Art & Exhibitions

What Mierle Laderman Ukeles’s ‘Maintenance Art’ Can Still Teach Us Today

The Queens Museum is presenting a retrospective of the influential feminist artist.

The Queens Museum is presenting a retrospective of the influential feminist artist.

Ben Davis

The Queens Museum is devoting more space than it has ever given over to a single artist to survey the career of Mierle Laderman Ukeles (1939–), a pioneer of community-engaged art whose work chimes with that institution’s own community-building ethos.

For her celebrated Maintenance Art Manifesto alone, Ukeles deserves the honor.

That razor-sharp text was written in 1969 by a 30-year-old recent mother and not-yet-famous artist in an afternoon of frustration. It welds together Conceptualism and feminism into one rhetorically explosive statement of purpose.

In its various galleries, the Queens Museum show ranges from Ukeles’s early, fairly unsightly work with knotted cheesecloth, rags, and newspaper, through copious photo and text documentation of the mature public performances for which she is best known—most famously as a part of her multi-decade-long, unpaid artist residency for the New York Department of Sanitation—to her more recent, less convincing experiments in landscape design at the former landfill in Fresh Kills, Staten Island, and elsewhere.

Mierle Ukeles Laderman’s early Second Binding (1964), installed at the Queens Museum. Image: Ben Davis.

Still, the “Maintenance Art Manifesto”—displayed here in a frame—is the nodal point that everything flows into or out of. What led up to it?

One influence on the writing of that text was the palpable scorn of colleagues who treated her as invisible once she became a mom. That has been an oft-told part of her story, capturing the external pressures of sexism. But the internal pressure on display in the gallery is that of her own titanic creative ambition.

After quitting her studies at Pratt, Ukeles had been toying with the idea of giant, inflatable sculptures. Her concept drawings for these envision parades of people in groovy inflatable suits or snake-like pneumatic structures engulfing skyscrapers. But imagining such follies was easy; constructing them so that they were actually durable proved impossible.

One of Ukeles’s concept sketches for inflatable art. Image: Ben Davis.

This fed into the core idea of Ukeles’s manifesto: that “maintenance” was as important as creation itself.

Ukeles’s text opposed two modes of thinking: creation, coded as male, and highly valued; and maintenance, coded as female, and devalued. From that point on, she declared that her mission would be to value the processes of maintenance—both her own domestic work of childcare and housework, and the low-wage labor that kept the whole economic system turning over—and name it “Maintenance Art.” And so she has.

The most memorable parts of Ukeles’s work are the ones that hew closest to this simple, powerful insight. Most famously, this yielded works like the performance Hartford Wash (1973), documented in black-and-white photos, for which the artist simply performs the act of washing the floors of the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, forcing attention to the value of the unglamorous work that makes the museum function by reframing it as performance art.

Intellectually, the concerns of the Maintenance Art Manifesto were very much of a piece with the era’s larger feminist ferment. To take one example, at the same time that Ukeles was scrubbing the floors of the Atheneum, another radical demand for recognition of domestic labor, the Wages for Housework movement, was just beginning to fire the imagination of activists, arguing that uncompensated labor in the home was the foundation of the economy, and therefore ought to be rewarded.

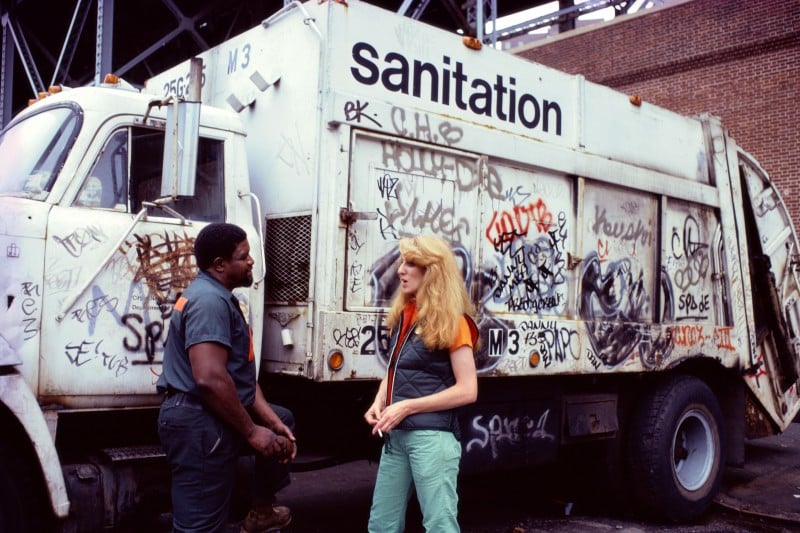

Mierle Ukeles Laderman at the press conference for her Queens Museum show. Image: Ben Davis.

But Wages for Housework emerged out of debates within Italian Marxism, whereas Ukeles’s Maintenance Art emerged out of the artist’s devout Judaism (she is the daughter of an Orthodox rabbi, after all). Thus, while one Wages for Housework proposal was that housewives perform the necessary work of the home but treat it like alienated labor (“More smiles? More money!“), Ukeles’s move was in the other direction, bestowing the sacralizing aura of art on domestic routine.

For a work at New York’s A.I.R. gallery in 1974, she would scrub the sidewalk as a public performance. To explain the meaning of that action, she posted a long, mystical quote that read, in part, “The face of the holy is not turned away from but towards the profane,” from Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook (the father of religious Zionism).

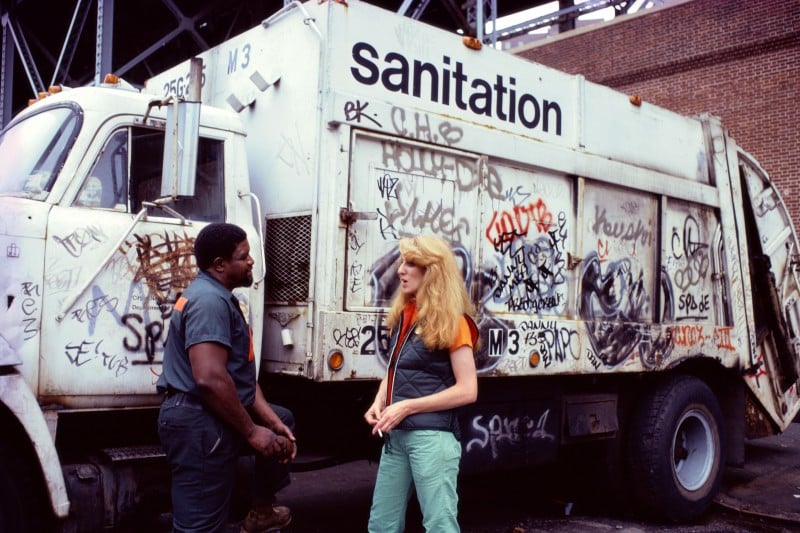

Distinct in inspiration, Wages for Housework and Maintenance Art were also opposite in trajectory: The former brought the language of workplace struggle to the domestic sphere; the latter took Ukeles’s spiritual redemption of housework into the workplace. The most well-known example is her year-long project with the New York Department of Sanitation, Touch Sanitation (July 1979-June 1980).

The idea was both simple and immense: Amid New York’s brutal 1970s fiscal crisis, which had led to layoffs, cut backs, and demoralization among city workers, the artist vowed to shake the hand and thank all 8,500 “sanmen” (sanitation workers, all at that time men) in the city. In the document outlining her pitch, Ukeles wrote that she wanted to bring a bit of “Artmagic” to the city bureaucracy.

Documentation of Touch Sanitation at the Queens Museum. Image: Ben Davis.

At the museum, the walls of color photos of Ukeles making her 10 “sweeps” through the city show the cheerfully hip figure she cut against the background of NYC’s disrepair. An accompanying documentary gives a humanizing record of the frustrations of her subjects; conditions were so dire, amid the ‘70s austerity drive, that the furniture in their break rooms was scavenged from the street.

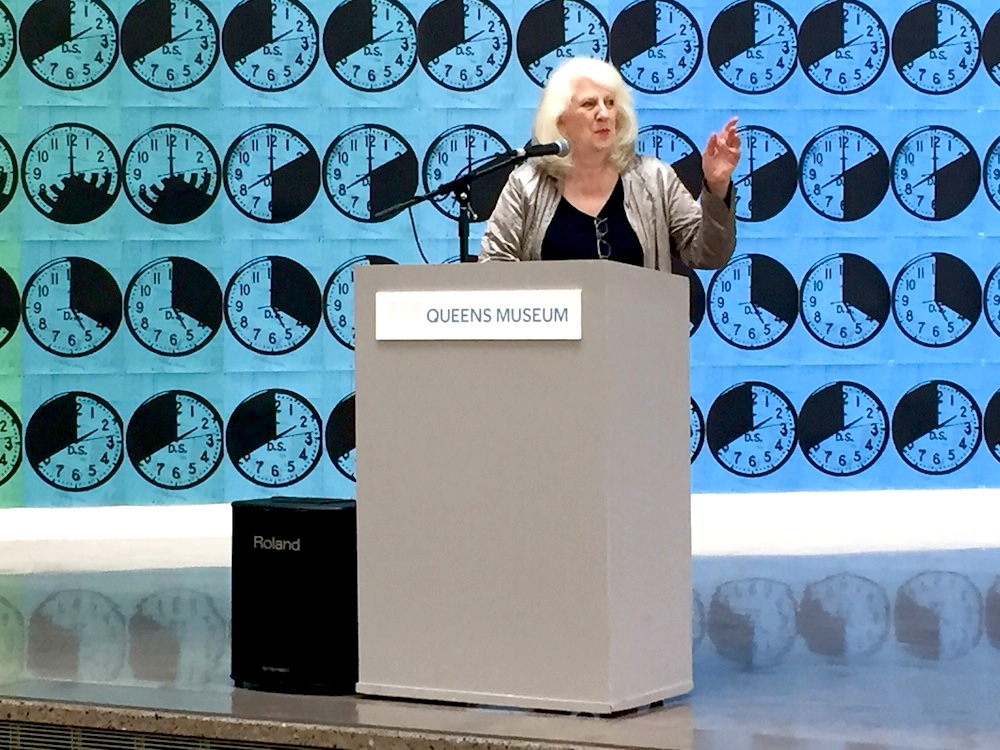

Touch Sanitation provided a feel-good story for a tough time in New York’s civic life, and received lots of bemused coverage, as well as some predictable attacks of the “you call this art??” variety, zeroing in on the supposed misuse of NEA funding. (A highlight of the Queens show is a book of press clippings, where Ukeles herself has furiously annotated each piece of bad press.)

Press clipping about Touch Sanitation as annotated by Mierle Laderman Ukeles. Image: Ben Davis.

The truth was, though, in its redemptive voluntarism, Touch Sanitation was a piece of Conceptual art that bureaucrats could wholeheartedly love. Even mayor Ed Koch, who had attacked the unions as spoiled, took time out to salute Ukeles’s celebration of union labor.

“Seriously, who’s to deny that friendly exchange and contact between human beings is not the greatest of all arts?,” the pugnacious mayor effused in a 1980 letter. “Accordingly, may you continue to ‘shake up’ our City for many years to come.”

The careers of the experimental-art giants of the ‘60s and ‘70s have often followed a common pattern. Artists tended to bootstrap themselves to prominence via the publicity of some outrageous anti-art gesture, then spend the rest of their careers evolving more and more decorative versions of that theme.

Thus, Richard Serra, once known for slinging around formless ribbons of hot lead, now specializes in the most inoffensively awesome public art; Joseph Kosuth, who once proposed pure idea as art, now does neon labyrinths of philosophical catchphrases; and so on.

So it has been with Ukeles. The themes of Touch Sanitation would morph into a series of Work Ballets, for which she marshals municipal workers to parade their vehicles in choreographed formation, an idea she has now staged in cities all over the world. These are lovable, though they do evoke the slight silliness of the Soviet-era romance of the tractor.

Installation view of Ceremonial Arch Honoring Service Workers at the Queens Museum. Image: Ben Davis.

The same tinge of corniness holds for the literal centerpiece of the Queens show, occupying the core of the museum: Ceremonial Arch Honoring Service Workers, a structure with each of its pillars made of tools representing a different city department, pediment formed of a massive accumulation of work gloves.

These are both big-hearted celebrations of the dignity of labor that is overlooked and undervalued. You have to say, though, that compared to the minimalist performance-art rituals Hartford Wash and Touch Sanitation, they represent returns to more conventional ideas of civic pageantry and monumental sculpture.

What is the legacy of “Maintenance Art,” almost a half century on? Ukeles’s work with the New York Department of Sanitation has become the template for government agencies everywhere looking for a little good PR through artistic collaborations, with all the potential benefits and compromises that implies.

Yet her impact there may be less extraordinary than her sudden cachet in an industry whose values, outwardly, represents the antithesis of unglamorous, necessary routine work that Ukeles set out to celebrate in her “Manifesto:” fashion.

During last week’s New York Fashion Week, a young designer who has worked with Kanye West, Heron Preston, got scads of press for a new line of Department of Sanitation-themed haute-couture streetware directly inspired by “Maintenance Art.” Ukeles’s Social Mirror—a mirror-clad garbage truck she debuted in 1983 in the long wake of Touch Sanitation—even made an appearance in advance of its trip to the Queens Museum for the retrospective.

Last week at @heronpreston's #DSNY show! Great evening for a great cause! Never saw such a sleek sanitation vehicle pic.twitter.com/qDDLiRrFbE

— Claudia Mason (@ClaudiaMason1) September 14, 2016

On one hand, the idea of $1,200 purses made from upcycled safety vests quite literally represents the logical final step in “valorizing” maintenance work (some of the proceeds go to a newly formed city foundation that ultimately will create a New York Department of Sanitation museum). On the other, it represents the pitfalls lurking somewhere in the background, the gesture emptied out in fashion’s contemporary quest for symbolic “realness.”

In one of the most frequently quoted lines of her “Manifesto,” Ukeles sums up her interest: “The sourball of every revolution: after the revolution, who’s going to pick up the garbage on Monday?” The New Yorker account of the Heron Preston launch ends with the attendant “fashion people,” disappointed by a Kanye-and-Kim no-show, leaving behind a mess for the sanitation workers to clean up.

Ukeles has often described how Maintenance Art Manifesto was written in a fit of “cold fury.” Even as her work gets a much-deserved canonization, it seems to me that this original, angry impulse is still very much in need of maintenance.

“Mierle Laderman Ukeles: Maintenance Art” is on view at the Queens Museum, September 18, 2016-February 19, 2017.