Politics

Museum Unions Aren’t Just Demanding Higher Pay. They’re Also Fundamentally Questioning the Way Their Institutions Work

"We are asking for a change on all fronts," one organizer at MOCA Los Angeles says.

"We are asking for a change on all fronts," one organizer at MOCA Los Angeles says.

Catherine Wagley

As a wave of unionization efforts has swept across the museum world, employees have faced plenty of pushback—one case in point being the New Museum’s hiring of a union-busting law firm during a recent labor struggle.

But no institution has responded with as much drama and chaos as the Marciano Art Foundation (MAF) in Los Angeles.

The MAF laid off all of its visitor-service associates in November, days after those employees announced their intention to unionize. Soon after, the entire foundation was shuttered for good. The protests, lawsuit, and press that followed have kept the MAF in an unflattering limelight.

In a lengthy Los Angeles Times report published in mid-February, Paul and Maurice Marciano, the brothers who started the denim brand Guess and then later founded MAF to showcase their art collection, came under scrutiny for, among other things, alleged labor law violations at Guess (paying under minimum wage or offering no overtime) and for making Maurice Marciano’s under-experienced daughter, Olivia, the artistic director of their foundation.

Exterior of the Marciano Art Foundation. Photo by Julian Calero.

The Marciano debacle was still fresh and unfolding when workers at MOCA Los Angeles and the Shed in New York moved to unionize. Both museums chose to voluntarily recognize their unions, rather than to campaign against them, a move that set them apart from other art institutions nationwide.

That decision surprised Maida Rosenstein, president of UAW Local 2110, the union that represents workers at the Shed as well as at MoMA, the Bronx Museum, the Tenement Museum, and the New Museum. “The more standard thing is for employers to fight unions, conduct anti-union campaign,” she said. “[They] try to use all the mechanisms to delay elections.”

An institution that voluntarily recognizes a union waives its right to insist upon an election, and to campaign against the union. Instead, an independent third party verifies that a majority of employees want to unionize.

Yet even when museums accept unionization efforts, negotiations don’t always proceed smoothly.

“Voluntary recognition, it’s a misnomer in a way,” explained Rosenstein.

“It’s rarely because they’re embracing a union,” she said. “You would hope… they would also be amicable at the bargaining table, but I don’t think that’s a given.”

She cited the neutrality agreement reached by the Tenement Museum and its union, which kept the museum from staging an anti-union campaign but did not keep it from taking hard positions in contract negotiations.

“I don’t think there’s been a significant change yet at this point,” she added.

The Shed preparing for open air performances. Photo by Sarah Cascone.

The Shed, a year-old, extravagantly designed art space in Hudson Yards, declined to comment for this story but issued a statement from COO Maryann Jordan in late January, saying, “We welcome UAW Local 2110 and anticipate forging a constructive relationship with their representatives.”

Senior organizer Carlos Vellanoweth, of AFSCME District Council 36 in Los Angeles, put it bluntly: “Employers recognize the union when they get their back against the wall.” AFSCME, which represents 16 museums nationwide, worked with employees at MAF and is now coordinating with those at MOCA Los Angeles.

Vellanoweth, who helped MOCA’s union through the initial stages of the organizing process, suspects that the protests at MAF contributed to MOCA’s administration taking a different tack. “I think that they have a lot more to lose than a private museum that is run by two gentlemen,” he observed, referring to the Marciano brothers.

Indeed, MOCA agreed to enter contract negotiations right away. But when employees first announced their unionization effort, MOCA released a statement to the Los Angeles Times, saying, “we do not believe that this union is in the best interest of our employees or the museum.” After more careful consideration, the museum walked back that statement.

“We are, of course, aware of what is happening in the field and the world more broadly,” a MOCA spokesperson told Artnet News. “That said, MOCA’s decision to voluntarily recognize the union was driven by the belief that it was the right thing to do for our employees and is in alignment with our mission as a civically minded institution.”

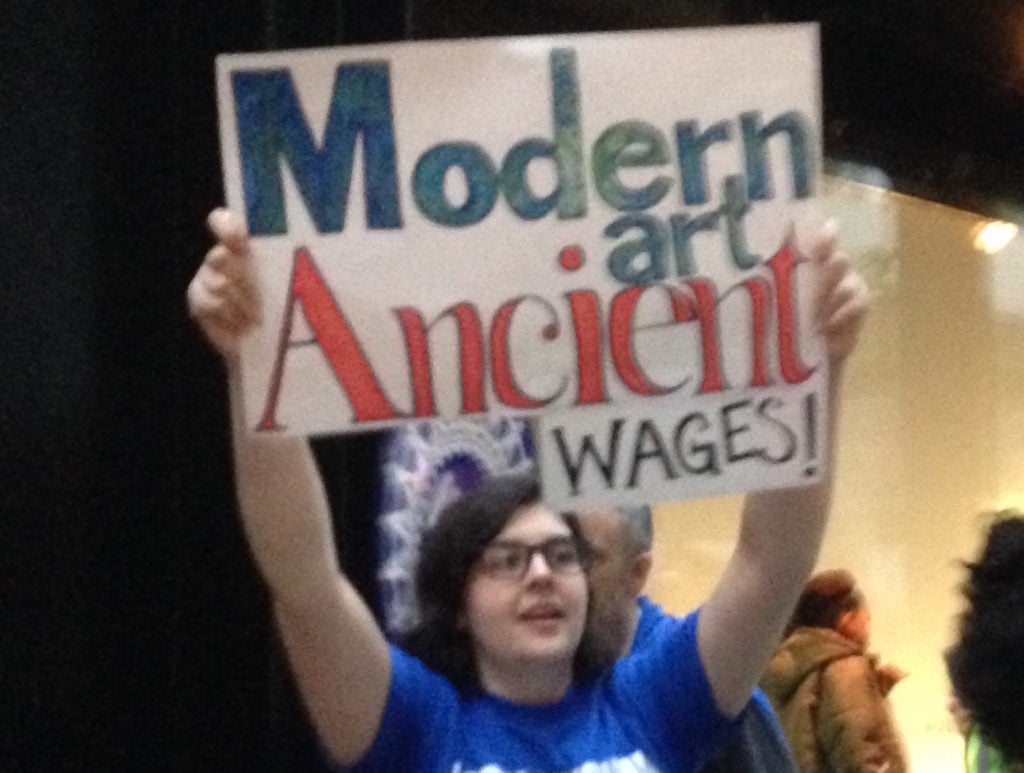

A union member protests outside MoMA’s Party in the Garden on May 31, 2018. Photo by Sarah Cascone.

The spokesperson also pointed out that MOCA began “the process of evaluating and improving issues of Diversity, Equity, Accessibility and Inclusion (DEAI)” over eight months ago, an effort helmed by Mia Locks, the newly appointed Senior Curator and Head of New Initiatives.

The museum also brought in an outside consultant to identify improvements to workplace structure and culture.

“MOCA had met requests from our frontline staff for internal negotiations this fall,” MOCA’s spokesperson explained. “Following these discussions, wages were increased prior to receiving any notice from the union.”

Organizing committee member Lauren Kelly acknowledged that, while some internal changes had been made in response to employee concerns, “we were meeting with AFSCME before this.” She explained that the unionizing effort at MOCA was, from the start, about both pragmatic changes and ideals that went beyond the museum’s walls.

“The issues we’ve encountered ripple across many of these institutions, and we are asking for a change on all fronts.”

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Education Images/Citizens of the Planet/UIG via Getty Images.

Committee member Junghun Lee concurred. “We welcome the administration’s effort to make the museum a better workplace, but we ultimately see our role within the effort [as] more involved and direct,” he said.

Organizers pointed out that not all employees have received wage increases, and that they are interested in improving conditions for part-time museum workers at MOCA too, as well as establishing clearer paths for workers to reach full-time status and receive benefits.

They hope these changes can ripple out across the wider industry. Certain part-time MOCA employees work for more than one local museum, and some were among those laid off from MAF.

Another MOCA organizer who wished to remain anonymous further contextualized their efforts.

“We felt that real change would only come when the balance of power shifted towards those who see the labor issues at the museum first-hand,” the person said, explaining that the museum has a history of “reneging on promises or moving at a glacial pace when it came to structural changes.”

Unionizing is a way to ensure that promises are kept, the person said.

“Ultimately, though, we are combating the museum model. In the weird public/private hybrid model of the museum, there is seemingly unlimited money made in donations for the building and for artwork, but a millionaire or billionaire is never going to swoop in to provide changes to wage structure or employee safety.”