Law & Politics

An Italian Court Demands the Restitution of an Ancient Roman Lance Bearer From the Minneapolis Institute of Art

The famed copy of one of the most famous classical Greek sculptures was purchased for $2.5 million.

The famed copy of one of the most famous classical Greek sculptures was purchased for $2.5 million.

Sarah Cascone

The Torre Annunziata court near Naples, Italy, has ruled that the Minneapolis Institute of Art must restitute an ancient statue that the government claims was illegally excavated in the 1970s. The museum bought it in 1986 for $2.5 million.

“We have seen press reports that a court in Naples, Italy, has called for the return of a work of art in the museum’s permanent collection,” a museum spokesperson told Artnet News in an email. “We have not been contacted by the Italian authorities in connection with the court’s decision. If the museum is contacted, we will review the matter and respond accordingly.”

Gaetano Cimmino, the mayor of Castellammare di Stabia in the south of Naples, where the statue is believed to have originated, is calling on Italian Minister of Culture Dario Franceschini to secure the artwork’s return. The hope, reports the Cronache della Campania, is for its eventual display at the town’s Archaeological Museum of Stabia Libero D’Orsi, which opened in the fall of 2020.

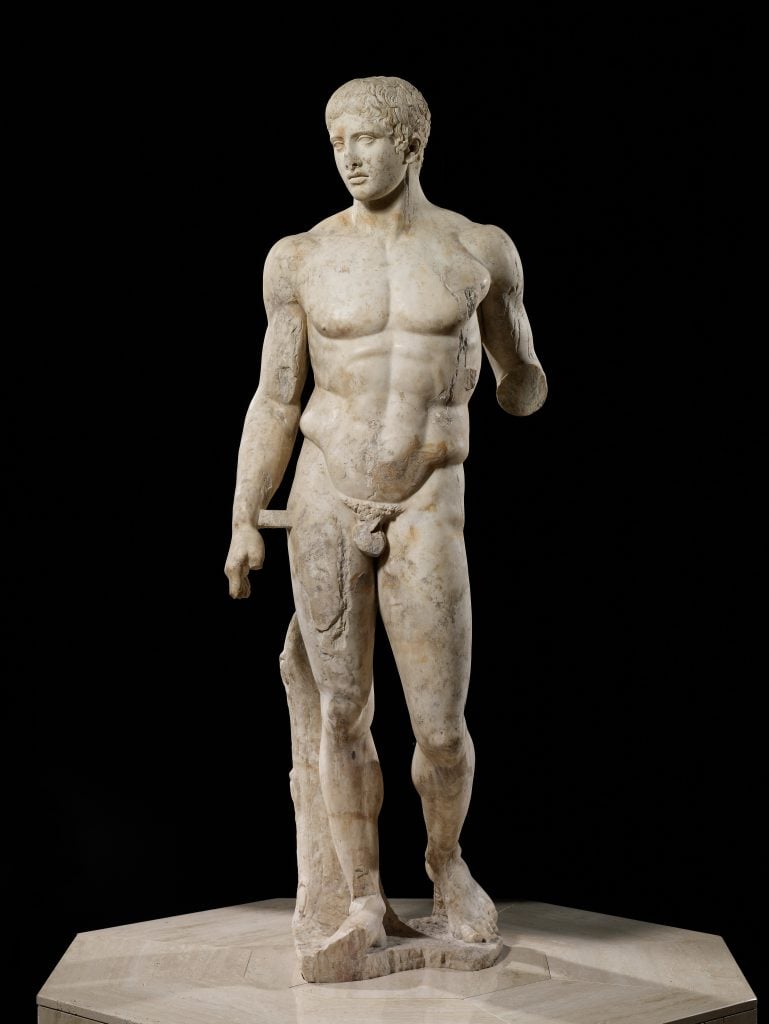

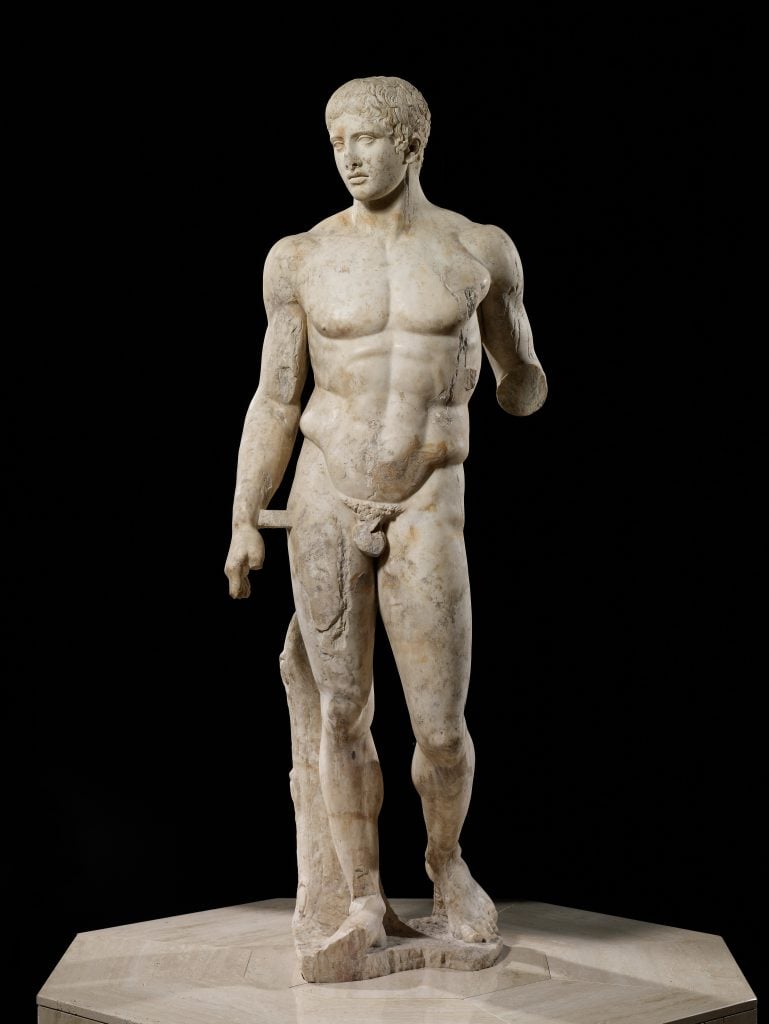

The statue is one of only a handful of extent Roman copies of the Doryphoros (or lance bearer), one of the most famous classical Greek sculptures. Created by the fifth century B.C. artist Polykleitos, the six-foot-six male nude is meant to embody the ideal body, and is an early example of contrapposto sculpture. (In a lost treatise, the artist wrote a canon about the principle of symmetria and how to mathematically calculate perfect proportions, possibly using the tip of the pinky finger as a base unit of measurement.)

The Villa Arianna, Roman ruins from the Archaeological Museum of Stabia Libero D’Orsi in Castellammare di Stabia. Photo courtesy of the Archaeological Museum of Stabia Libero D’Orsi.

Archaeologists excavated two copies of Doryphoros that are now at the Naples National Archaeological Museum at Herculaneum and Pompeii, two towns destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in the year 79. Another copy of the statue surfaced in 2012, in the ruins of an ancient Roman bathhouse in southern Spain. A partial torso is in the collection of the Uffizi in Florence.

The contested MIA statue, made in the first century BC, is among the best preserved of the bunch, missing only its left arm. But its provenance is murky.

A text apparently originally written by the MIA shared on a website hosting 3-D printing files notes that “the museum’s Doryphoros has been known to scholars since the early 1970s,” while Wikipedia suggests that the MIA maintains that the work “was found in Italian waters during the 1930s and spent several decades in private Italian, Swiss and Canadian collections before resurfacing in the art market around 1980.”

The Minneapolis Institute of Art in 2018. Photo by McGhiever, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

According to Italy, the truth is that looters illegally excavated the fragments of the ancient work in 1976, and sold the sculpture for about 100 million lire ($1.2 million) to Basel antiques dealer Elie Borowski, known for trafficking stolen works of art.

In the early ’80s, the artwork is then believed to have gone on view at the Glyptothek of the Antikenen Museum in Munich, where the Naples Public Prosecutor’s Office caught wind of the illicit object, according to the Archaeology News Network. But even though Italy pushed Germany to seize the work at that time, the Bavarian Court of Appeal released it in 1984. The statue slipped through the nation’s fingers and Borowski was able to sell it to the MIA.

The artwork’s movements were investigated by the Carabinieri of the Naples Cultural Heritage Protection Unit, the Torre Annunziata Group’s investigative unit, and the Public Prosecutor’s Office.

Gabriel Zuchtriegel, director of the Pompeii Archaeological Park, was able to confirm that the work in Minneapolis was the same one stolen back in 1976 by emailing with the museum and determining that both statues were missing the right foot and a finger on the right hand, reports Positano News.