Art World

This Small Minnesota College Thinks It Owns a Munch—and New Evidence Backs It Up. But Oslo’s Munch Museum Is Keeping Mum

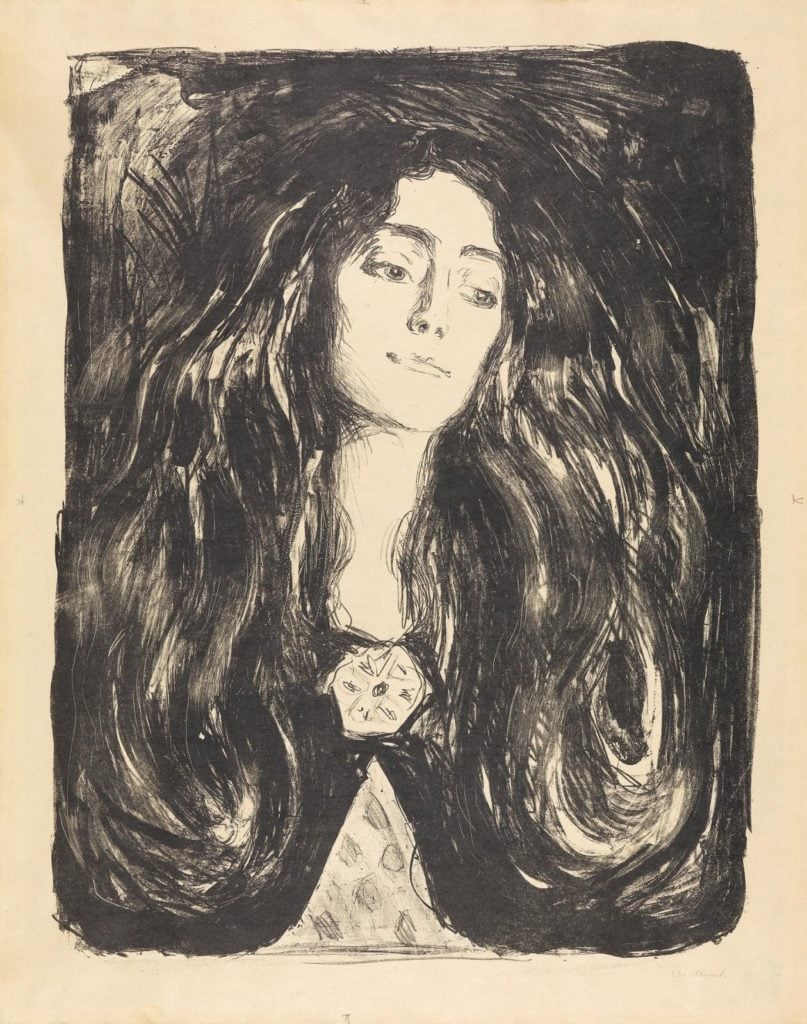

The painting seems to depict Munch's one-time lover, violinist Eva Mudocci.

The painting seems to depict Munch's one-time lover, violinist Eva Mudocci.

Sarah Cascone

An unfinished portrait donated to St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minnesota, in 1999 could be a long lost painting by the great Norwegian artist Edvard Munch.

A recent study of the painting’s provenance and a scientific analysis of the materials used give credence to the attribution. But now it’s up to the Munch Museum in Oslo to have the final say—and they’re not talking. A spokesperson for the institution told the Wall Street Journal that museum staff are too busy preparing for a move into a new building to provide authentication services.

The painting, believed to be a portrait of violinist Eva Mudocci, was among more than 2,000 works donated to St. Olaf’s Flaten Art Museum by Richard Tetlie, a 1943 graduate of the college. Munch was romantically involved with Mudocci for a brief period beginning in 1903 did three known lithographic portraits of her. But the two split abruptly in 1904, which could explain why the painting is unfinished.

There had long been rumors that St. Olaf’s painting was by Munch, in part because the Los Angeles County Museum of Art displayed it as such in the 1960s and ’70s. But it wasn’t until Mudocci scholar Rima Shore took an interest in the work that anyone was able to determine its provenance.

Edvard Munch,The Brooch. Eva Mudocci (1903). Photo courtesy of Nasjonalmuseet/Dag A. Ivarsøy.

While researching her new book Lady With a Brooch: Violinist Eva Mudocci—A Biography and a Detective Story, Shore found letters Munch wrote speaking of a visit to Mudocci in late 1903 and early 1904, and of his plans to paint her. Another letter, from a collector to Munch, asks how his painting of a female violinist is going.

Shore also tracked down an auction record from 1959 showing that Poul Rée had purchased the work in Copenhagen from the estate of Danish illustrator Kay Nielsen, a close friend of Mudocci’s. In a letter, Harald Holst Halvorsen, a prominent Munch dealer, offered to authenticate the work, but Rée declined and sold it for $10,000 to Tetlie.

Jennifer Mass of Scientific Analysis of Fine Art, Flaten Art Museum director Jane Becker Nelson, and Flaten Art Museum collections specialist Mona Weselmann examine records that have helped establish the provenance of the painting. Photo by Will Cipos for the Flaten Museum of Art at St. Olaf’s College.

After discovering this evidence, St. Olaf’s invited conservation science experts from Scientific Analysis of Fine Art to the campus last October to examine the work. Based on microscopic samples, the findings were promising.

“All of the pigments, preparation layers, and binders inferred or identified here are found in the works by Edvard Munch,” the report said. The canvas includes, for instance, strontium yellow, which was used around the turn of the century, as well as other pigments such as vermillion, Prussian blue, and cobalt blue, that appear in known Munch works from the period.

“While such materials alone cannot be considered a ‘fingerprint’ for a specific artist, they provide compelling evidence that calls for the further study of this painting,” scientific analyst Jennifer Mass told St. Olaf’s.

Specialists from the Flaten Art Museum and Scientific Analysis of Fine Art examined the canvas edge of Portrait of Eva Mudocci, attributed to Edvard Munch. Photo by Will Cipos for the Flaten Museum of Art at St. Olaf’s College.

Since publicizing their possible masterpiece, St. Olaf’s has heard from Mudocci’s granddaughter, who says that her family has always believed the painting to be a Munch portrait of the violinist.

One of Munch’s paintings of Mudocci, The Brooch: Eva Mudocci, sold at auction for $288,166 in 2014, according to the artnet Price Database. Munch’s auction record is $119.9 million, set in 2012 with the sale of The Scream to collector Leon Black at Sotheby’s New York.

St. Olaf’s asked now retired senior curator Gerd Woll to authenticate the painting back in 2004. She never did, but she has since seen the work in person, and says she isn’t convinced. “Unless some new documentary evidence proves differently, I still doubt very much that this portrait was painted by Munch,” she told the Wall Street Journal.

Flaten Art Museum Director Jane Becker Nelson with Portrait of Eva Mudocci, attributed to Edvard Munch. Photo by Sarah Hansen for Museum of Art at St. Olaf’s College.

Increasingly, it is harder and harder to get possible historical works of art authenticated, due in part to fear of lawsuits from clients who are unhappy with the results. Neither the Andy Warhol or Jean-Michel Basquiat estates offer authentication services anymore.

The Munch Museum may feel the same. “No museum wants to get entangled in a legal throw-down when there’s no upside for them,” Flaten Art Museum director Jane Becker Nelson told the Journal, “but we’re trying to make an art-historical discovery here that could be amazing.”