Moe Satt.

Image: Courtesy of the artist; photo by Allen Cui.

Sitting at an outdoor table in Yangon’s Chinatown, a plastic bag of fat, fried grasshoppers in front of him, Moe Satt makes a kissing sound three times in quick succession, summoning a waiter to order another round of beers. With friends he’ll sometimes do something different, snapping the middle finger of his left hand between the thumb and middle finger of his right, creating a resounding crack, the sonic equivalent of a secret handshake. These aren’t his only methods of getting attention. He’s also one of the leading contemporary artists in Myanmar, formerly known as Burma.

Satt is also one of six young artists nominated for the Hugo Boss Asia Art Award, which this year will be awarded to an artist under 35 from China or Southeast Asia.

The winner will be announced during a ceremony at the Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai on November 26. This is the second edition of the prize, which Hong Kong artist Kwan Sheung won in 2013 for his politically-inspired installations and videos, including a crowd control barrier filled with water and maotai, the pricey alcohol associated with corruption in China.

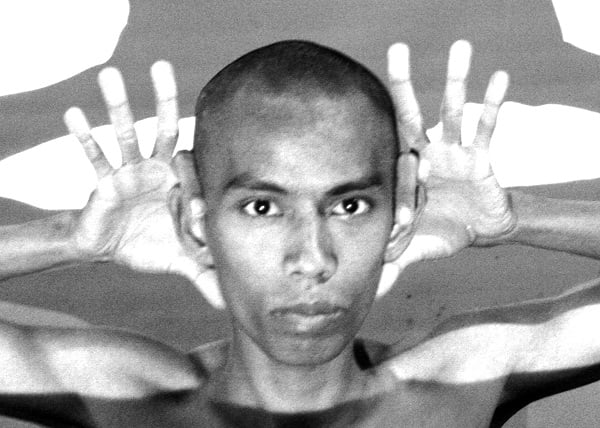

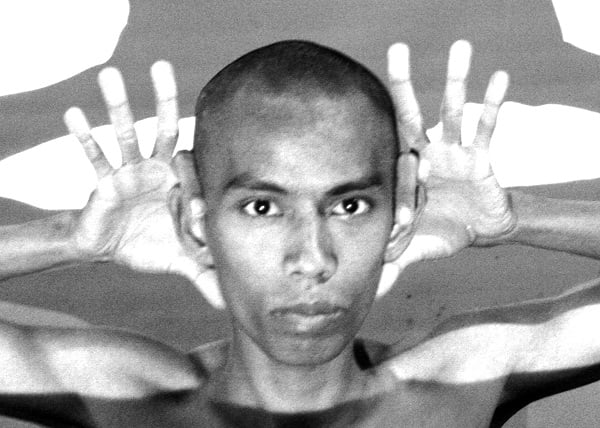

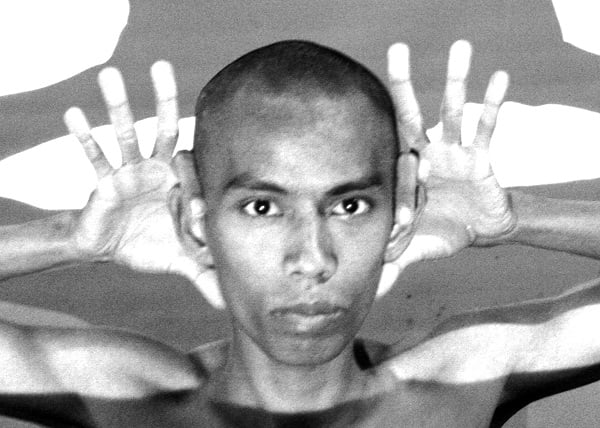

From Satt’s Face and Fingers series (2008-9).

Image: Courtesy of the artist.

Many of Satt’s works, showing at the museum until January 3, 2016, derive from the culture of the country’s Buddhist majority, which constitutes around 90 percent of the population. Face and Fingers (2008-09) is a series of photographs capturing meaningful gestures—like Buddhist mudras—of his own invention with names such as Teasing, Blossoms, Wave, and Gun, the last of which nods to the violence and intimidation of the military rulers who have controlled the country since 1962.

Satt took photos of himself performing ten new gestures a day for months, refining them down to a total language of 108, a number representative of infinity in Buddhism.

Still from Hands Around Yangon (2012).

Image: Courtesy of the artist.

A more recent work, Hands Around Yangon (2012) is a video of close-ups of people’s hands at work scraping coconuts, binding books, worrying beads, grinding cane sugar, counting money and countless other quotidian actions. Again the underlying inspiration is Buddhism, but what is observed is its more colloquial counterpart—gestures that are handy, not holy.

Satt’s father is Muslim and his mother is Buddhist; there’s a small Buddhist shrine on the wall of his home, but he himself is not religious. He jokingly complains to his wife about not being able to eat the offerings she prepares for Buddha. Why does she feed her god before feeding her husband? In a country where monks wield considerable power, and the skyline is dominated by the Shwedagon Pagoda, a 99-meter-tall pyramid of gold topped with thousands of diamonds and rubies, Satt’s secular approach feels revolutionary.

Born in 1983, Satt began his artistic career in 2005 as a performance artist, a powerful medium chosen for pragmatic reasons. With little institutional or commercial support, in addition to buying their own materials, Satt says artists here have to rent out gallery space themselves to display physical works. In one of the most impoverished nations in the region, public performances are simply cheaper.

Consequently, Satt’s apartment, a two-room sixth floor walk-up that he rents from his sister, contains no obvious art materials, though his bookshelf holds a selection of art books and catalogues in English and various other languages. Instead there’s a futon on the floor and diapers and stuffed toys for his 14-month old son, whose name means “alphabet”. Born Si Thu Tan Naing, Satt’s own name is a pseudonym (many artists take them in Myanmar) meaning “rain drop”. He chose it because he was born in July, which is rainy season in tropical Myanmar.

The winner of the HBAAP will receive an award of 300,000 RMB ($50,000) to develop their practice. Some artists nominated for the award are already making that kind of money from their exhibitions. For Satt, the prize would mean a measure of personal financial security. If he wins, he says he’ll spend it on achieving middle-class pursuits: $30,000 on an apartment, $10,000 on a car and $10,000 on daily life.

Satt has already debated his chances with some of the other nominees: Huang Po-Chih (Taiwan), Vandy Rattana (Cambodia), Yang Xinguang (China), Maria Taniguchi (Philippines) and Guan Xiao (China). Will the judges prefer to award the prize to a female artist this time? Will it go to someone more established? Will Myanmar’s historic national elections, held on November 8 and won by Nobel Prize Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD), play into Satt’s hands?

Installation view of Five Questions to the Society where I Live (2015).

Image: Courtesy of the artist.

With the election in mind, thought to be the freest in over 50 years, Satt extended his artist’s sign language through the work Five Questions to the Society where I Live (2015), also on display at the Rockbund. A neon on aluminum sign with fiberglass casts of hand gestures asks the questions “R U [okay]?”, “R U [good]?” and “R U [pro-peace]?” Satt also uses the mockingjay sign from The Hunger Games to ask the question “R U [against the junta?].”

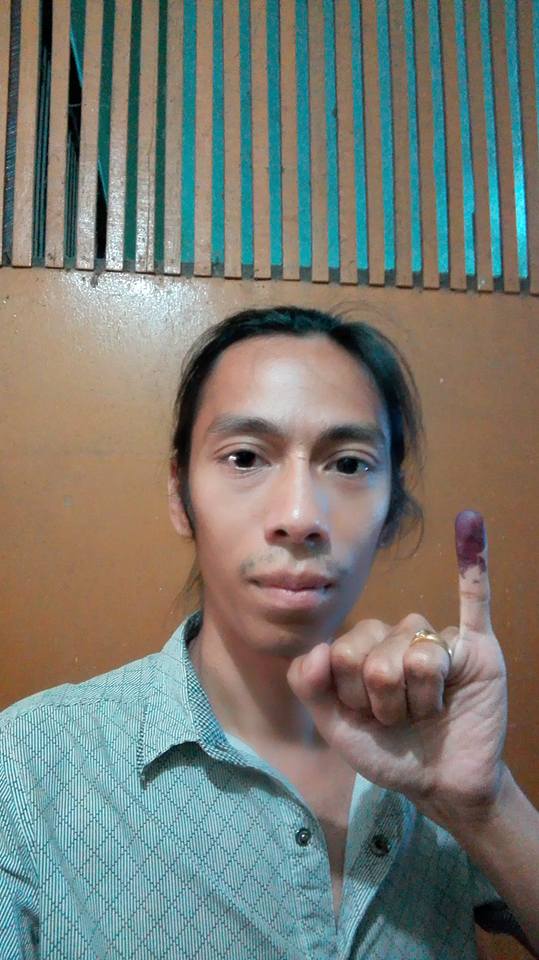

The fifth question, “R U [voting]”, is represented by a raised little finger. Satt posted a picture of himself with a red little finger on his Facebook page after voting in the general elections, showing the colored dye that prevents people from illegally voting multiple times. He says it took two days to wash off.

Political sensitivities in Satt’s work also make performance art, which is ephemeral and often camouflaged in symbolism, a prudent choice for the artist, though it’s certainly not without risk. Activist and performance artist Htein Lin, one of Satt’s obvious forebears, spent almost seven years behind bars under the junta from 1998-2004, secretly painting works on prison uniforms and carving them out of bars of soap.

Installation view of Like Umbrella, Like King (2015).

Image: Courtesy of the artist.

The largest component of Satt’s exhibition at Rockbund is an installation of 15 traditional Burmese wood and silk umbrellas, each 2.5 meters in diameter. In previous performances Satt carried such an umbrella torn to shreds.

For the work Like Umbrella, Like King (2015), the umbrellas have been cut but repaired with zippers, suggesting a cautious optimism; zippers suggest both a country being restored and the potential for progress to be undone again.

Moe Satt at a polling station.

Image: Courtesy of the artist.

Results were released slowly over the week following the election, when I visited, with the NLD finally confirming they had the numbers to form a government on Saturday, November 14. Rumors of a celebration outside the NLD headquarters that night came to nothing—everyone is waiting to see what happens next.

Winning the Hugo Boss Asia Art award would be a huge boost to Satt’s career, though it pales in comparison to the opportunities presented by a truly free country.