Art World

Christian Monk Grigorios Sinaite Fights Intolerance with Art at St. Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai

Are paint brushes more powerful than bullets? Sometimes, yes.

Are paint brushes more powerful than bullets? Sometimes, yes.

Daria Daniel

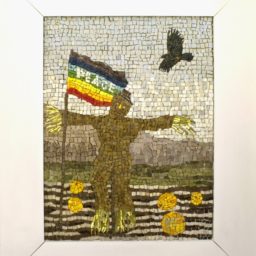

“My brushes are stronger than terrorists’ RPG’s and my tesserae are mightier than their bullets,” Monk Grigorios Sinaite affirms over our e-mail correspondence.

Joseph Toufic El-Jamous, or monk Grigorios Sinaite, has lived at St. Catherine’s Greek Orthodox monastery in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula for almost 20 years. He is one of 25 monks who call the monastery home.

artnet News spoke to El-Jamous, a monk of Greek and Lebanese descent, who has long turned to art for reprieve, and now, to eclipse surrounding extremism in the central southern province of the Sinai. He calls art his “daily bread.”

“Art is an ideal mean to oppose war, fanaticism and hatred,” explains Monk Grigorios. “I concur with [Fyodor] Dostoyevsky that ‘beauty will save the world,’ […] so peace and love can conquer tyranny and terrorism.”

St. Catherine’s monastery is recorded in the Old Testament as the place where God bequeathed to Moses the Tablets of the Law. After 17 centuries, it is the oldest, uninterruptedly inhabited Christian Monastery in the world.

The Byzantine religious shrine also joins the spiritual ranks of the Old City of Jerusalem: multilaterally sacred in Christianity, Islam and Judaism.

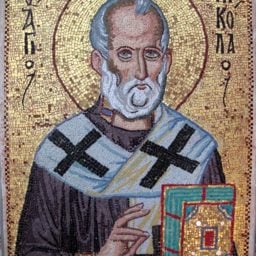

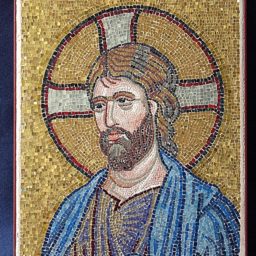

Monk Gregory takes great pride in the Helleno-Roman relics at St. Catherine’s. The monastery houses some of the earliest and most rare Christian manuscripts and Byzantine icons. “I live the Sinaitic heritage of icons and mosaics by meditating our great and exceptional collection almost every day,” he has relayed.

Joseph Toufic El-Jamous’ work is very much anchored in the tradition of old mosaic masters, especially those painted between the 12th and 14th centuries—and he emulates these archetypes handsomely. “Such mosaics are diachronic and eternal, [they] can never become obsolete,” the mystic-artist explains. He studied iconography and mosaics both in the Middle East and in Europe, painting at Liceo Artistico de Nittis in Bari, Italy and receiving numerous prestigious international awards.

***

At a time of heightened awareness for the future of Christians in the Middle East, monk Grigorios’ dedication is nothing short of heroic.

The monastery previously suffered from political rifts in the region following the resignation of former president Hosni Mubarak in 2011 and subsequent ejection of former President Mohamed Morsi, during the July 2013 “second revolution” that left Abdul Fatah Al Sisi in power. It was closed for a few months for fear of extremist Muslim reprisals against Christian places of worship. (As a precautionary measure, the monks even took to digitizing their biblical scripts to protect their preeminent collection of Christian texts).

Historically however, the Christian community of St. Catherine’s has enjoyed friendly relations with Islam. The Actiname, a document signed by Prophet Muhammed in 623, calls upon Muslims to support the monastery. During the Fatimid Caliphate, the monks allowed for the conversion of a refectory within the monastery’s walls to a mosque that still stands today and since its inception, St. Catherine has remained under the unofficial protection of Islamic Bedouin families of the surrounding Jebeliya tribe.

Gregory Sinaite’s artwork, for its beatific qualities and the symbolism behind his gestures, is invaluable.

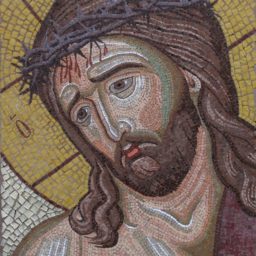

His most impressive pieces come in the form of beautiful modern and traditional mosaics. Monk Gregory explores themes of hypocrisy and time, while separately depicting Christ and St. Catherine in a traditional Orthodox style. A striking work, “Blessing Hand of the Lord” on an agate slab, is emblematic of his combined culture, a Pharaonic bracelet accompanies a Christian Orthodox hand gesture.

While his art reflects a respect for tradition, Monk Grigorios also embraces forms of modern art. He draws an interesting correlation between Byzantine and Impressionist art: “Byzantine art is based on the idea of divine light emanating from the Kingdom of Heavens […] Impressionists based their art on the idea of light existing everywhere.”

Experimenting with different styles and media, Monk Grigorios’ range includes acrylic, oil painting, gouache and mosaics. Particularly inspiring is his depiction of the fall of Icarus, shown tumbling to the sea under the guise of a forewarning father. “The Fall of Icarus has always enchanted me […] people can apply these mythologies to modern life and in doing so, enrich their personal experiences.”

***

For all of its aesthetic appeal, Monk Gregory’s artwork is symbolically far-reaching. His commitment to artistic creation and defense of this liberty should not go unheeded.

He describes his situation at St. Catherine’s as both a “special blessing” and a “war of survival.” “[It has] inspired me to continue my creativity against all odds, because, in the end, creativity is divine […] I participate in artistic resistance by continuing my art.”

Woeful times in history have called for artistic creation—either art that responds to tragedies or art kindled as a coping mechanism. Such creative contributions, like those offered by Monk Gregorios, are both courageous and imperative.

When asked if he had left the monastery since recent political developments in the Sinai, he responds, “the monks of the monastery never considered deserting the monastery, even for one day, and I feel honored to be standing with them.”