“I don’t know where the artificial stops and the real starts,” Andy Warhol once said.

In a gesture that the artist himself would have likely endorsed, the art and design collective MSCHF has purchased an early sketch by Warhol, created 999 exact replicas, and then mixed all the artworks altogether, effectively rendering the original indistinguishable from the facsimiles. Starting today, they’re selling them for $250 a pop.

Put that money down and you have a 0.1 percent chance of scoring a genuine Warhol worth $20,000. (That’s what the group paid for it, at least.) But here’s the twist: you’ll never actually know if you got the real thing.

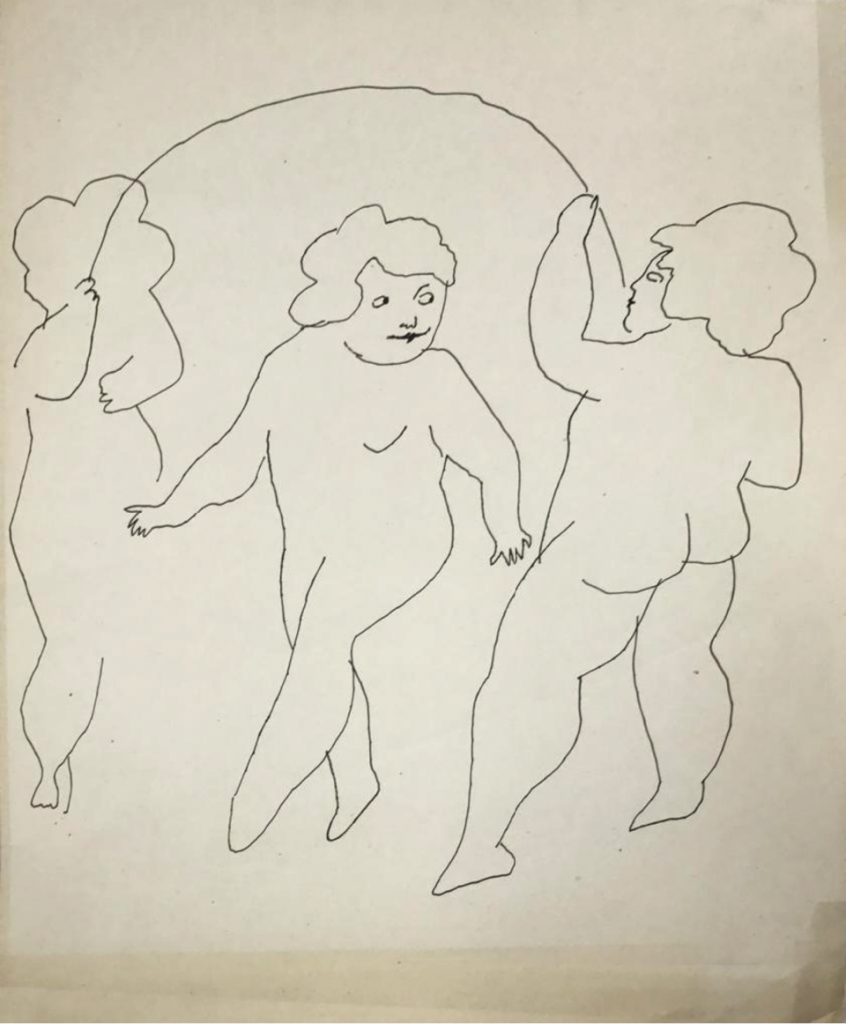

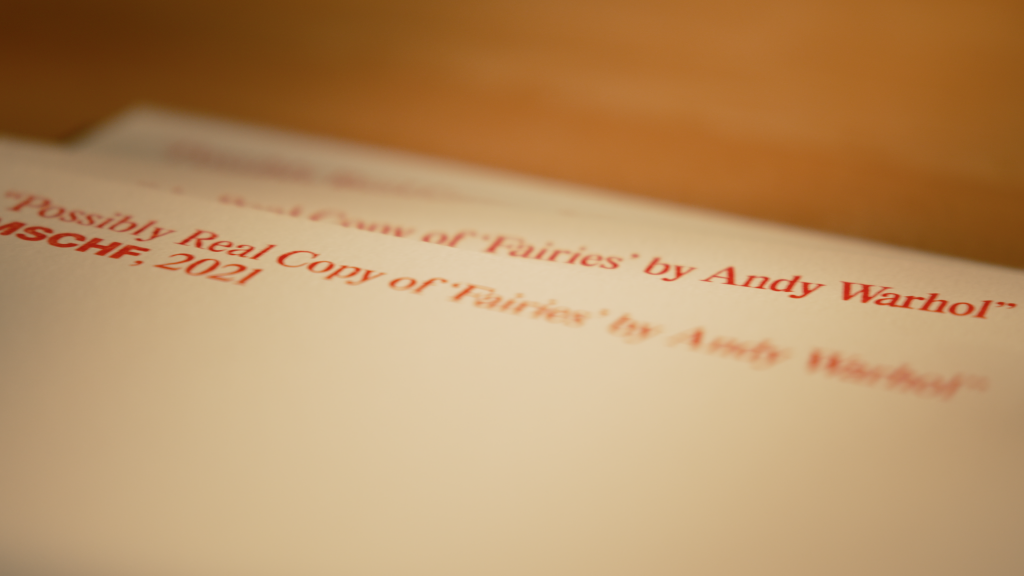

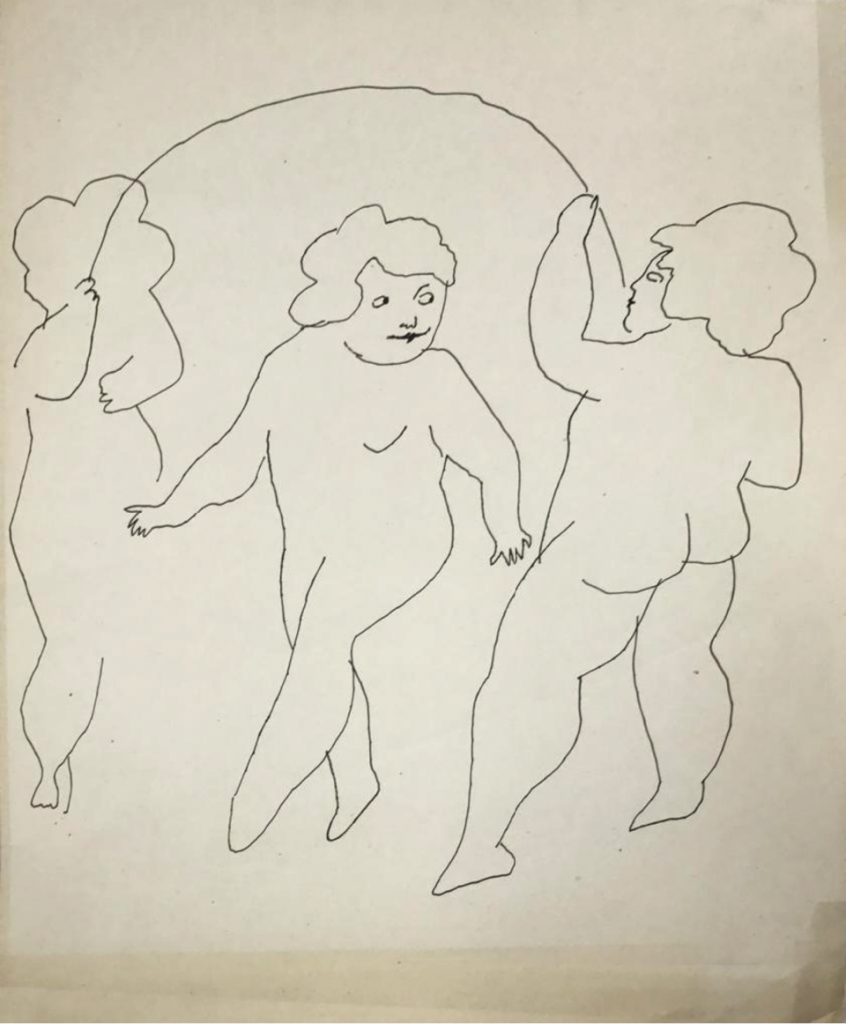

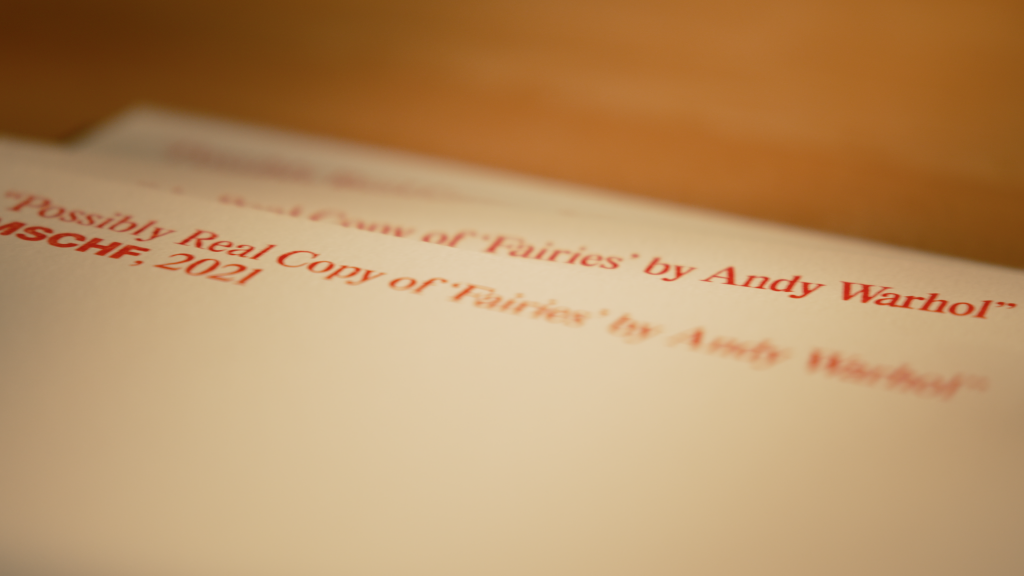

MSCHF, Possibly Real Copy of ‘Fairies’ by Andy Warhol (2021). Courtesy of MSCHF.

That’s the rub behind Museum of Forgeries, the newest drop from the sardonic group known for cutting up a pricy Damien Hirst print, making paintings from medical bills, and mainlining their members’ own blood into custom Nikes. (The collective’s name is pronounced, aptly, “Mischief.”)

“By forging [Warhol’s drawing] en masse, we obliterate the trail of provenance for the artwork,” the collective explained in a statement. “Though physically undamaged, we destroy any future confidence in the veracity of the work.”

In other words, MSCHF’s description goes on, “by burying a needle in a needlestack, we render the original as much a forgery as any of our replications.”

A MSCHF member at work on the Museum of Forgeries. Courtesy of MSCHF.

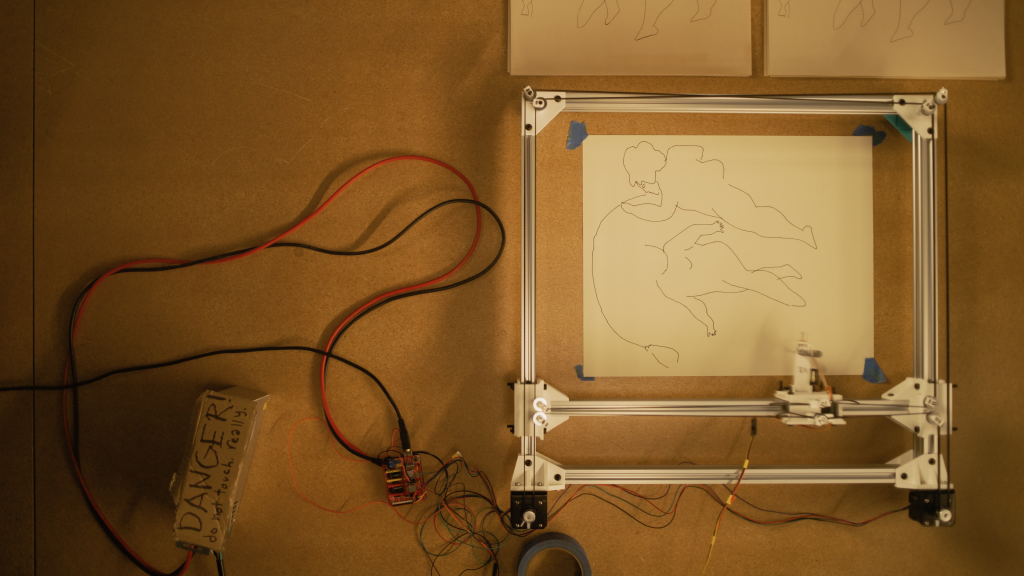

Completed by Warhol in 1954, the minimalist 13- by 16-inch ink drawing depicts three fairies playing jump rope. After MSCHF purchased it from Hamilton-Selway Fine Art in Los Angeles, they built a custom robot to create copies and then artificially aged and stained each piece of paper.

Each drawing comes with two certificates of authenticity—one for Fairies by Andy Warhol, and another for Possibly Real Copy of ‘Fairies’ by Andy Warhol by MSCHF. (Both certificates were made by the collective and none is associated with the Andy Warhol Foundation. The foundation did not immediately respond to a request for comment about the project.)

“Warhol is a key point in the canon of art intermeshing with mechanical reproduction,” MSCHF chief creative officer Kevin Wiesner told Artnet News. “He mainstreamed the idea that great artists don’t produce their own works themselves, which at some point farther back in history would have been as verboten as forgery.”

“For us,” Wiesner continued, “Museum of Forgeries is about using duplication as a means of destroying art.”

Courtesy of MSCHF.

As is the case with many of MSCHF’s efforts, it’s difficult to tell if what they’re after here is some kind of pseudo-conceptual artwork unto itself or simply an elaborate troll job. (Warhol knew that gray area well; Richard Prince lives there to this day.) Nevertheless, the project does raise an interesting question about shifting market values: In today’s age of brand building, what means more, exclusivity or merchandising?

“Merching down is how blue-chip artists actually generate reliable profits,” Wiesner explained. “Auction results on Spot paintings don’t pay Damien Hirst, but they do create a market he can tap by making prints.” (KAWS, he added, is an example of an artist “merching up.”) The question MSCHF is asking with their latest project is whether big public prices are a prerequisite to profiting off of one’s brand.

They may already have their answer: All of MSCHF’s previous projects with a “commerce component” have sold out, according to a spokesperson for the group. Only once has their work appeared on the block at a major auction house—and they consigned it themselves.