On View

‘Harmony Is Never Symmetry’: The Curator of Fondation Beyeler’s Deeply Researched Mondrian Show on What Made the Artist Tick

"Mondrian Evolution" is the product of a multi-year effort.

"Mondrian Evolution" is the product of a multi-year effort.

Taylor Dafoe

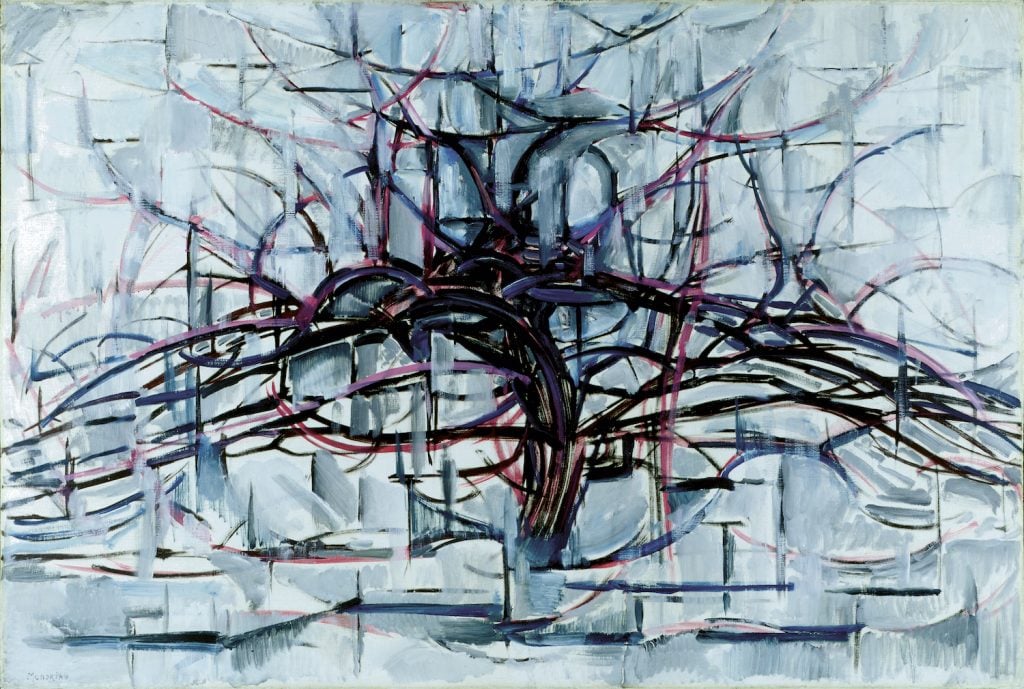

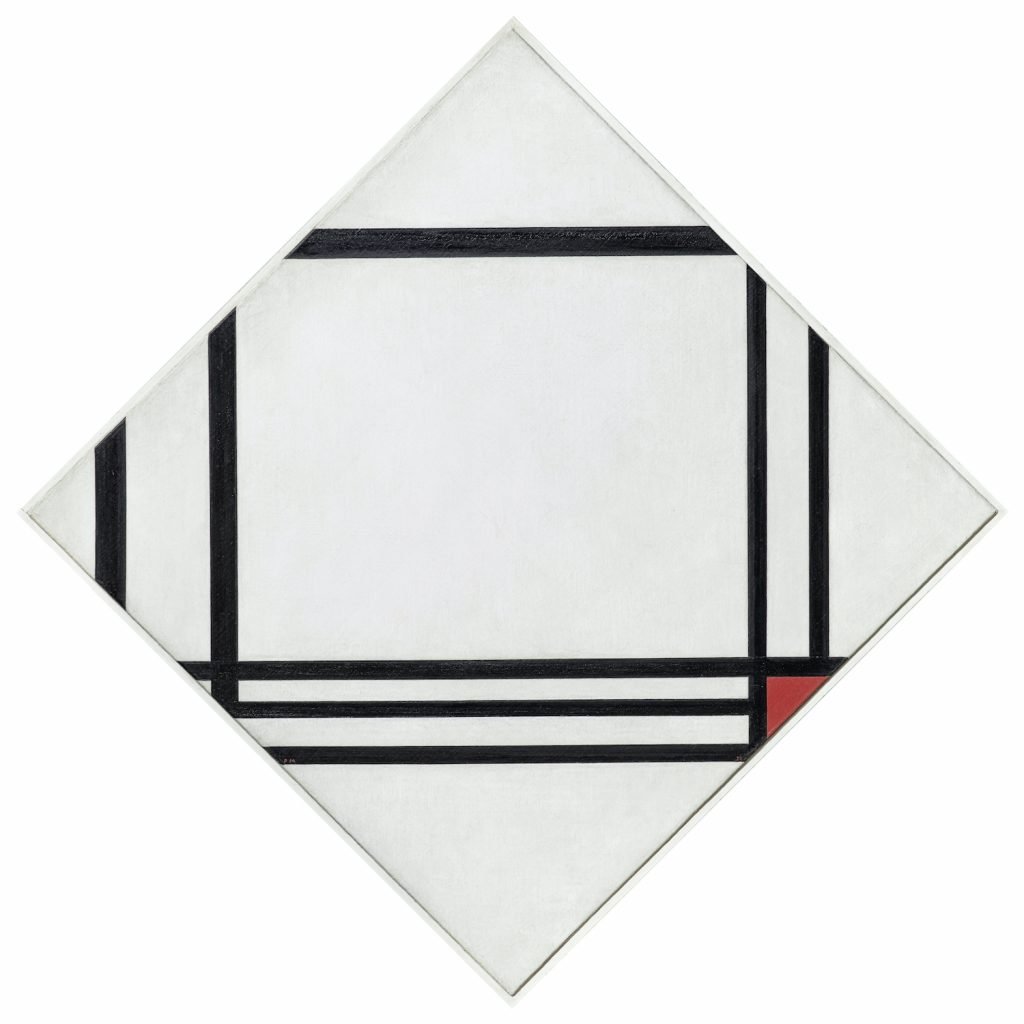

Piet Mondrian—the Dutch painter synonymous with rigidly gridded abstractions—never used a ruler, it turns out.

That was one of numerous revelations highlighted by conservators at the Fondation Beyeler in Basel, Switzerland, who have concluded a multi-year research project that preceded a retrospective of the famed artist, which is on view now through October.

Mondrian “made marks at the edges, then very slowly painted these lines. They look precise but they are based on intuition,” said Ulf Kuster, who organized the exhibition. For the Dutch artist, painting was a “long process of looking, of composing, of erasing,” the curator explained.

The Neo-plasticist’s greatest hits abound with myriad right angles and intersecting lines, so it’s hard to believe that he didn’t use an aid. But Mondrian’s hesitance to using a ruler says more about his dogmatic—and often arduous—approach to art, Kuster pointed out.

Piet Mondrian, Composition With Yellow and Blue (1932). © Mondrian/Holtzman Trust

Photo: Robert Bayer, Basel.

“I really learned that [Mondrian] was a painter who was always in control of what he did,” the curator said of his experience working on the show. “I didn’t realize how painstaking this process of painting must’ve been for him and how thoughtful he looked at things and how much he reflected on painting.”

“Mondrian Evolution” is the name of Kuster’s exhibition, which marks the 150th anniversary of the artist’s birth. It also doubles as a description of what viewers can expect at the Beyeler: a tip-to-toe survey of Mondrian’s career, beginning with his younger efforts in portraiture and landscape.

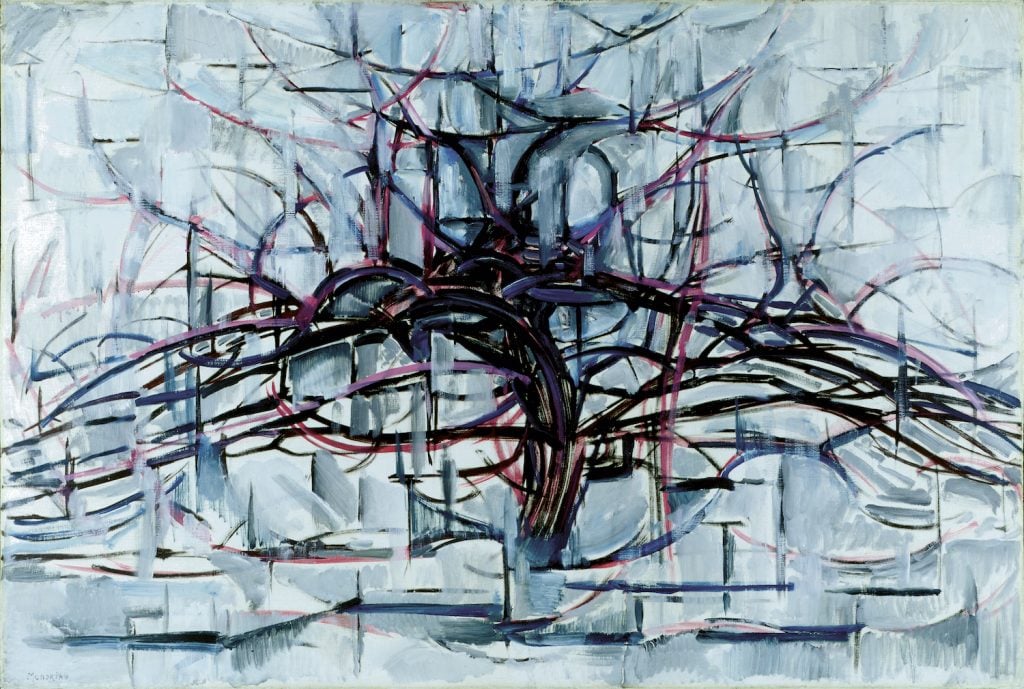

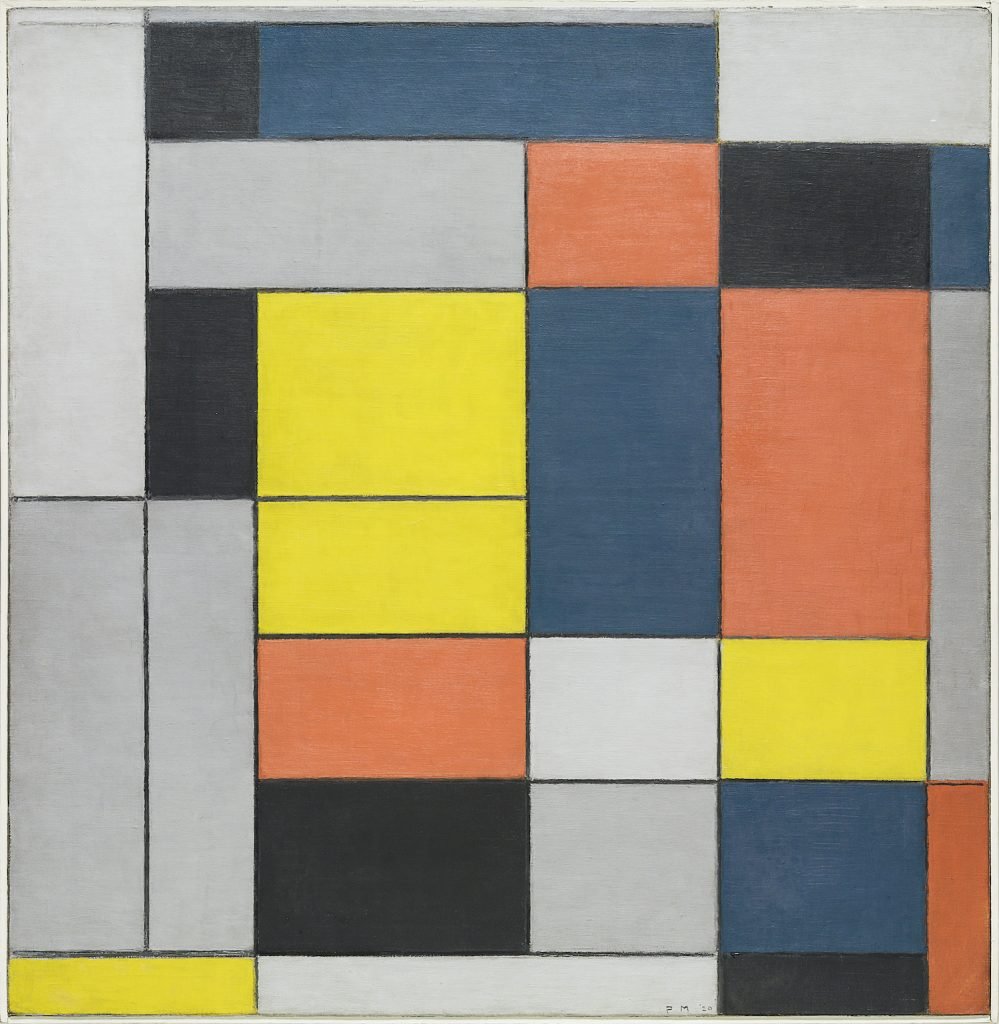

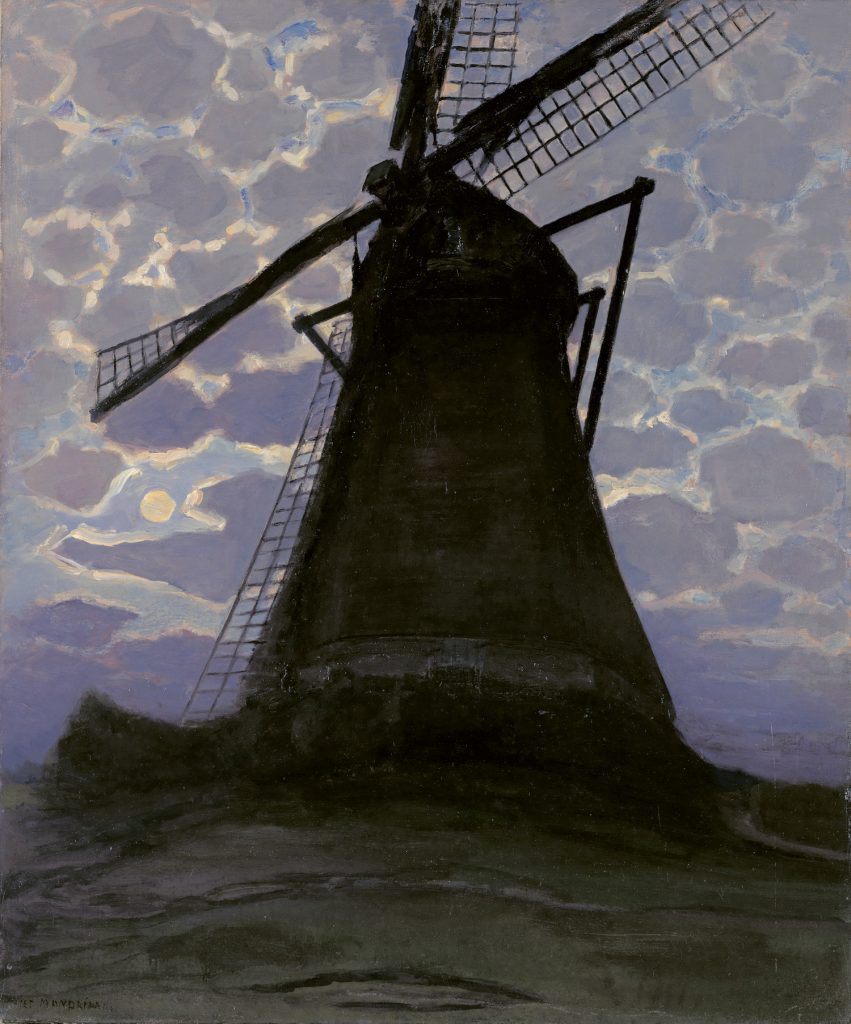

Those early paintings, completed in the Netherlands just before and after the turn of the 19th century, don’t look like the ones for which he would later become known. But it’s also not hard to spot shared strands of DNA. See, for instance, his many studies of whirling windmills and multi-branched trees: it’s clear that, even then, the artist was trying to translate into oil paint the geometry that governs the world around us.

“He was looking for harmony, but harmony is never symmetry,” Kuster said. “Harmony has to have tension over time.”

Piet Mondrian, Mill in Sunlight (1908). © 2022 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust. Photo: Kunstmuseum Den Haag.

With exposure to painters like Picasso and Braque, and a multi-year stint in Paris, abstraction began to suffuse Mondrian’s canvases around 1911. His once-representational scenes of Dutch waterways dissolved into Cubist abstractions that, while still based in the lived world, prioritized form over content.

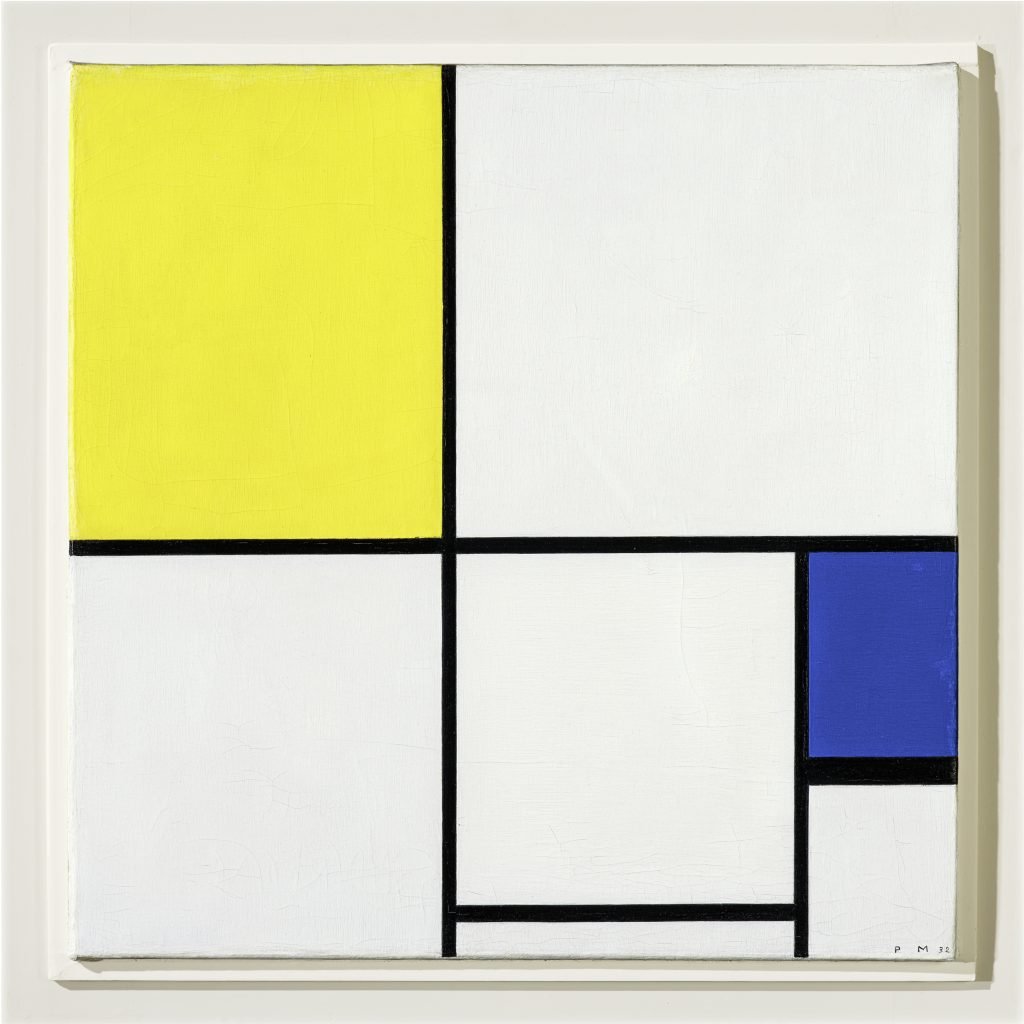

Within the next decade, he returned to the Netherlands, then went back to Paris. His loosely-painted cubes morphed into hard rectangles; his cool, fauvist-inspired palette was replaced by solid bands of color. The style that would come to be known as “De Stijl” was born.

From classic figuration to cutting-edge abstraction, the full trajectory of Mondrian’s work on view at the Beyeler mirrors the evolution of modernism itself. However, the Dutch artist also shows us the importance of looking beyond that familiar story, Kuster pointed out.

“Mondrian is someone who teaches you a lot about painting,” said the curator, demonstrating his own affection for the artist. “The very art historical—and in many ways helpful—idea that modern art is a development from figuration to abstraction is okay, but it’s not really interesting to artists.”

“For an artist,” Kuster went on, “It’s not important if it’s representational or non-representational, because it’s always abstract. It’s always abstract, because painting is abstraction.”

See some of the highlights of “Mondrian Evolution” below:

Piet Mondrian, No. VI / Composition No.II (1920). © 2021 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust

Photo: Tate.

Piet Mondrian, The Red Cloud (1907). © 2022 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust. Photo: Kunstmuseum Den Haag.

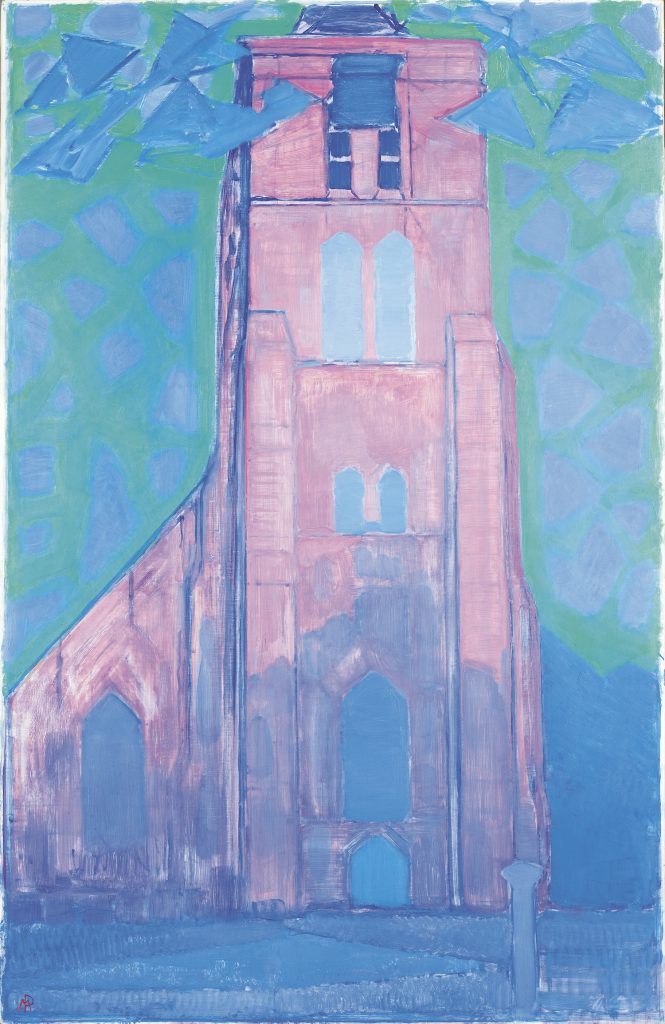

Piet Mondrian, Church Tower at Domburg (1911). © 2022 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust

Photo: Kunstmuseum Den Haag.

Piet Mondrian, Windmill in the Evening (1917). © 2022 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust. Photo: Kunstmuseum Den Haag.

Piet Mondrian, Woods Near Oele (1908). © 2022 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust. Photo: Kunstmuseum Den Haag.

Piet Mondrian, Flowering Apple Tree (1912).

© 2022 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust

Photo: Kunstmuseum Den Haag.

Piet Mondrian, Lozenge Composition with Eight Lines and Red/Picture No. III (1938). © Mondrian/Holtzman Trust

Photo: Robert Bayer, Basel.

“Mondrian Evolution” is on view now through October 9, 2022 at the Fondation Beyeler in Basel, Switzerland.