Archaeology & History

The Enduring Mystery of Easter Island’s Statues

The iconic Moai works continue to fascinate researchers.

The iconic Moai works continue to fascinate researchers.

Tim Brinkhof

Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen has an exquisite track record, having “discovered” both the Polynesian islands of Bora Bora and Maupiti. However, it’s his accounts of Easter Island for which he is most often remembered today. Similar to Christopher Columbus’ voyage to the Americas, Roggeveen stumbled upon Easter Island by accident while searching for the legendary lost continent of Zuidland, naming the island after the day on which he arrived: Easter.

When Roggeveen arrived in 1722, the Rapa Nui culture inhabiting it was already in decline—at least, according to archaeologists. Still, remnants of their former glory remained in the form of head-shaped statues (called moai) scattered across the island’s shore.

One of the charred moai statues following a serious fire on Easter Island started on October 3, 2022. Photo courtesy of the Rapa Nui Municipality.

These moai may not be as old as other famous monoliths, like Stonehenge, but they’re nearly as heavy. Pair this with the islands’ remoteness—1,000 miles from Polynesia, 1,400 miles from South America—not to mention the limited resources and technologies available to its inhabitants, and one is inevitably left wondering: How exactly were they built?

To say that these have an iconic appearance would be an understatement. Their broad, sloping noses, furrowed brows, sunken eye sockets, and protruding chins have become instantly recognizable to people from across the globe.

Equally interesting are their physical properties. The average moai statue measures 13 feet (although the largest reaches a whopping 70 feet) and weighs up to 14 tons, or roughly twice as heavy as a full-grown African elephant.

An excavated statue on Easter Island. Photo by Greg Downing, courtesy of the Easter Island Statue Project.

While we don’t know how Easter Island’s moai were made, we all but certainly know who made them. Comparing languages, mythology, and art, the scholarly community believes the Rapa Nui people originally came from Polynesia, traveling to Easter Island between 400 and 800 B.C.E. Their societal structure was likely similar to that of other Polynesian cultures, with commoners submitting to the will of a hereditary line of chiefs, or ariki.

Scholars believe construction of the moai began around 1,200 C.E. and lasted until 1650 C.E, shortly before the arrival of Roggeveen. The statues are made of soft volcanic tuff, which the islanders probably retrieved from a now-extinct volcanic crater called Rano Raraku.

According to an article published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which holds a large collection of Polynesian art and artefacts, it would have taken at least 15 people to remove large blocks of tuff from the crater. These blocks were then carved by skilled craftsmen and their assistants, with the former outlining the general shape and the latter filling in the details.

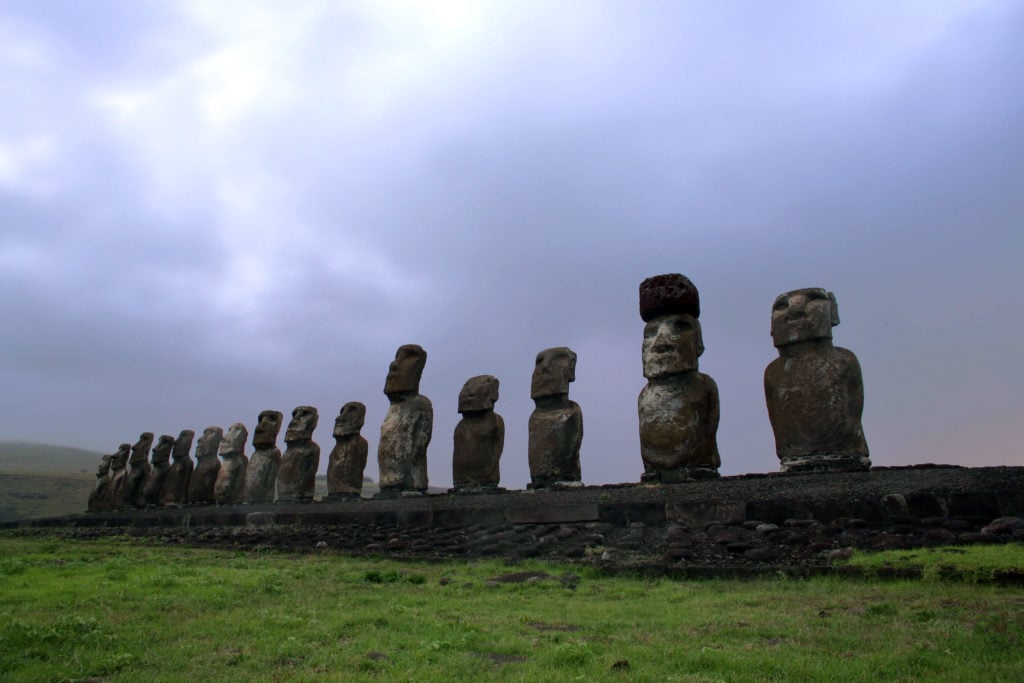

View of Moais—stone statues of the Rapa Nui culture—on the Ahu Tongariki site on Easter Island, 3700 km off the Chilean coast in the Pacific Ocean. Photo by Gregory Boissy/AFP/Getty Images.

As with the giant slabs that make up Stonehenge, researchers have long wondered how the Rapa Nui managed to move the moai into their current positions. Some 300 unfinished statues remain in close proximity to Rano Raraku, suggesting that transport was every bit as challenging as one would think.

For a while, researchers thought that the Rapa Nui moved the moai on sleds, until real-life experiments with replicas showed that this would have required some 1,500 people to pull off. Currently, the scholarly consensus is that they “walked.” Not by themselves, but by two sets of rope fastened to either side of the statues that, when pulled in the right order, leveraged their immense weight, reducing the number of people required to move them to just 40.

Photo courtesy of the Easter Island Statue Project.

Some moai are adorned with 8.2 feet tall, cylinder-shaped hats called pukao. Unlike the statues themselves, these aren’t made from volcanic tuff, but red scoria, a material formed in the volcano, but ejected in eruptions that took place long before the Rapa Nui first set foot on Easter Island. An article published in the Journal of Archaeological Science posits that the islanders placed them atop the moai using ramps, tilting the statues forward before pushing them back up.

As to what the moai are meant to signify, the prevailing theory is that they represent the Rapa Nui’s ancestral chiefs—leaders who, in their cosmological view of the world, descended from gods and protect the islanders from disasters. The hypothesis is supported by the fact that pretty much all of them face inland, to the residencies of their original builders.

Sometimes, archaeology gets big. In Huge! we delve deep into the world’s largest, towering, most epic monuments. Who built them? How did they get there? Why so big?