On View

MoMA’s ‘New Photography’ Show Spotlights Young Photographers Making the Medium Tactile. There’s Just One Problem: It’s Online Only

“Companion Pieces: New Photography 2020” is on view through MoMA’s Online Magazine now through March 21, 2021.

“Companion Pieces: New Photography 2020” is on view through MoMA’s Online Magazine now through March 21, 2021.

Taylor Dafoe

Of all the exhibitions that have moved online during the lockdown era, one would imagine that the Museum of Modern Art’s latest edition of “New Photography,” a series that spotlights emergent trends and talents in the genre, would be among the easiest to convert to computer screen. It’s ironic, then, that the show is, in fact, about the physicality of photographs.

In the work of the eight participating artists, photos are torn and painted and stitched together; they’re fitted into antique frames the size of a matchbox and printed on canvases that run longer than a station wagon. Clicking through a series of windows online, you can’t help but feel something was lost in translation.

This wasn’t the intention. “Companion Pieces,” as the show is called, was conceived prior to the pandemic. But the tension between virtual viewing and tangible imagery does serve a purpose. It reminds us that photographs are not autonomous; the context in which an image is presented is as significant as the image itself. And that, says curator Lucy Gallun, is what the show is really about.

Irina Rozovsky, Untitled from “Miracle Center” (2019). Courtesy the artist © Irina Rozovsky.

Over the course of two months beginning in late September, the work of each “Companion Pieces” artist debuted once a week on MoMA’s online platform Magazine—a format more akin to editorial features than museum presentations. (The full show is online now.) It marks the 26th iteration of New Photography, and the first to live on the web.

For its initial three decades, the John Szarkowski-founded series arrived annually as a loose showcase of roughly three to seven artists’ work. By 2015, when it was rebranded to a biannual, more thematically-driven format, the series had long cultivated a reputation as a kind of weather vane known for showing which way the winds of the medium were blowing. (Among the names of those who have been featured are Philip-Lorca diCorcia, An-My Lê, Wolfgang Tillmans, and Deana Lawson.)

Recently, the museum was looking to do more with the series, Gallun tells Artnet News. “For the last few years, we’ve wanted to really be able to talk about urgent issues in photography and not just be this platform for artists that exists without saying anything about what their works might mean in conversation with one another,” the curator explains.

David Alekhuogie, Target (2019). Courtesy of the artist and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles. © David Alekhuogie.

The latest iteration, “Companion Pieces,” seeks to embody this new approach. “Rather than thinking of them as discrete images or art objects,” Gallun says,” I was thinking about how images don’t live in isolation and how artists have recognized that. I felt like I was seeing many artists take up this idea of one image being dependent on another, or looking back to an older picture to say something new about today.”

For those looking for an entry point into the show’s slippery themes, the curator volunteers a helpful art-historical metaphor: a pendant, or a pair of paintings that together tell a story, often over an implied period of time. The name derives from the Latin word for hanging and implies a codependency between objects—and you’ll find manifold examples of both in the work on view.

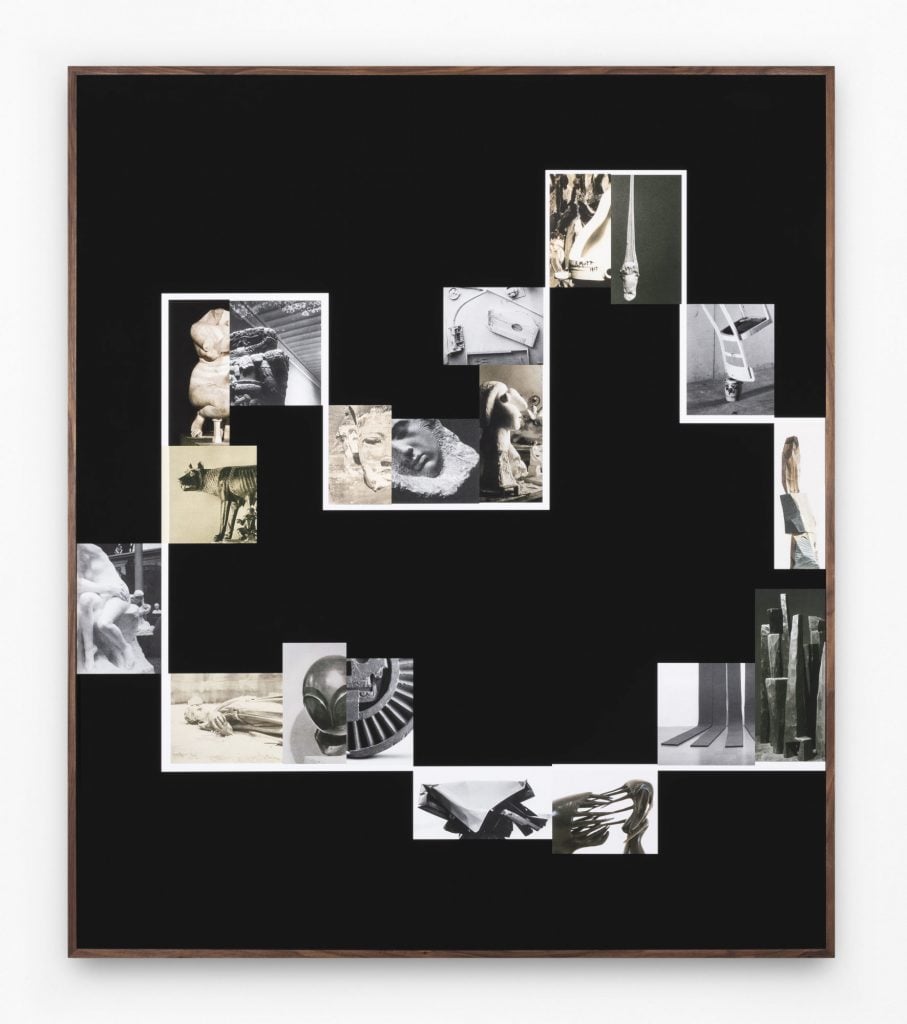

Mexican artist Iñaki Bonillas, for example, collages photo scraps culled from books in his library. The images are adjoined by a common border—blank blocks from the margins of the source books—a tactic that recalls both Mondrian and the 8-bit computer game Snake.

Iñaki Bonillas, Marginalia 7 (2019). Courtesy of the artist and kurimanzutto, Mexico City and New York. © Iñaki Bonillas.

In a pair of complementary series by Indian artist Sohrab Hura, meanwhile, the invocation of the pendant is more thematic. Each body of work, “Snow” and “The Song of Sparrows in a Hundred Days of Summer,” takes place during a different season in a different location in Hura’s home country. Taken together, another narrative layer comes to the fore.

“What I realized over time,” explains the artist in an audio interview accompanying his work, “was that I was looking at two extreme landscapes—one being a socioeconomic landscape in Central India, whereas Kashmir became this political landscape.”

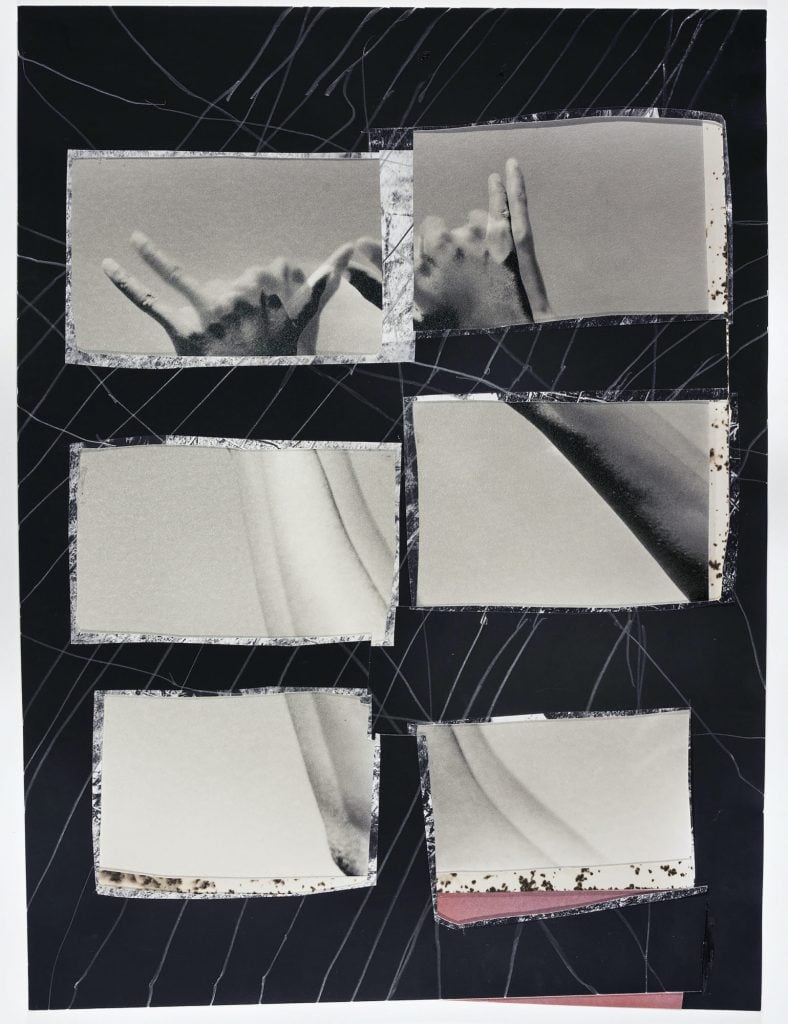

The landscape, and the ways in which photographs mediate our relationship to it, is also a central concern of American artist Dionne Lee. Lee’s darkroom photomontages don’t look like the landscape photographs of, say, Ansel Adams. But that’s the point: her work prods at the ways in which images of nature have been used to craft the narrative of history—and, in some cases, write groups of people out of it.

Informed by a similar gesture, American artist David Alekhuogie taped close-up pictures of Black bodies throughout outdoor spaces in Los Angeles and rephotographed them. “There’s a call-and-response,” says Alekhuogie in an interview, “between my landscapes and Los Angeles.”

Dionne Lee, True North (2019). Courtesy of the artist. © Dionne Lee.

That’s one benefit of the show’s hybridized form: we’re offered more of the artists themselves than we’d get on the wall of a museum. To hear the artists describe their work in their own words offers a welcome dose of personality that helps make up for the intimacy lost in seeing their handcrafted creations online.

“I think the form came out of our goals for the show,” Gallun says. “There’s an opportunity, I think, to spend more time with each artist and we put forward their practices and their approaches individually.”

For an exhibition drawn up before the days of quarantine, the final product captures one signature theme of the era: adaptation.

“Companion Pieces: New Photography 2020” is on view online now through March 21, 2020.