Archaeology & History

Archaeologists Say a Mystifying Group of Ancient Monuments in Saudi Arabia Suggests the Existence of a Prehistoric Cattle Cult

The massive monuments were built at a time when the land was covered in verdant green plantlife.

The massive monuments were built at a time when the land was covered in verdant green plantlife.

Sarah Cascone

A mysterious group of ancient monuments first discovered in Saudi Arabia in the 1970s, known as mustatils, predate the first Egyptian pyramids and Stonehenge by over 2,000 years, making them the world’s oldest ritual landscape, archaeologists now say.

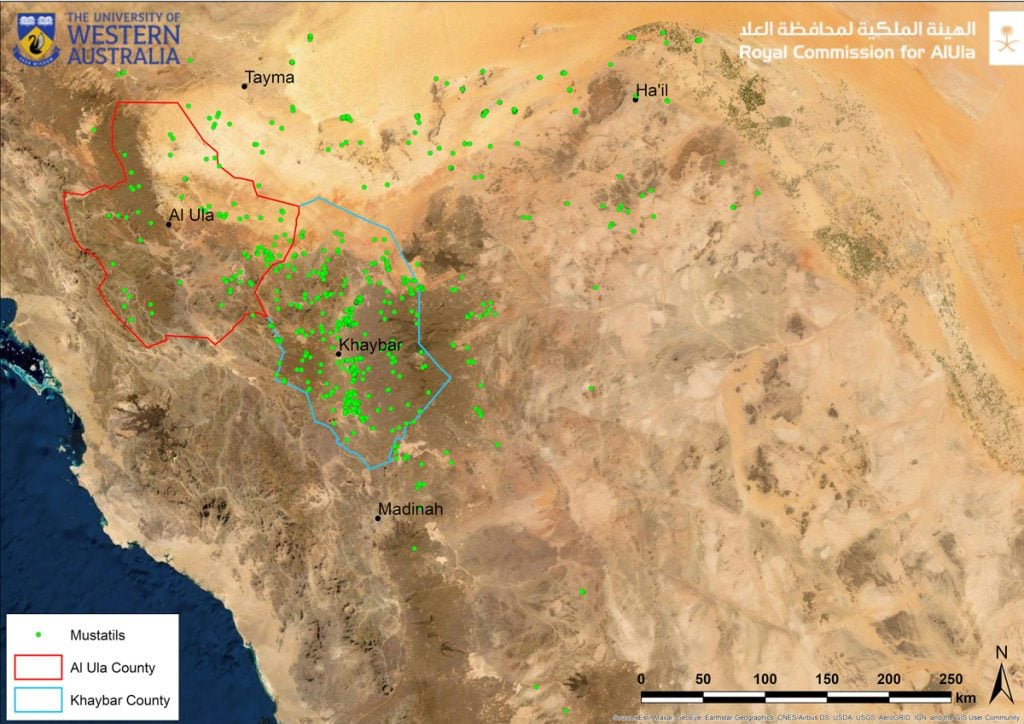

Scattered across 77,000 square miles of desert in northwest Arabia, the mustatils (the name comes from the Arabic word for “rectangle”) were built between 8,500 and 4,800 years ago, during the period known as the Middle Holocene, according to a report published last week in the journal Antiquity.

Through satellite imagery, helicopter and ground surveys, and excavations, the study identified more than 1,000 mustatils, typically built in clusters. That’s more than double the number previously thought to exist.

The project, led by a team from the University of Western Australia, is being funded by the Royal Commission for AlUla, which is hoping to drive tourism to the nearby site of AlUla.

Experts had previously raised numerous theories as to the structures’ purpose, including as animal enclosures, burial sites, or territory markers. But the new study shows that the mustatils’s walls would have been too low to prevent animals from escaping.

The locations of mustatils in northwest Saudia Arabia. Image courtesy of the Royal Commission for AlUla.

“You don’t get a full understanding of the scale of the structures until you’re there,” archaeologist Hugh Thomas, the director of the project, told New Scientist. “It’s not designed to keep anything in, but to demarcate the space that is clearly an area that needs to be isolated.”

Archaeologists found animal bones on the sites, which seem to be the remains of religious offerings. The presence of cattle skulls in particular suggests the existence of prehistoric cattle cult.

“We think people created these structures for ritual purposes in the Neolithic [era], which involved offering sacrifices of wild and domestic animals to an unknown deity/deities,” Thomas told the Art Newspaper.

A cattle horn found at a mustatil, suggesting ritual sacrifice. Photo courtesy of the Royal Commission for AlUla.

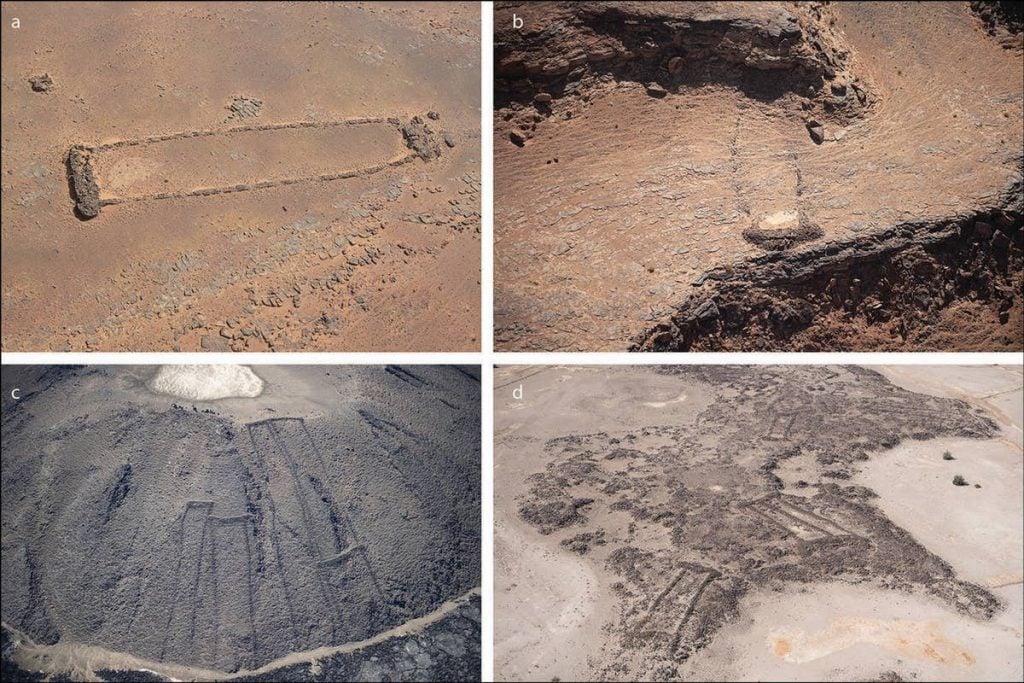

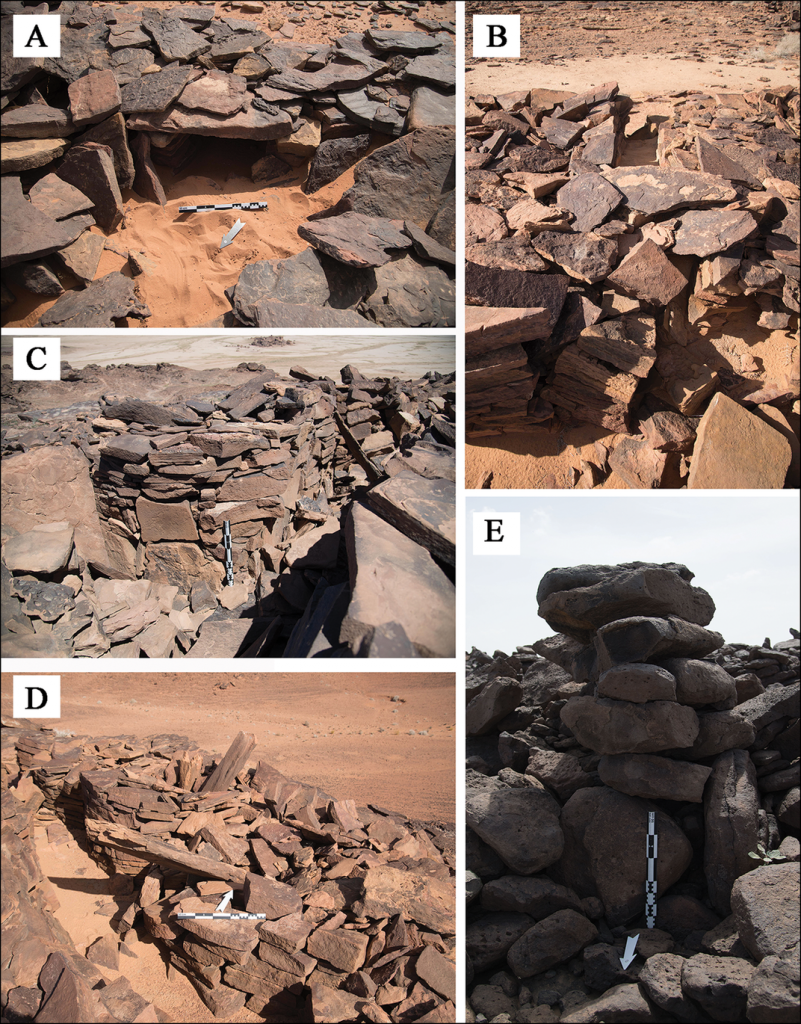

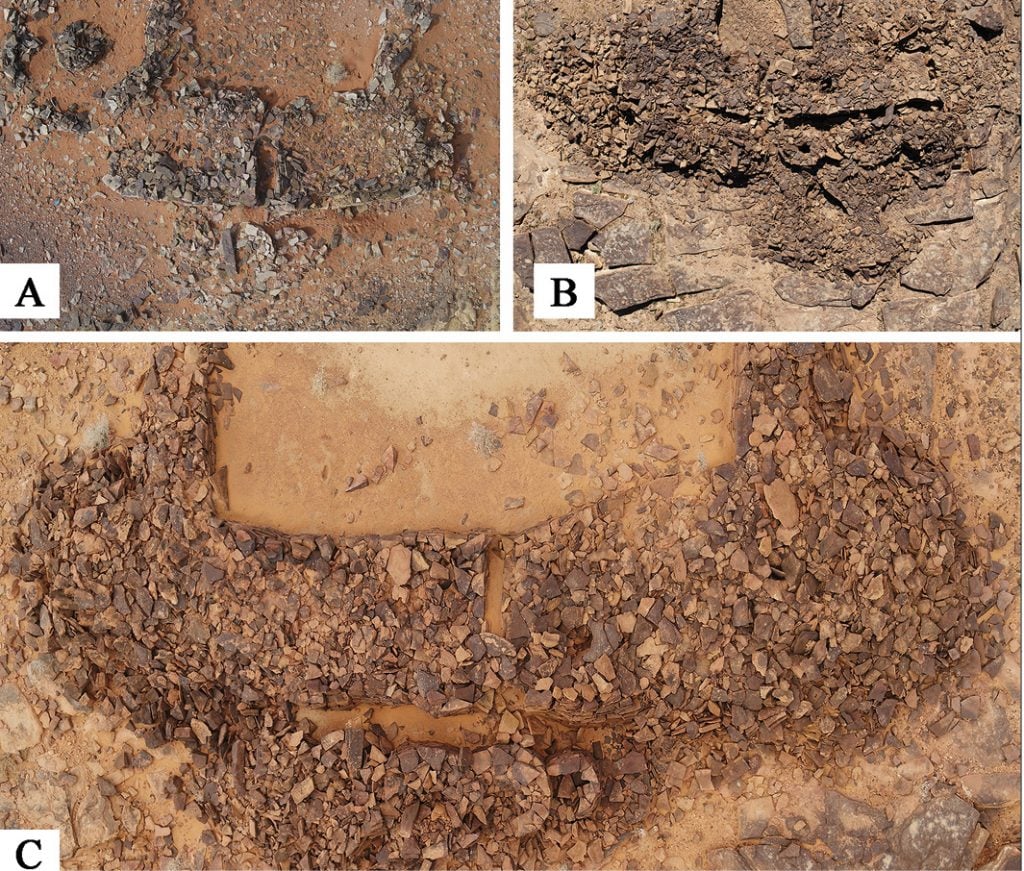

The largest mustatils are more than 1,500 feet long, with one example constructed from 12,000 tons of basalt stone. Some are simple constructions, with low rock walls forming long rectangles. But others are far more complex, with pillars, interior walls, and small chambers that may have been used for ritual sacrifices.

During the construction of the mustatils, Saudi Arabia would have been all but unrecognizable to contemporary eyes, a verdant green landscape where there is now arid desert.

“The environment was certainly much more humid during this period,” Melissa Kennedy, assistant director of the Aerial Archaeology in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia project, told Live Science. “Cattle need a lot of water to survive.”

Three mustatils. Photo courtesy of the Royal Commission for AlUla.

But there were also periods of drought, suggesting the ancient people who built these structures may have been making offerings asking for rainfall, which is essential for raising cattle.

“These thousands of mustatils really show the creation of a monumental landscape,” Huw Groucutt, an archaeologist at Germany’s Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History who has separately studied mustatils, told NBC News. “They show that this part of the world is far from the eternal empty desert that people often imagine, but rather somewhere that remarkable human cultural developments have taken place.”

The Royal Commission for AlUla will showcase mustatils at the Kingdoms’ Institute, an international archaeology and conservation center that is among 15 cultural institutions the nation is planning to establish.

“We have only begun to tell the hidden story of the ancient kingdoms of North Arabia,” José Ignacio Gallego Revilla, executive director of archaeology, heritage research, and conservation for AlUla, said in a statement. “There is much more to come as we reveal the depth and breadth of the area’s archaeological heritage, which for decades has been under-represented.”

See more photos from the study below.

A number of mustatils. Photo ©Aerial Archaeology in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Royal Commission for AlUla.

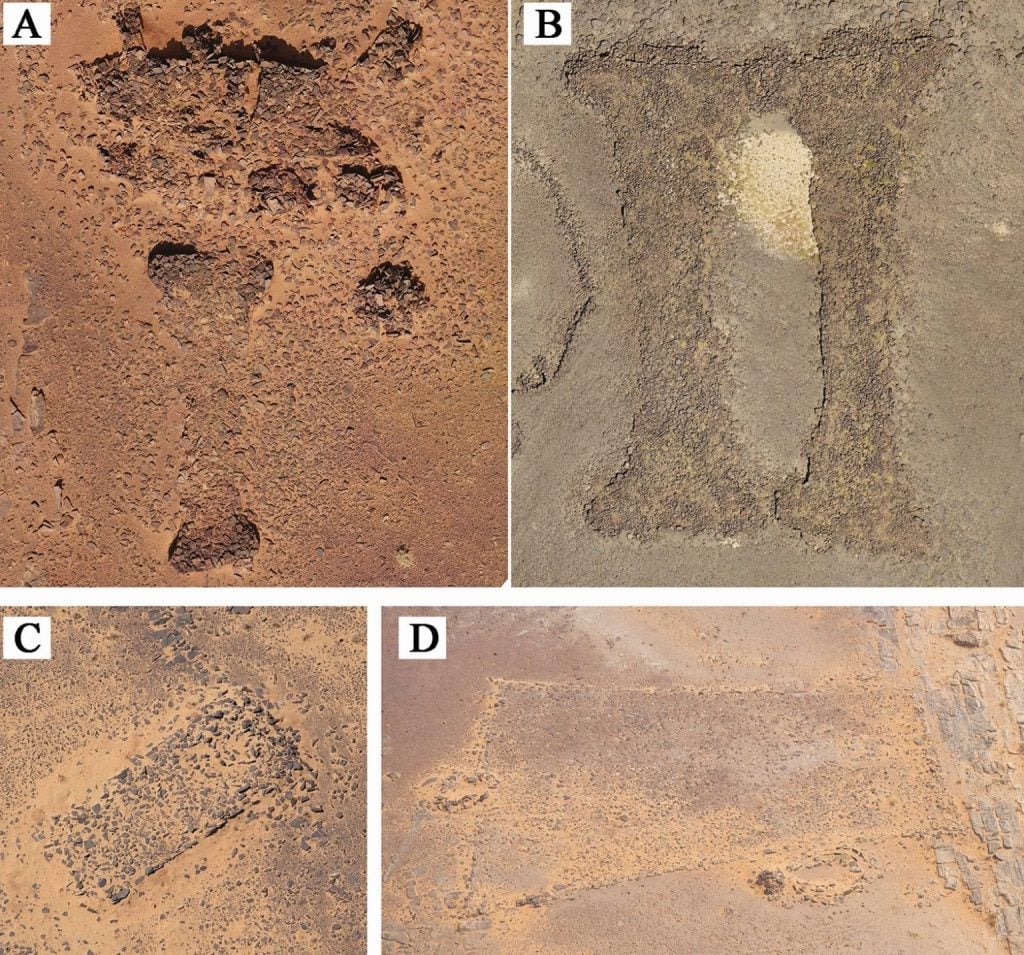

A) internal niche located in the head of a mustatil; B) a blocked entranceway in the base of a mustatil; C–D) associated features of a mustatil: cells and orthostats; E) stone pillar identified on the Harrat Khaybar lava field. Photo ©Aerial Archaeology in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Royal Commission for AlUla.

A group of mustatils. Photo ©Aerial Archaeology in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Royal Commission for AlUla.

Two mustatils. Photo courtesy of the Royal Commission for AlUla.

Some mustatils in northwest Arabia. Photo ©Aerial Archaeology in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Royal Commission for AlUla.

Three monumental mustatils and a later funerary ‘pendant’ located atop a rocky outcrop on the border of Khaybar and AlUla counties. Photo courtesy of the Royal Commission for AlUla.

A mustatil. Photo courtesy of the Royal Commission for AlUla.

Some mustatils in northwest Arabia. Photo ©Aerial Archaeology in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Royal Commission for AlUla.