Artists

Artist Monica Bonvicini on William Blake, Rage, and Touching Art

The Berlin-based artist is opening her first solo exhibition with Tanya Bonakdar Gallery in New York City.

The 19th-century poet William Blake wrote an unforgettable line in “Auguries of Innocence” denouncing the infringement on freedom: A robin red-breast in a cage, puts all heaven in a rage.

Since it was first published, “it has been circulating in rock music and the mainstream,” artist Monica Bonvicini said as we stood in her bright studio on a late summer day in Berlin. That kind of tumbling connotation, through centuries and in and out of different contexts, is what interests her about Blake’s lines. As does this one word, “rage,” which becomes particularly loaded when a woman picks it up and tries to do something with it.

Alongside rage, there are others: Anger, furiousness, hysteria. All are found peppered into literary history, both in and beyond Blake’s works, and each is a term that has been felt by women—or used against them. In this context, Bonvicini has taken each of these terms on in her art practice, either as themes or formally in her text-based works. Her solo show with Tanya Bonakdar, which opens in New York during Armory Week, borrows the Blake line, but changes it from dreamy foreboding to a direct call out. “Put all heaven in a rage” is the title of her first exhibition with the dealer, who she began working with in 2022.

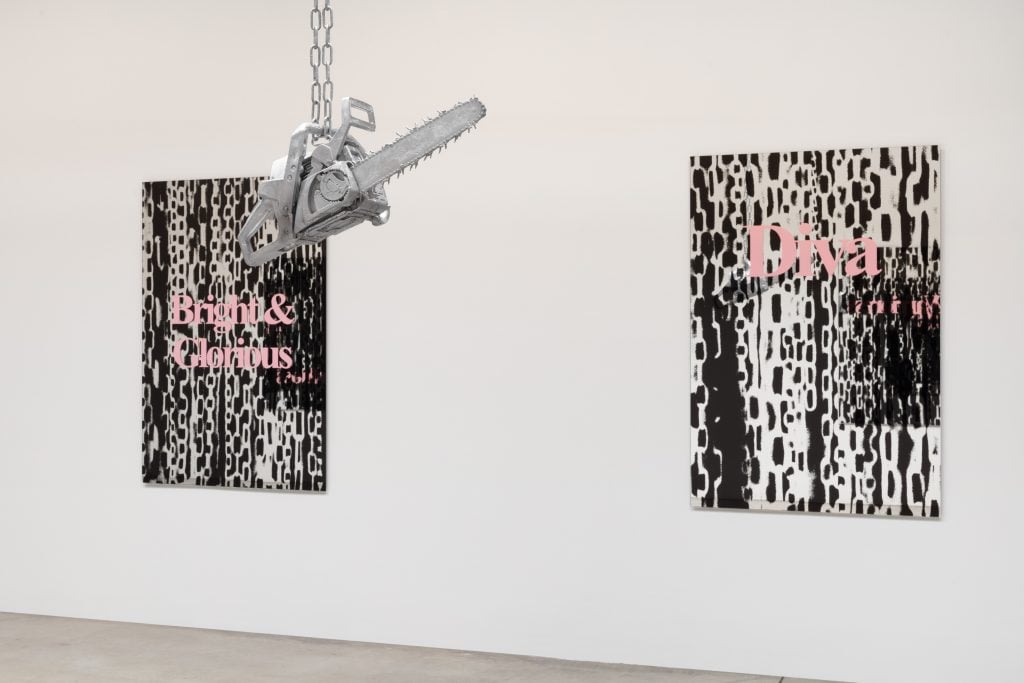

Installation view of Monica Bonvicini’s “Put All Heaven in a Rage,” Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, (September 4–October 12, 2024). Photo: Pierre Le Hors. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles.

In her large working space, with polished concrete floors and wide windows, metal housing tracks snake up and down the high ceilings. There are not enough outlets in the stone-walled space, she told me, pointing to the ceiling tracks, which she installed to help her run cables to power tools and light up fluorescent bulbs. They hang over various working work tables. The system echoes some of the sculptural forms Bonvicini is known for implementing or referencing: Work has been suspended from ceilings, be it with chains, swings, or whips. Several examples of her ongoing hanging series of bulb sculptures, including Roll Down, are on view at Tanya Bonakdar; they are made of LED tubes are woven with cables and wires into a roll-down door shape, reminiscent of the kind you see on shop storefronts around New York.

The artist uses the surfaces of steel, metal, or glass to great effect, and the materials are all the more emphasized by her precise execution of machine-made cuts that form perfect edges, so much so that the objects go from feeling industrial to fetishistic and sensual. Near us, against a large wall are a series of silkscreen paintings midway through being made. Further down the wall are a pair of new sculptures, silver chain knots that catch the light as longer chains hang and sway. At the bottom of each is a set of German-made handcuffs. Not the police kind, the play kind—but good ones, she clarified.

To say her work is about feminism and kink would be oversimplifying. “Sometimes, you get labeled with certain topics, which I do not mind because I know that that is not only what I do,” she replied when I asked about some of the classifications given to her practice.

Installation view of Monica Bonvicini’s “Put All Heaven in a Rage,” Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, (September 4–October 12, 2024). Photo: Pierre Le Hors. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles.

Work on the silk screen wall pieces has stopped because it is daytime; Bonvicini told me she prefers to work at night so she can project properly onto the wall. “I try to come to the studio early because there is a lot to discuss and organize,” she said, adding a moment later with a smile: “I am not the first to come but I am the last to go.”

On view in New York is a selection of these works. Blake’s words feature again in a silk screen painting, which overlays ancient column ruins and his remixed quote. Others feature stitched-together quips from more contemporary internet culture—including a work with printed chains that says girlboss and another with the words own your own desire. This fragmentation, and upcycling from various architectural, literary, or pop cultural references is an ongoing exercise for Bonvicini. One can see elements of different referents sprinkled throughout her work, which is spaced out in different areas of the studio that we move between.

“I get bored very fast,” she said, picking up a hand-sized glass sculpture. “I want things done quick; I think everything must be easy to do. Though, life is often not like that.”

Bonvicini came up in the 1990s Berlin and L.A. art scenes, establishing herself as a prominent voice among her generation of artists, exploring the dynamics between architecture, power, control, and gender. Born in Venice, she grew up there for some years before moving to Brescia in the north, a city nestled Lombardy region that is part of the “industrial triangle” of Italy.

“It is probably a combination of these two places,” said Bonvicini, when I asked her about how the cities influenced her practice, both of which are considerate of architecture as medium and as content. “I remember taking pictures of the industrial zones, in Brescia, where there was one hall of production after another. I’ve shown some of these photographs to Allan Sekula when I went to CalArts in the 1990s and he thought I had taken the pictures in L.A.” While studying there, she was mentored by the acclaimed conceptualist Michael Asher.

Installation view of Monica Bonvicini’s “Put All Heaven in a Rage,” Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, (September 4–October 12, 2024). Photo: Pierre Le Hors. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles.

Art history, which is everywhere in Italy, is invoked in many of her works. In a fjord in Oslo, you will find her monumental glass and steel work She Lies, a permanent fixture jutting out of the water, a machine-age interpretation of Caspar David Friedrich’s seminal painting Das Eismeer, where ice sheets jut out from the sea. In the 2011 Venice Biennale, she presented a work called 15 Steps to the Virgin, a large installation of stairs with sonic elements that referenced the painting Presentation of the Virgin, by one of Venice’s most famous artistic exports, Tintoretto, as well as much the modernist takes by Le Corbusier or even pre-Raphaelites.

Borrowing from these famous male figures from history is slightly loaded, especially when paired up with rhetorics around rage. “I personally can get angry, but I do not know how to express it generally; I am not a person who goes around yelling,” she said. “I thought rage and anger were interesting issues to talk about and discuss in art, after women being labeled as hysteric for centuries.”

According to Bonvicini, the biggest revolution of the last century was feminism: “It changed so many things.” At the Belvedere in Vienna in 2019, Bonvicini made a work of refusal, one could say. In the middle of the gallery was a large steel walled-in room, complete with spiral razor wire. Viewers could only walk around it, one one wall the word hysteria was embossed. A stencil of the Marlboro man was kiddie corner. This kind of hyperbole is playful on the one hand, and also dead serious.

Installation view of Monica Bonvicini’s “Put All Heaven in a Rage,” Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, (September 4–October 12, 2024). Photo: Pierre Le Hors. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles.

She recalled noticing an uptick in books about rage during lockdown, in new publications on feminism in particular. But, while her work metabolizes these sentiments or their related theories, it is not angry—in spite of what some have thought of it over the years. It is actually rather cheeky, and packed with many literary references.

“I met some colleagues or collectors who got frightened by my art, like they took some works on a very personal level,” she said. On a shelf, are hand-blown glass pieces that look like phalluses; one is modeled after a three-prong coat hook and, within this cosmos of her other works, it looks a bit like a sexual organ. “My works are never really and only ‘against.’ There is also lots of humor in them, even when they are direct and confrontational. Some works are very critical of certain behaviors categorized as male but it has never been as if I want to cut dicks or something like that. It has never been so simple.”

My favorite of the new works is a series of highly reflective glass works—paintings, you could call them—in delicate fleshy hues. There is a hole cut into them and a hand-blown glass tongue hangs out. It is a provocation; your own reflection seems to be making fun of you. Seeing this immaculate surface with one very clear artistic intervention, I also could not help but think of Lucio Fontana’s gashed paintings.

Monica Bonvicini, Upper Floor, (2022). Installation view Neue Nationalgalerie. Courtesy the artist, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Galerie Krinzinger. Copyright the artist, VG-Bild Kunst, Bonn, 2022, / Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / Jens Ziehe.

That use of reflection plays with the choreography of viewers trying to find their way through exhibition spaces at larger scale: like at the Belvedere, at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin in 2022, Bonvicini installed a massive mirror-like structure into the middle of the space, “appealing you and rejecting you,” as she put it. Around the opulent yet modern Mies van der Rohe building were swings and dangling handcuffs; the latter work, called You to Me, that you could attach yourself to (but only if you followed certain rules: you had to stay for 30 minutes and you could not use your phone at all). “I have been interested since the beginning in how an installation or sculpture can have a performative life,” she says when I ask her about the motivations for this work.

“It takes some guts,” she said of the viewers who would opt in to be handcuffed. “You to Me offered a serious experience that could have and did have funny moments as well.”

Installation view of Monica Bonvicini’s “Put All Heaven in a Rage,” Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, (September 4–October 12, 2024). Photo: Pierre Le Hors. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles.

That subtle playfulness is perhaps most evident with her swings. The classic piece, Never Again (2005)—an incredible work of galvanized steel pipes, black leather men’s belts, chains, and clamps fashioned into swings—was a talking point at Art Basel Unlimited last year. That work had initially been presented at Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin’s now preeminent contemporary art museum, but back when it was in its sleepier era.

“I planned [it] specifically for Hamburger Bahnhof, Nationalgalerie der Gegenwart, knowing very well the museum and how boring it was,” she said. “The museum has a totally different life now.”

The artist is interested in playing with institutions as site of intimidation for the public, but also questioning what meaningful interaction is from a viewer.

“Back in the day, the only people who would touch art were the Italians and now everyone is doing it,” said Bonvicini. “At the same time museums are changing too because they need more numbers of visitors, so there are DJ sets and yoga Fridays. At the end of the day, the question is who is the public? Though for me is a huge luxury when I can go to a museum and be alone in a gallery.”

“Put all Heaven in a Rage” is on view until October 12 at Tanya Bonakdar.