A chatty crowd of people holding wine glasses milled about Goldsmiths, University of London, standing on piles of torn images. The exchanges among the seemingly cheerful group belied the seriousness of the artwork, on view in a solo exhibition titled “Please Enjoy Our Tragedies,” which documents the bleak final hours before a Burmese artist’s dangerous escape from Myanmar in May 2021 after a bloody military coup.

“This is my hello and my goodbye,” the anonymous artist behind the artwork, who goes by Sai, told Artnet News. “I want to try to reach out to people, to show them the evidence of what’s happening [in Myanmar]. Do people here give a fuck? Not really. But they give a fuck when art is rooted in tragedy, and hence the title of the show.”

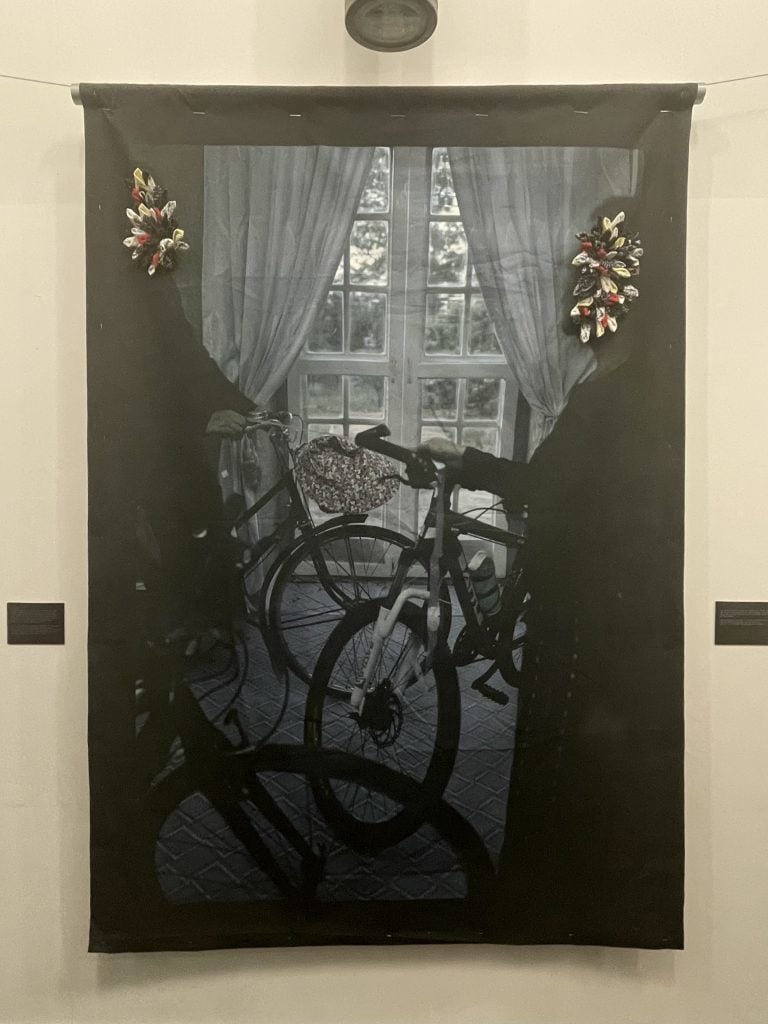

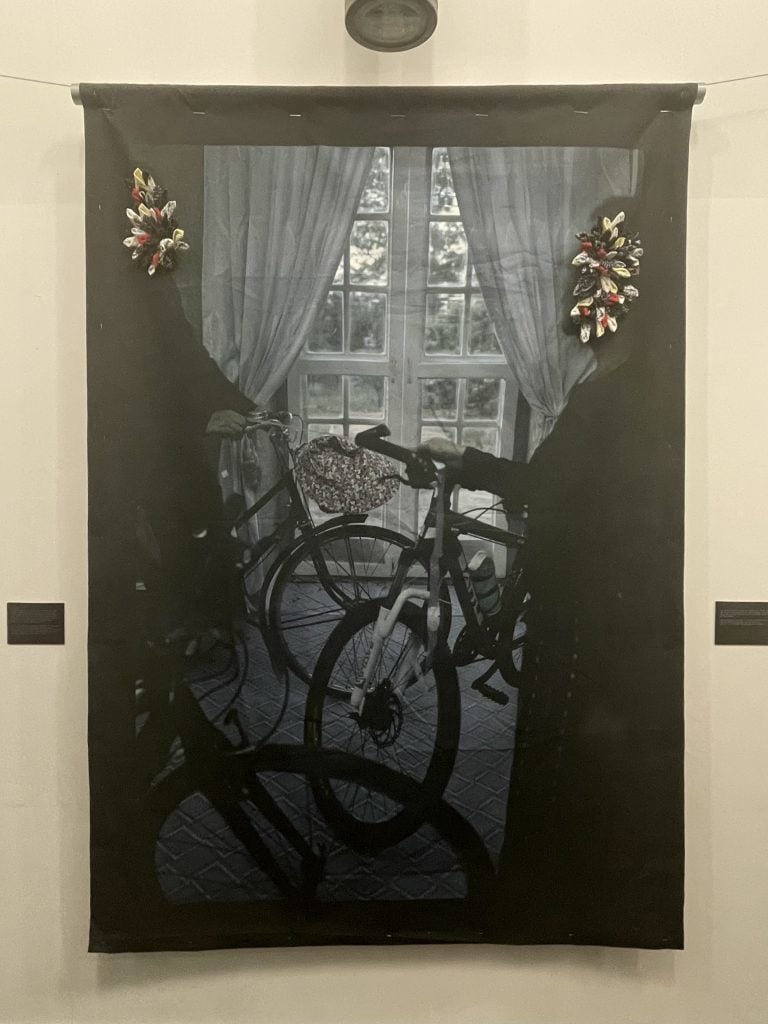

“Mom was hoping that dad would be released soon,” the artist said. Photo by Vivienne Chow.

Sai, which means mister in the Shan language, said he cannot reveal his full name for safety reasons. His father, Linn Htut, was the chief minister of the Shan state in Myanmar and was a member of the now-jailed former leader Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy, which was ousted during the February 2021 coup.

Linn Htut was since sentenced to 16 years in prison on four separate counts of corruption. Sai’s mother is living under 24-hour surveillance.

Sai, who studied at Goldsmiths on a fellowship in 2019, must soon bid farewell to the U.K.: his visa expires in May. Should he choose to return to Myanmar, his life may be at risk.

“My father may die, regardless of what I do,” he said. “My mother may die. I may die. But before that, we have to let people know that this has happened.”

Initially, he planned to campaign on his family’s behalf outside the country. But after trying to reach different human rights organizations and British members of Parliament, he said he felt like his cause had become hopeless.

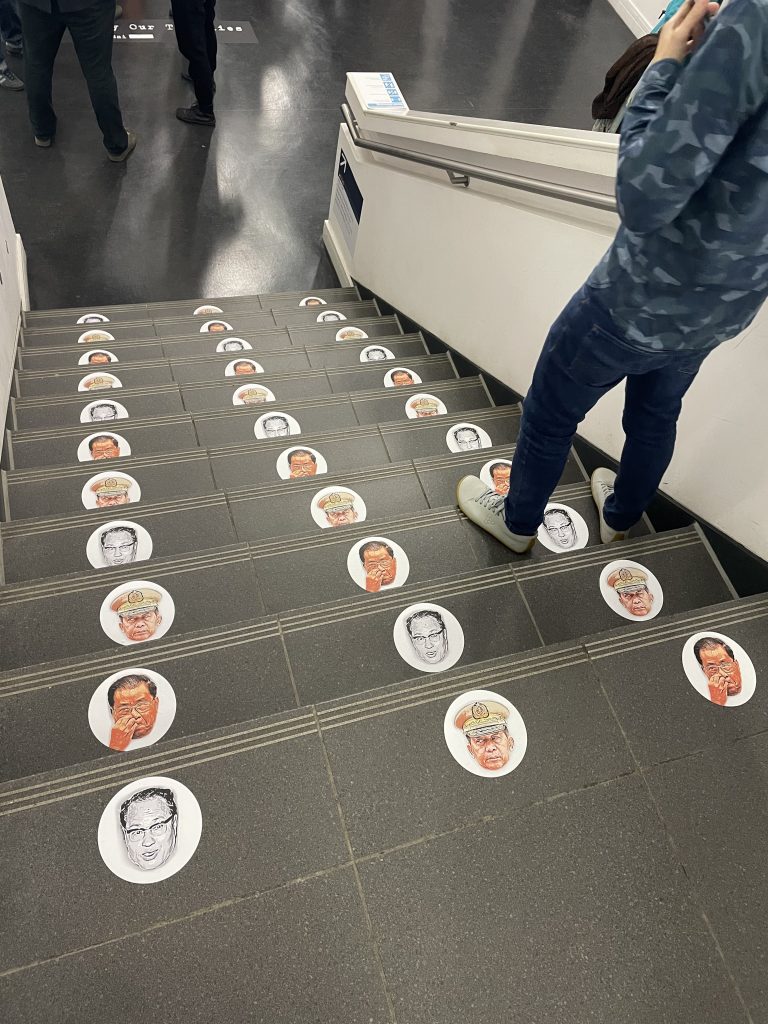

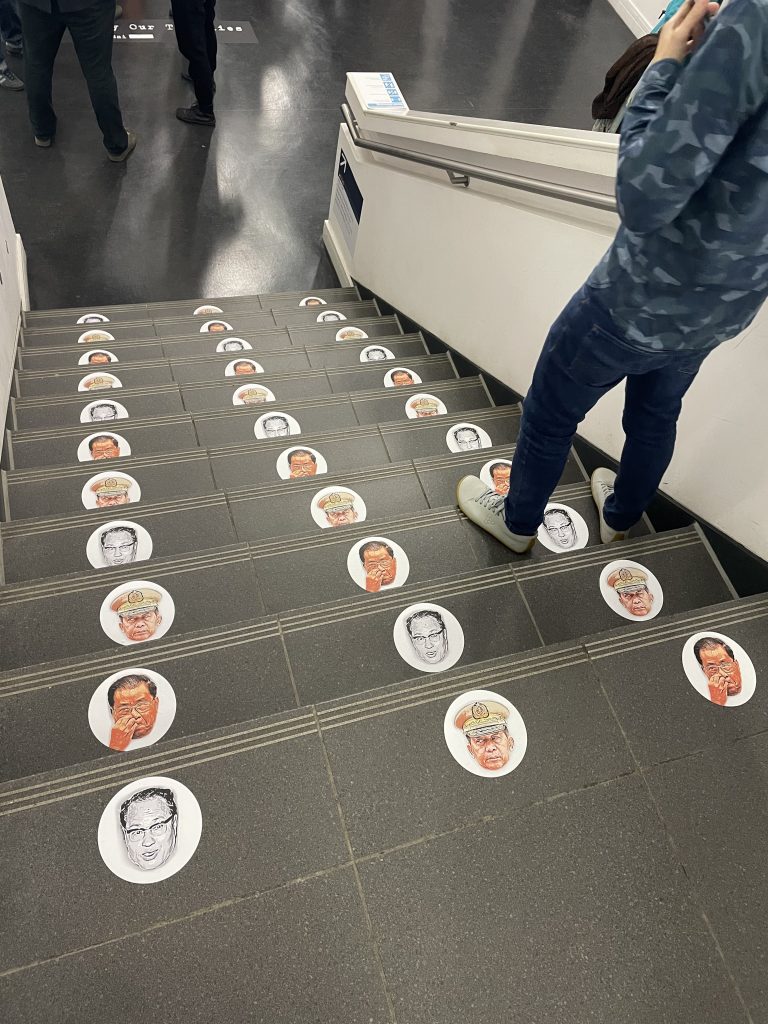

Faces of Mynamar dictators on the floor. Photo by Vivienne Chow.

According to the latest United Nations human rights report published this week, the junta has been suppressing resistance violently. Those who have been detained have been tortured, suspended from ceilings, injected with drugs, or subject to sexual violence. Nearly 1,700 people have been killed since last year, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners.

“Atrocities happen every day. Villages are burned, women are being raped, children and babies are killed,” Sai said. “But still, our tragedies are disposable.”

The works on display mirror this narrative. Included are large-scale images and a video that Sai took of his seized family residence in Taunggyi in northern Myanmar, just before he fled the country.

The images are torn, piled up, and discarded on the floor. Beneath them are the exact same images, ripped from gallery walls.

“That’s why you see them lying on the floor. That’s how we are treated,” Sai said. “Everyone shoved us under the carpet. An image may have been torn, but it is still there.”

Sai said the display was inspired by movie posters: when a theatrical release period is over, they are taken down and replaced with posters for new releases. The artworks are accompanied by installations reflecting on the military’s economic empire and fabric sculptures made of political prisoners’ clothing.

“The fabrics that cover our faces are woven in the style of a traditional Shan carpet, created from the clothes of political prisoners abducted by the regime,” the artist said.

Sai said his ongoing series, “Trails of Absence,” is expected to be included in the European Cultural Center’s group show, “Personal Structures,” at Palazzo Bembo during the Venice Biennale.

But whether he will be in attendance isn’t his primary concern.

“I can’t be depressed,” he said. “Maybe one day I will be broken into pieces. But now I’m like a broken machine, and I can only keep going.”