People

‘I Shift Into Emergency Mode Pretty Easily’: Miranda July on How to Handle the Creative Obstacles—and Opportunities—of Quarantine

July says it's time to take our digital "tools of distraction" and put them to creative use.

July says it's time to take our digital "tools of distraction" and put them to creative use.

Naomi Rea

This was meant to be Miranda July’s big year.

Yes, she’s a multidisciplinary artist known for holding down several gigs at once. But this was supposed to be a landmark year. July has just released a monograph, fittingly titled Miranda July, and her most ambitious film to date, Kajillionaire, is ready for lift off. She is also getting renewed recognition for past accomplishments, as her first feature-length film, Me and You and Everyone We Know from 2005, is being added to the Criterion Collection next week. The 46-year-old artist-filmmaker-writer was looking forward to a busy year of travel and publicity.

Speaking to Artnet News from her studio in Los Angeles, July says she is still getting used to the rituals of our new reality, and is trying to organize her priorities. “When it’s not my shift to teach second grade to my child, I’m here trying to work,” she says.

While she sounds a little crestfallen, she tells me she is as mentally prepared as ever.

“I think I am the kind of person who shifts into emergency mode pretty easily,” she says. “Maybe a little too easily for regular civilian life.”

On top of everything else, July somehow managed to organize an impromptu international arts festival from quarantine.

She came up with the idea for the Covid International Arts Festival and made a call for submissions last month, which doubled as a way for her to let her Instagram followers know she was looking at them, too.

In the first couple of hours after her announcement, just a few artworks trickled in. But by the time the 24-hour submission window had closed, she had hundreds of works to sift through, sent in from cities as far apart as Hertfordshire and Istanbul.

“It was pretty wild going through them,” she says, adding that it reminded her of the work she did setting up Joanie 4 Jackie, a Portland-based distribution network for films made by women, when she was living in the city in her 20s. (The Getty Research Institute acquired Joanie 4 Jackie’s entire 300-video archive in 2017).

“The joy of discovering someone else’s work and looking at each submission, that was a very familiar and comforting feeling,” July says—especially considering the extreme present circumstances.

“When you think in terms of your creative process, what does it mean to make anything when you are in a state of shock, and you know your audience is too?” July has since teased a follow-up edition of the festival for a later phase of quarantine.

Two recurring themes in July’s work have been finding interesting ways to connect with people, and using the internet as a tool of community-building.

Possibly her best known artwork, Learning to Love You More, was a website and exhibitions series in which she uploaded artworks made by the general public in response to prompts created by herself and collaborator Harrell Fletcher.

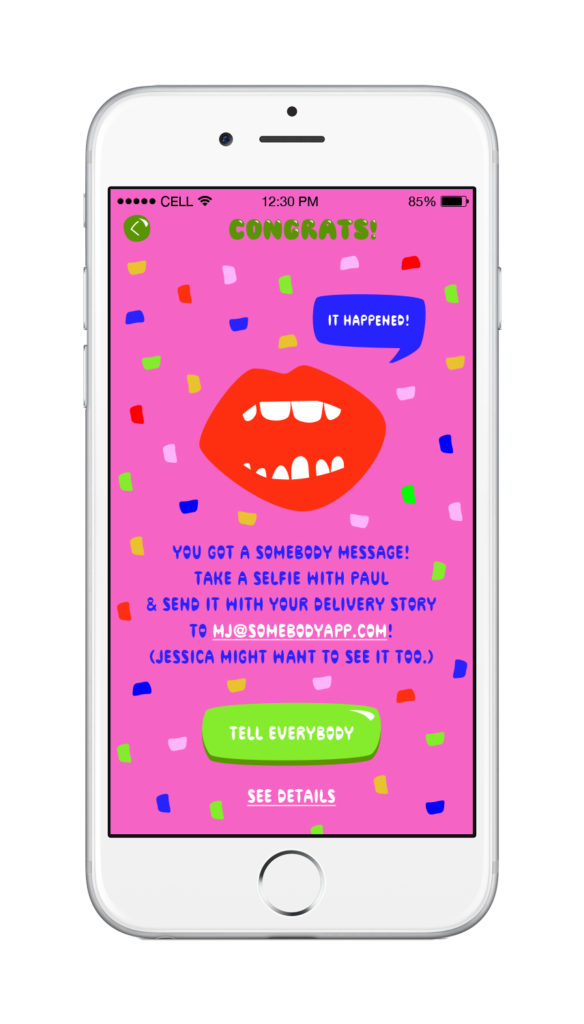

The seven-year project, launched in 2000, broke new ground in the early days of the internet art, and SFMOMA acquired it for its permanent collection in 2007. Then, in 2014, July created a messaging app titled Somebody, where chats between friends were sent to surrogate strangers, who acted as intermediaries and delivered the messages verbally.

SOMEBODY. Courtesy Miranda July.

Both Learning to Love You More and Somebody are included in July’s self-titled monograph, which was released on April 14. The mid-career retrospective looks back at 25 years’ worth of art projects, films, and books, peppered with interjections and anecdotes from July’s friends and collaborators, including Hans Ulrich Obrist and Lena Dunham.

“It’s not just a list of works,” July says. “It’s all the work and relationships and wrong turns behind all that work. And that’s half a life, right there.”

July has just finished making the biggest, most expensive movie of her career. Kajillionaire, which premiered at Sundance, is an absurdist comedy-drama that follows a family of scam artists played by an all-star cast including Evan Rachel Wood. It was scheduled for theatrical release in June, but like many other things, has now been pushed back to a yet-to-be-determined date.

Meanwhile, the Criterion Collection is giving July the ultimate indie seal of approval by reissuing her 2005 film, Me and You and Everyone We Know, on April 28. The release will include a new documentary about July’s interfaith charity shop, which she created in collaboration with Artangel in 2017.

But despite July’s seeming ability to do whatever she wants with whatever she needs, she still has an attachment to the virtue of resourcefulness.

“There are always real limitations—of money or time or energy—and then those eventually develop into almost a creative practice,” July says.

Miranda July, Me and You and Everyone We Know (2005). Still courtesy Criterion.

Right after Kajillionaire, she made an utterly captivating reality series with the actress and dancer Margaret Qualley that unfolded on their Instagram pages, which could have been done in quarantine.

“There were already limitations before this one, and I think that’s something I have in common with everyone,” she says. “But when you make something, you’re trying to dig down to a very elemental, human current that runs through all of us emotionally.”

While at home, the artist is currently working on three different projects in three different media. “I noticed that, kind of weirdly, they would seem to have been created for quarantine,” she says. “They would seem already to be alternative ways of making things, if your circumstances were incredibly limited, but they were actually pre-quarantine ideas.”

And even though many people around the world are still paralyzed by shock and grief, July sees scope for creativity and connection.

“I think we will see that we have a ridiculous wealth of tools for creating and connecting, and now they have a reason,” she says. “Now we can put them to use for something other than distraction.”