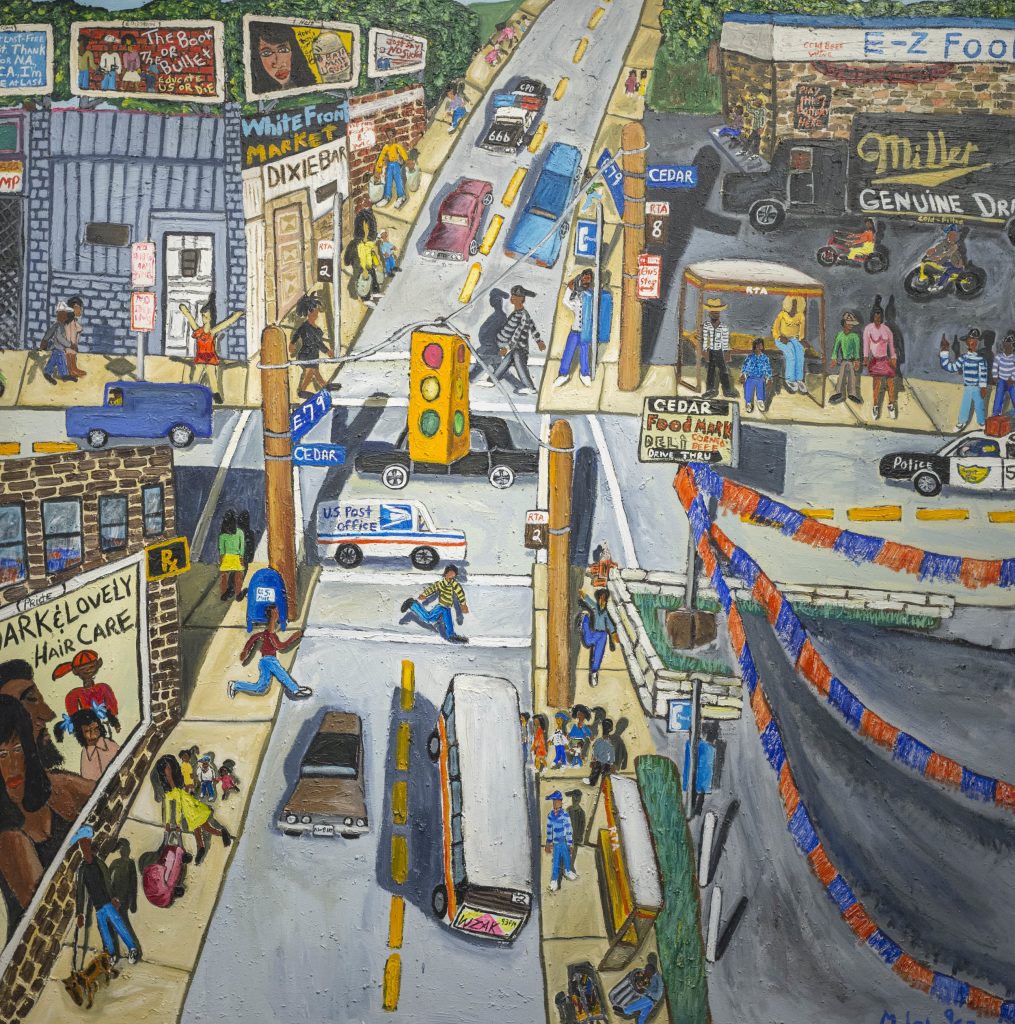

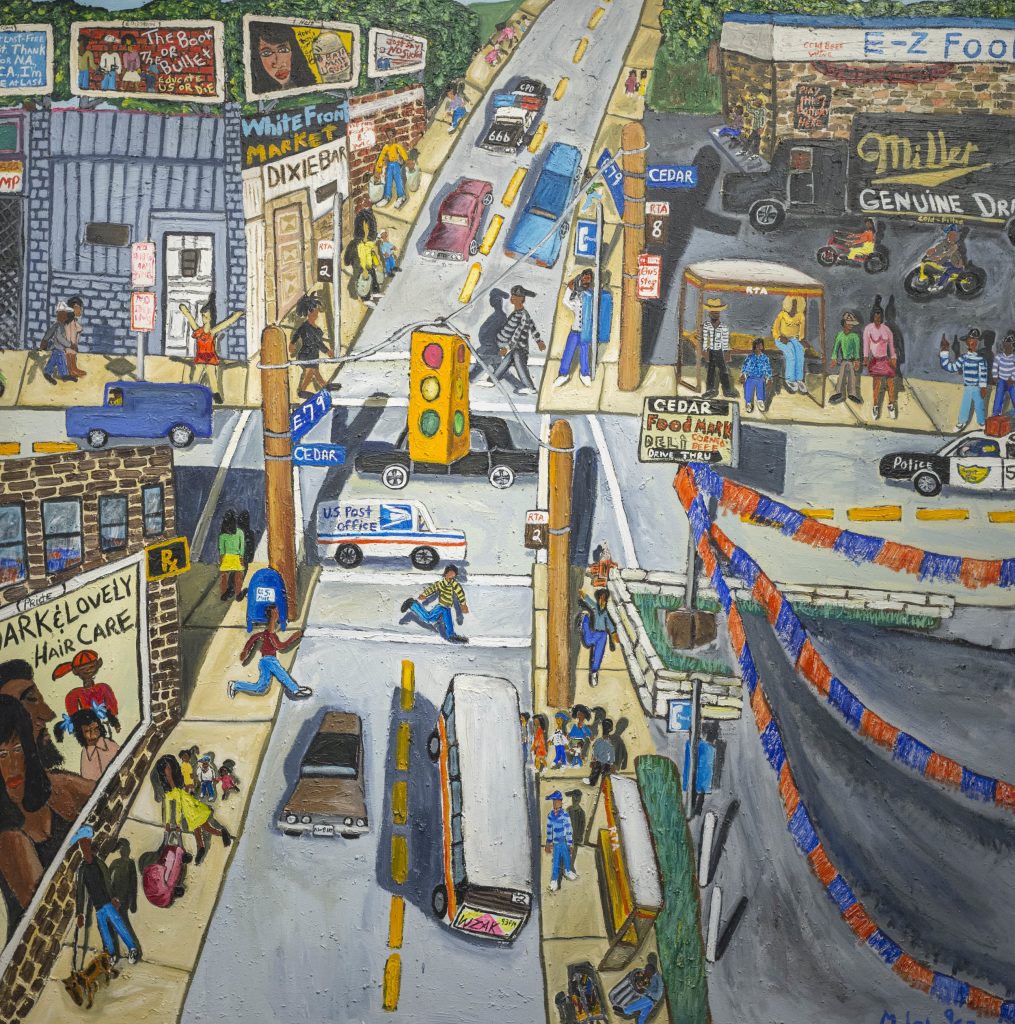

Thirty years ago, Michelangelo Lovelace began working as a nurse’s aide at a senior care facility in Cleveland, Ohio. On the side, he was making artwork—vivid, colorful paintings and sculptures depicting Cleveland from the perspectives of its inner-city inhabitants that juxtaposed the promises of the city and its particular American Dream against life in the streets.

For swaths of people, the effects of police brutality, poverty, and lack of access to education and healthcare made life, in Lovelace’s words, “fast, poor, and short”—a perilous combination he sought to illustrate in dizzying, people-packed scenes. But behind the canvas, Lovelace’s second career as a nurse’s aide was quieter and more contemplative, concerned with the stories of individuals.

Michelangelo Lovelace, At The Intersection of East 79th And Old Cedar (1997). Image courtesy Fort Gansevoort.

An online show of 22 drawings at New York’s Fort Gansevoort gallery (“Nightshift,” through July 9) pays homage to that stretch of time, when, at night, the artist would don masks, gowns, and gloves in preparation for his night shifts. While at work, he tended to patients whose health was particularly frail, and who required round-the-clock care. Many of them were Black or people of color, and over the years, the artist got to know their stories intimately, eventually convincing them to sit as his subjects.

His portraits of those sitters—sketched and drawn at their bedsides, or from discreet vantage points in common areas in pen and marker—comprise the show.

The work is especially relevant now, as it stands at the intersection of two defining moments: the coronavirus pandemic, and the resurgent Black Lives Matter movement, following the death of George Floyd. That fact is not lost on Lovelace, nor does he much mind that the show has drawn so much attention for emerging at this particular moment.

“It’s why you have to make art, for the love of it,” he says. “People are curious about this work now because of whatever circumstance is going on at this particular time in history. But that will change. So during this time, you just have to say to people, ‘Can you feel me? Can you feel what I’m saying?’ They may not like me and I’ve had people tell me they don’t get the work. But they never forgot it, either.”

Michelangelo Lovelace, Mrs. Hardwick (1993). Image courtesy Michelangelo Lovelace.

Born and raised in Cleveland, Lovelace has long been concerned with depicting forgotten or disenfranchised communities through heady, charged works wherein the message is, generally speaking, available to anyone willing to engage with it.

In an article published on the Fort Gansevoort website, the sculptor John Ahearn, who curated the show, described what makes Lovelace’s work so legible: its deep, flat surfaces, on which every detail is laid bare for the viewer. There are no dark corners into which inner-city America is relegated—these figures, their circumstances, and their lives are centered in the work, shining in the sun for all to see.

In Lovelace’s oeuvre, a kind of urgency naturally emerges, allowing all the various parts of an otherwise segregated community to spill into each other. Looking at the whole picture, it’s hard not to think about how fractured American society is and has always been, and about how its freedoms are extended to only a few, as the fates of others are ignored.

Michelangelo Lovelace, American Panther (2016). Image courtesy Fort Gansevoort.

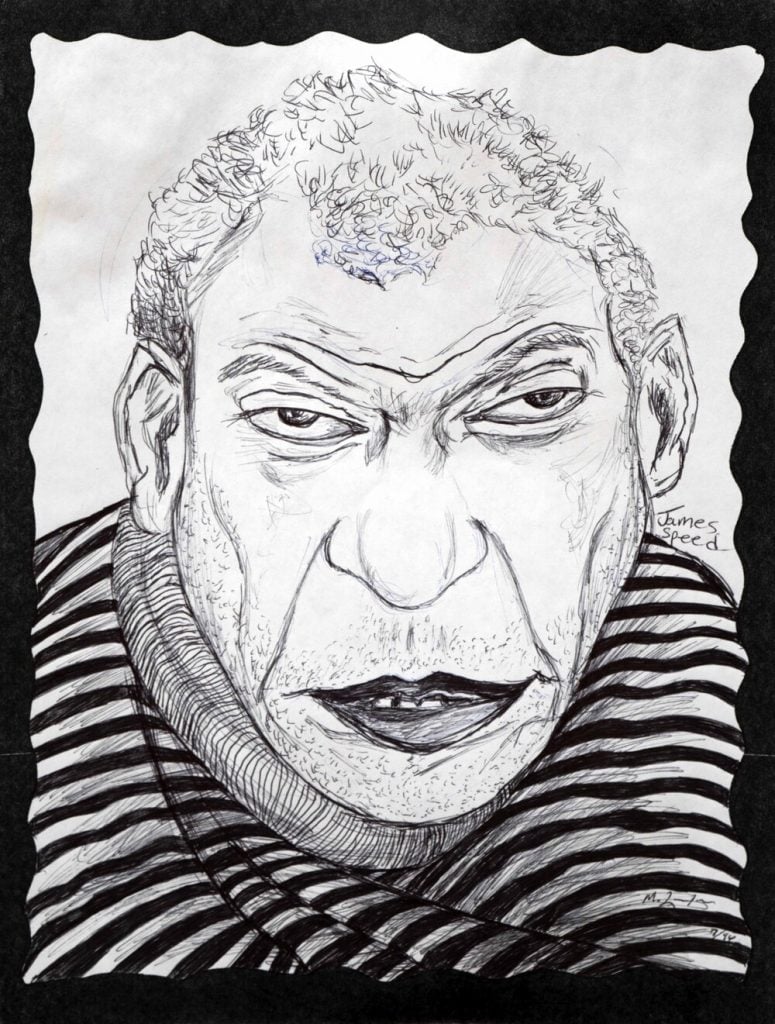

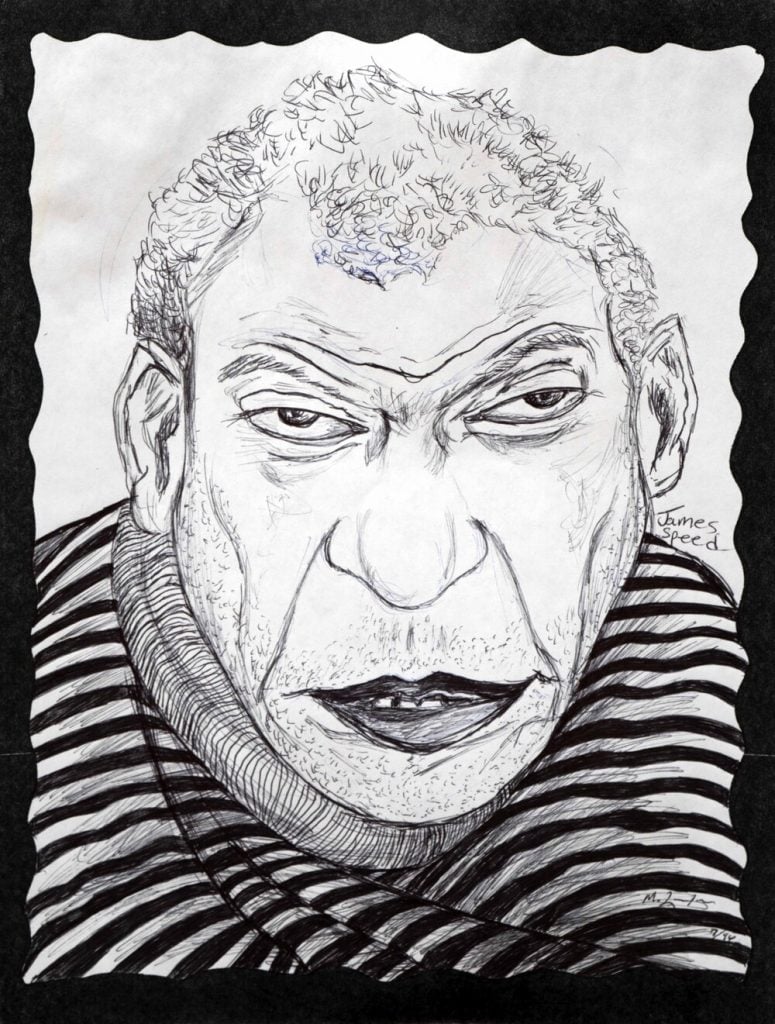

Yet while the drawings in “Nightshift” are not as overtly bold or resounding as Lovelace’s other works, they carry with them a sort of profound, quiet dignity. Each portrait is painstakingly detailed, characterized by the imprints of lives lived: worry and laugh lines, crow’s feet, and heavy eyelids housing knowing pairs of eyes. Here is napping Mrs. Hardwick, whose set but sympathetic expression drums up feeling, even while she sleeps; and there is James Speed, whose sense of style—a scarf is tied around his neck, a striped shirt just below it—offsets his glassy gaze.

“You try to find those distinct lines,” Lovelace says. “Whether it’s in the jawbone sinking in, or on the forehead or beside the eyes, they are the defining things that make these characters. They are the things that make them say ‘Okay, that looks like me.’”

Michelangelo Lovelace, James Speed (1996). Image courtesy Fort Gansevoort.

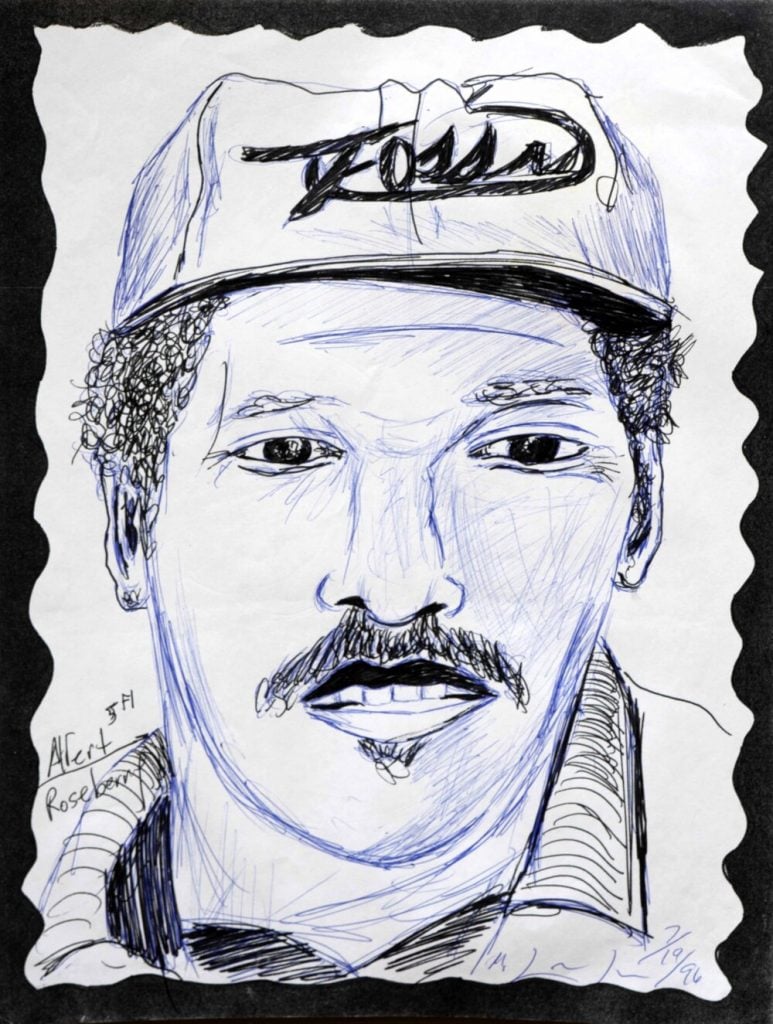

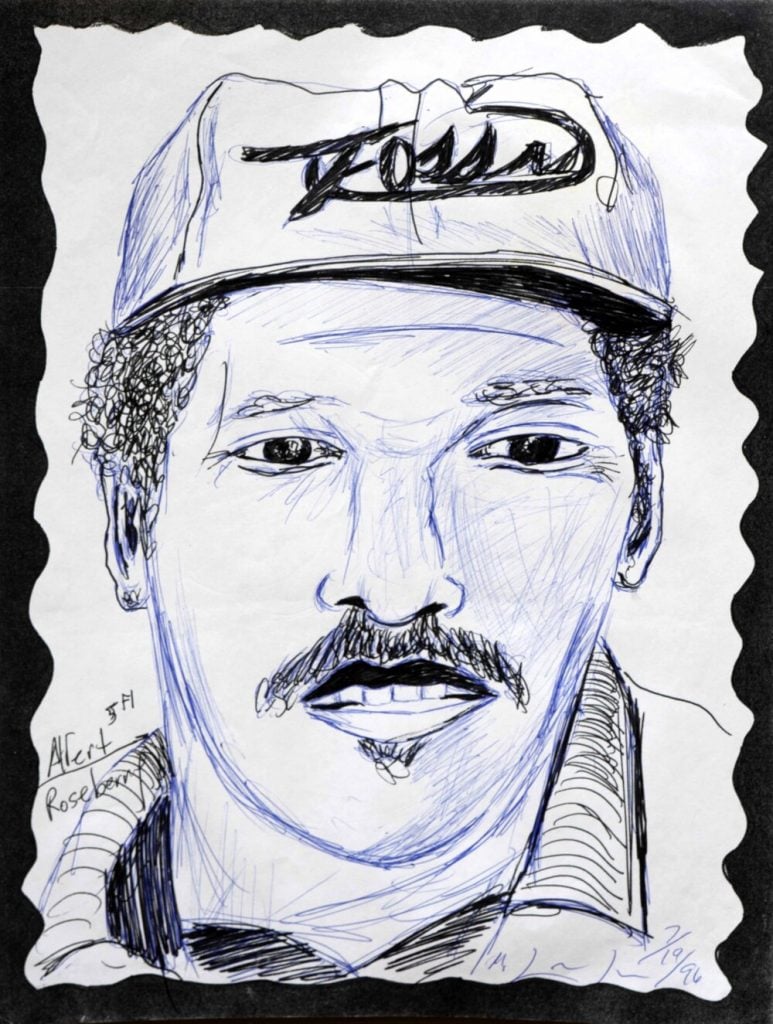

Each of the faces in the series becomes someone, brought to life by pared-down ballpoint pen or bold-strokes marker, depending on the personality.

“I think if people see this work and start to have an appreciation for the elderly… you know, anything we get to experience now, they’ve paved the way for us,” he says.

“They had lives before they were in a nursing home. They had important lives. And that’s what I learned while doing these drawings and just having general conversations with them. You know, like ‘How are you doing?’ and ‘Have you seen your wife today?’ I met a freedom rider, a lady who danced at The Cotton Club, and an ex-police officer who was one of the first Black cops in the South.”

As America reckons with its historic inability to count the lives of the forgotten—at the center of which, now and before, are the elderly and Black communities—Lovelace’s art feels inherently instructive. To observe every portrait 20 years after its making, is to be reminded of everything we’ve missed—and all the work still left to be done.

Michelangelo Lovelace, Albert Roseberry (1996). Image courtesy Fort Gansevoort.

The nursing home where the artist last worked (up until just this past winter) was recently converted into a COVID-19 patient-care unit.

“It’s funny to imagine that’s where I’d be if I were still working there,” he says. “But every generation’s got to fight their fight. Every few years, something’s going to rear its ugly head. You know, the more things change, the more they stay the same. But we have to remember that everything going on is not a Black issue or an older person’s issue. It’s all human rights issues. We need to remember the faces—and the lives on the line.”