Art & Exhibitions

On the Money: A New Show Explores How Artists Have Left Their Mark on Cash

"Money Talks" explores how artists from Beuys to Banksy have dealt with currency.

If you’ve ever looked at a coin or a banknote and thought, “Now, that’s an artwork I’d like to have in my home,” the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archeology in Oxford, England, has an exhibition for you.

“Money Talks: Art, Society & Power,” which explores the place of money in our world through various artistic lenses, features over 100 pieces of currency and currency-inspired artworks, from Roman, Islamic, and Chinese coins to original works by artists including Rembrandt, Andy Warhol, and Banksy, as well as a selection of NFTs.

One of the lessons this exhibition teaches is that money can and should be recognized as art. In order to prevent counterfeiting, banks and governments throughout history have routinely turned to artists and craftspeople to adorn their currencies with complex, inimitable designs, images, and motifs. This practical measure had the added effect of imbuing coins and notes with artistic value, from Roman denarii with busts of emperors to golden dinars from 9th-century Moorish Spain, decorated with hand-carved lines of Arabic scripture.

Gold Aureus of Nero. Photo courtesy of Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

Modern currencies were at times designed by better-known artists, like Koloman Moser’s draft artwork for 50 crown notes, commissioned by the Austro-Hungarian Bank in 1902. A professor of decorative drawing and painting at Vienna’s Kunstgewerbeschule, Moser was a member of the Vienna Secession, an art movement that rejected traditional fine art styles in favor of experimentation and craft.

Koloman Moser, 50 crown note (1911). Courtesy Austrian National Bank.

In an effort to turn everyday objects into art—and stick it to the proponents of Austrian Hochkultur, or high culture—Moser not only made banknotes but also worked as a designer for textile and furniture firms like Johann Backhausen & Söhne, Prag-Rudniker, and Jacob & Josef Kohn.

Also included is a 10 shilling banknote issued by the Bank of Jamaica featuring a portrait of Queen Elizabeth II based on a photograph taken by Dorothy Wilding, the first woman to serve as the official royal photographer during Elizabeth’s 1937 coronation.

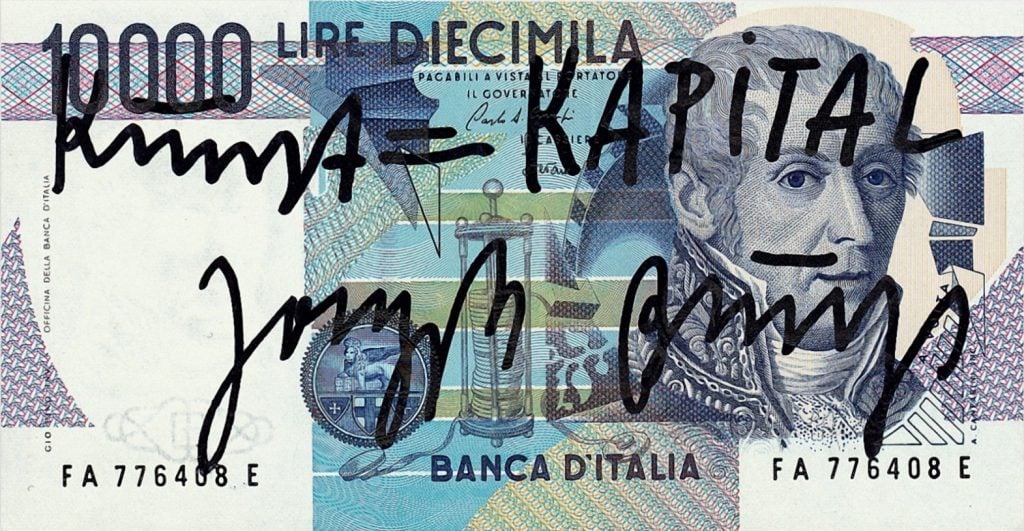

Joseph Beuys, Kunst = Kapital (10 000-Lire-Schein) (1984). Haupt Collection. Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum.

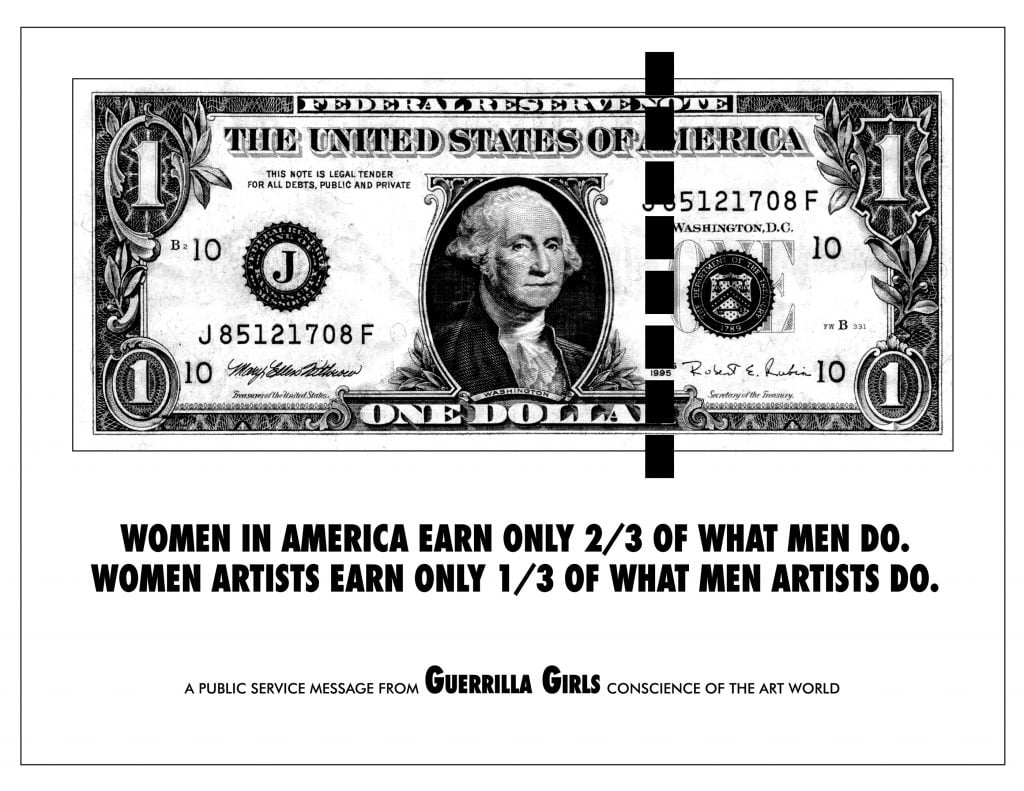

Aside from actual currency, “Money Talks” also features plenty of money-inspired art by the likes of Joseph Beuys and Guerilla Girls. In Indian artist Tallur L.N.’s 2011 sculpture Unicode, a clump of bronze, coins, and concrete assumes the place of the cosmic dancer Nataraja, a form of the Hindu god Shiva and a symbol of time and creation.

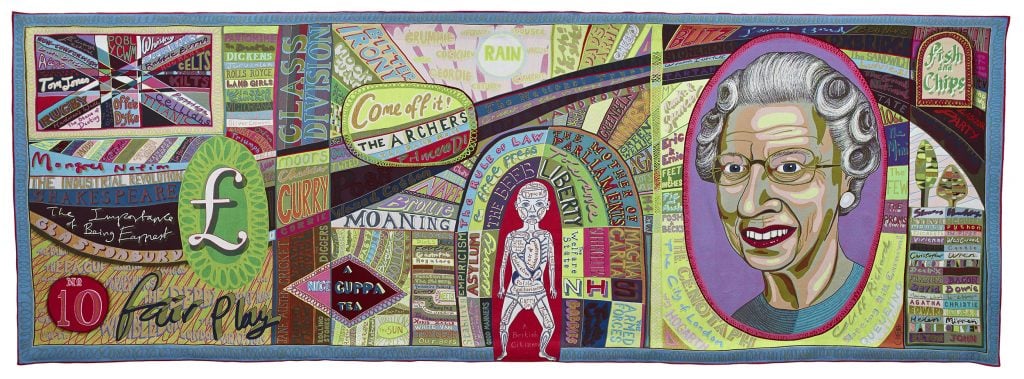

Grayson Perry, Comfort Blanket (2014). Photo: Ashmolean Museum, Oxford University.

Last but not least, there’s Comfort Blanket by English artist and writer Sir Grayson Perry, a 26-foot-wide tapestry filled with a Where’s Wally–like (or, for North Americans, Where’s Waldo–like) level of visual detail which the artist describes as follows:

A portrait of Britain to wrap your self [sic] up in, a giant banknote; things we love, and love to hate. A friend whose family had walked out of Hungary fleeing the Soviet invasion in 1956 said her mother referred to Britain as her ‘security blanket.’ As their plane came in to land in the UK, the tannoy relayed a message from the Queen saying ‘Welcome to Britain, you are now in a safe country.’ People still come to our country for its stability, safety and rule of law. We should be proud of that.

“Money Talks: Art, Society & Power” is on view at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford University, Beaumont Street, through January 5, 2025.