Museums & Institutions

MoMA Survived Ten Weeks of Protest. But Inside the Museum, Some Employees Are Feeling the Strain

A protest movement questioning the MoMA board's ties to “toxic philanthropy” came in the midst of a staffing crisis.

A protest movement questioning the MoMA board's ties to “toxic philanthropy” came in the midst of a staffing crisis.

Zachary Small

They stood outside, chanting a desire to “burn this fucking empire down.” They blocked the museum’s main entrance, leaving confused tourists to amble through some alternate corridor of the institution. They hosted teach-ins that covered everything from American racism to the plight of Palestinians in Gaza. They unloaded boxes of plantains and spilled a container of red-dyed water because they believed trustees were “washing their hands with the blood of our people.”

But after ten weeks of protest, the dozens of activists who sought to dismantle the hierarchies controlling the Museum of Modern Art found themselves pushing against an immovable force. One month after the campaign’s end, the museum appeared outwardly unaffected by the demonstrations. Behind the scenes, however, the combination of the external pressure and shrinking staff has left signs of strain at one of the country’s most prominent institutions, according to several employees.

***

The Strike MoMA Campaign, which ended on June 11 with a final march through Midtown, involved a number of activist organizations that called themselves the International Imagination of Anti-National Anti-Imperialist Feelings. The coalition formed in response to news that the billionaire Leon Black would leave his position as the museum’s chairman after widespread pressure from artists and activists over his ties to the convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. (Black remains on the board.)

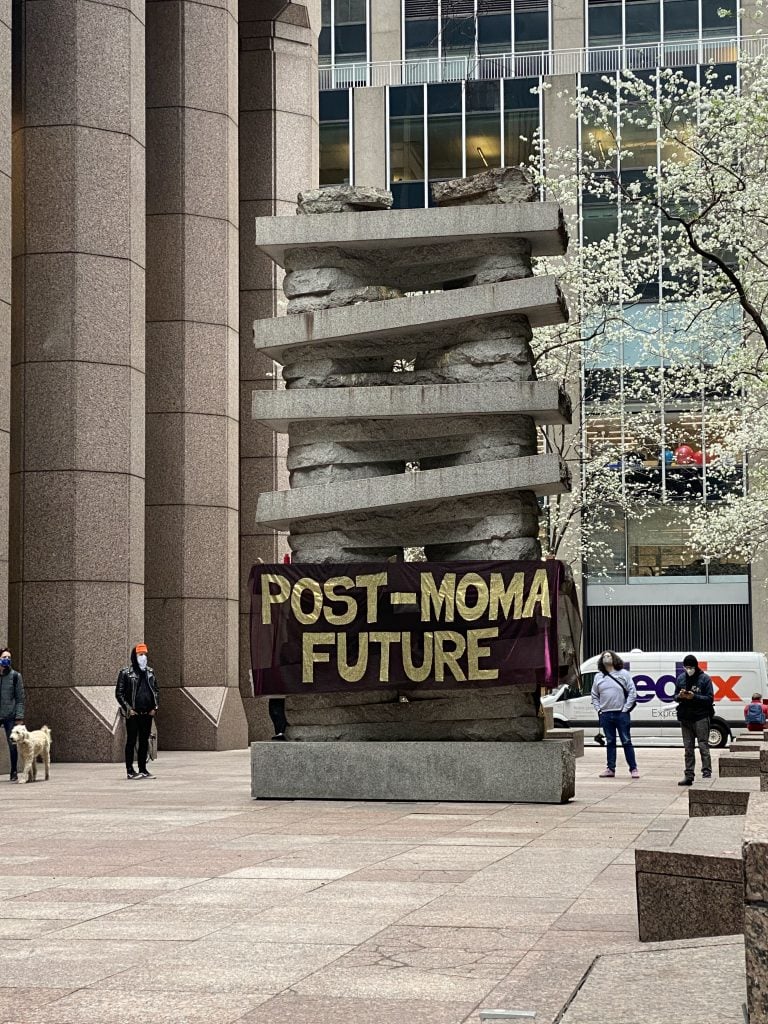

Activists rally at the Museum of Modern Art. (Photo by Lev Radin/Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty Images)

Demonstrations were primarily led by members of Decolonize This Place, an organization that had led a nine-week protest campaign at the Whitney Museum which ended with the resignation of the vice chairman, Warren B. Kanders, who activists said was not fit to serve as a trustee because his company, Safariland, sold law enforcement and military supplies, including tear gas.

No such concessions were given at MoMA, where Glenn Lowry, the museum’s director, described the protesters as forces intending to “destroy” the beloved institution in an April email to staff.

“Do we have a lot more work to do? For sure,” he wrote at the time. “Can we be an even better institution? For sure. Is the protesters’ call to destroy MoMA the solution? I don’t see that helping anyone.”

The conflict reached its boiling point on April 30, when the museum said it was forced to shut its doors after protesters attempted to force their way inside without abiding by health and safety rules. “The protesters chose not to act safely or peacefully,” a MoMA spokesperson told Artnet News after the confrontation. “The museum will always act to protect the health and safety of our staff and visitors.”

According to the spokesperson, two guards were injured by protesters. One protester said that she was punched by a guard when trying to access the museum through an alternate entrance.

Police and Strike MoMA protesters. Photo: Zachary Small

The museum later announced that five activists would be permanently banned from the institution. Dozens of police officers and several unmarked police cars started appearing at the protests. During another demonstration in May, which centered on the plight of Palestinians, a protester was tackled by police and arrested near the museum.

Some employees would come to the museum windows and look across 53rd Street on Friday afternoons, watching as activists congregated in the nearby plaza to raise their “Strike MoMA” flag. And when the protesters were initially locked out of the museum in April, at least two staffers walked out of the museum in frustration.

It was a rare show of dissent within an institution that has largely avoided controversy or rank-breaking in a year when staff at large museums like the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Guggenheim have publicly confronted leadership on subjects like equity and diversity.

***

Although the protests have ended, the mood inside MoMA remains tense, according to several staff members. The pressure from external forces coincided with an unprecedented moment of strain within the institution. Last summer, Lowry said in a video conference that his institution had reduced staff by nearly 160 employees and slashed $45 million from its overall budget.

MoMA has also experienced significant departures through the COVID-19 pandemic beyond what has been previously reported on its termination of contracts with 85 freelance educators. There have been buyouts and early retirement packages offered, and all three senior deputy directors have left the museum, with Ramona Bannayan, senior deputy director of exhibitions and collections, leaving in May.

A Strike MoMA action outside the museum. Photo: Zachary Small

A MoMA spokesperson did not respond to several requests for comment for this story, although a source close to the museum board said that a communications executive had informed trustees of this article before its publication.

Low morale and widespread feelings of burnout in what has become a middle-heavy organization have left some employees questioning the decisions of MoMA leadership, according to five staff members, all of whom spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation.

Several employees said that the museum’s communications strategies inside and outside of its walls had become a source of division. “There isn’t space to talk about anything,” one said. “Our staff meetings involve questions that are all vetted beforehand.”

Another staff member estimated that nearly half the museum supported the protesters’ goals while the other half objected to them. But the fact that the museum had initially told staffers in a meeting that demonstrators would be allowed inside the building, only to lock the doors, stoked feelings of distrust among the employees who spoke with Artnet News.

“From the outset, there was a lot of anxiety from senior leadership and trustees that a majority of staffers might stage a walkout in solidarity with Strike MoMA,” said one employee. “So the museum decided to hide behind its security officers… putting staff, who are predominantly people of color, in harm’s way” when protesters arrived at the front doors.

So many security guards had accepted early retirement packages that the department was excluded from a later buyout program, staffers said. Some employees speculated that the museum’s decision to reduce its security detail during the pandemic resulted in a situation where personnel were overextended and understaffed for the protests.

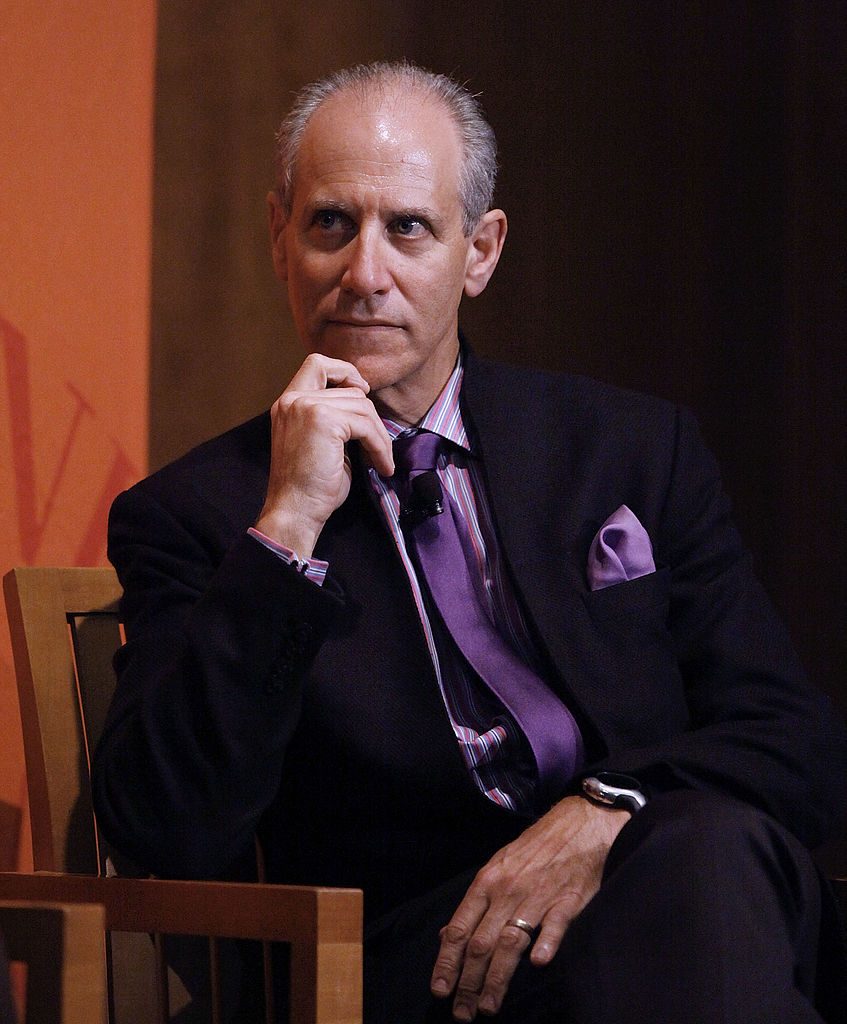

Glenn Lowry, director of MoMA. (Photo by John Lamparski/WireImage)

“It’s bad enough that we don’t have any shows lined up for the special exhibition space, it’s that we don’t even have the manpower to put them up,” said another employee. “Art handlers aren’t allowed overtime anymore and people in temporary positions have been termed out. The museum isn’t currently trying to fill those positions.”

***

During the final protest in June, many demonstrators interviewed by Artnet News said that Strike MoMA symbolized a beginning—not the end—of a larger movement aiming to hold cultural institutions accountable. Their actions, some hoped, would also expose the inequalities within the museum system—but they also served to illustrate just how large a gap remains between their goals and methods and those of traditional museum leaders.

“The abolition of slavery should be followed by the abolition of the museum, where plunder continues to be cultivated as private property,” said Ariella Azoulay, a professor at Brown University who spoke to activists during an online component of the protests.

“A practice of repair,” Azoulay said, echoing what some employees inside the museum told Artnet News, “should take over the infrastructure of the Museum of Modern Art and become its guiding principle.”