billion kilowatt-hours, shown at the 2021 Shanghai Biennale. He constructed a massive machine that processed water from China’s Yangtze river which runs through the largest dam in the world, the Three Gorges Dam. The machine’s high-powered jets vaporized the water, turning it into snow.

Michael Wang, 10000 li, 100 billion kilowatt-hours (一万里,一千亿千瓦时) (2021). Courtesy of the artist.

Though the city of Shanghai is subtropical, the Yangtze’s waters are sourced from a melting mountain glacier in the “third pole”, the largest existing ice reserve outside of the north and south poles. Through Wang’s work, the river’s water returned to its genesis. “Art for me isn’t just about a strictly-defined human sphere,” he said, “but extends to touch all those entities we are inextricably bound up with.”

“Yellow Earth” will run from June 27th through August 31st, 2024 at Bienvenu Steinberg and C, 35 Walker St, New York, NY 10013.