Art & Exhibitions

Nan Goldin’s ‘Ballad of Sexual Dependency’ Lights Up MoMA

A chronicle of history that helps us grieve the tragedies of the present.

A chronicle of history that helps us grieve the tragedies of the present.

Christian Viveros-Fauné

I don’t remember when I first saw Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, her 1980s East Village rendition of La Boheme, but I recall exactly what it felt like: It was as intense as an earthquake, as personal as a starter tattoo, as wrenching as a childhood bellyache.

Sitting through Goldin’s 700-image slideshow felt, I realized just days ago, not unlike waking up to news of another mass shooting. Virtually overnight, people whose youth had been electric with possibility were cruelly no longer in the picture. Meantime, their photographic likenesses morphed from simple snapshots into something else: portraits that turned elegiac, hopeful, monumental even.

The victims of Orlando’s Pulse nightclub will be in the public eye as long as certain false impasses in politics remain conveniently unresolved. The dead and wounded of Goldin’s time-lapse film, on the other hand, live on in the artist’s portrait of downtown New York at the height of the AIDS crisis. The Ballad of Sexual Dependency currently materializes a stubborn if unerring cliché: ars longa vita brevis. Would that every major generational tragedy had a memoirist like Nan Goldin.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of Marian and James H. Cohen in memory of their son Michael Harrison Cohen. © 2016 Nan Goldin

On view until February 12, 2017, as a dedicated installation at MoMA’s second floor galleries, Goldin’s latest version of Ballad—the artist has continually altered the work since its first showing in 1980 at the legendary “Times Square” exhibition—is as searing as ever. The work consists of a set of portraits Goldin took of her own and her friends’ high-risk lives during the late 1970s and ’80s, and their steady progress across a museum wall makes for mesmerizing viewing. Goldin once characterized the Ballad as “the diary I let people read.” It remains, she wrote in her bestselling Aperture book by the same name, “my form of control over my life. It allows me to obsessively record every detail. It enables me to remember.”

Developed through multiple improvised live performances in bars, clubs, screening rooms, and galleries, Goldin’s slideshow—to quote America’s first female Presidential nominee—took a village. Initially, the artist sifted through slides by hand; her friends suggested tunes for the soundtrack. At the time, the work’s audience was largely made up of the pictures’ subjects. Twenty-six years on, the Ballad is presented in its original 35mm format at MoMA to a vastly different crowd. Gone are many of Goldin’s original pals—lost to AIDS, addiction, and natural attrition. In their place stand museum tourists. To watch them avidly consume Goldin’s unfolding narrative is to witness far flung strangers get junkie hooked on the heroin that is New York’s last bohemia.

Courtesy: The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of Jon L. Stryker. © 2016 Nan Goldin

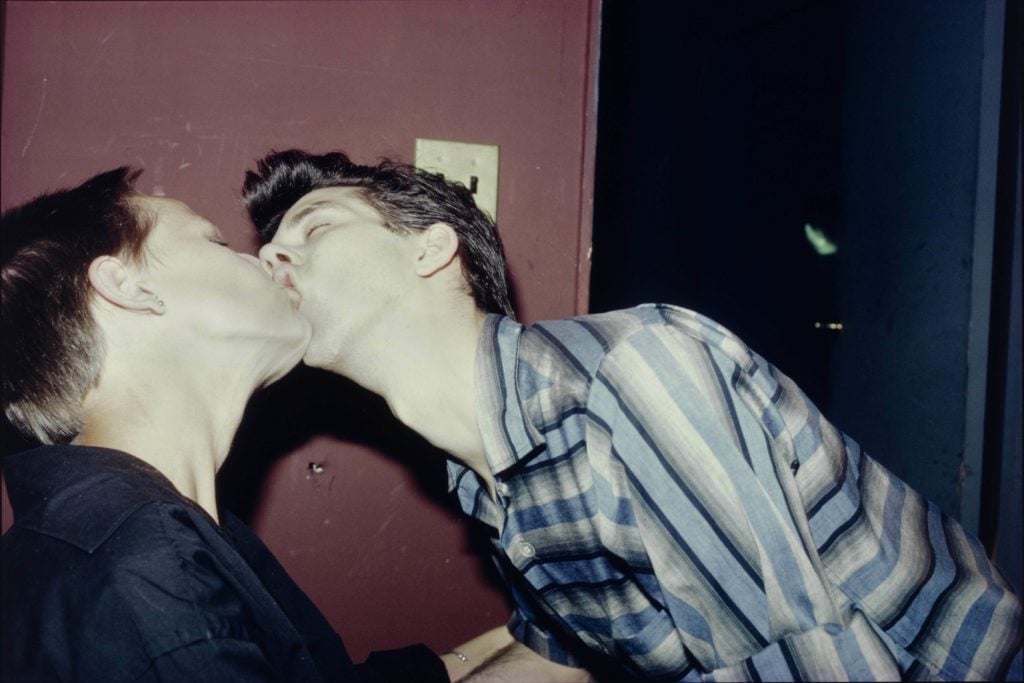

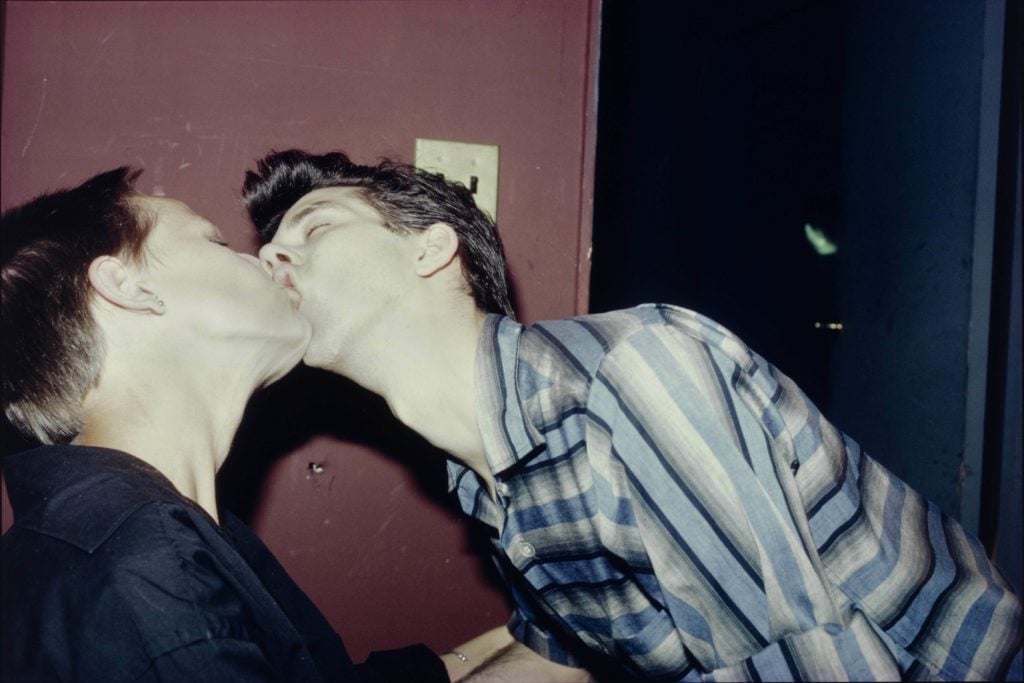

And what a romantic time it was, that era Goldin chronicled in photos of various daredevil lifestyle experiments played out in that alternate reality called downtown. Introduced in a first room by a single row of 17 photocopied posters that once advertised the Ballad and a vitrine containing mock-up pages from the Aperture book, the exhibition opens up into a second room containing 15 matching prints from the museum collection. All of these images appear momentarily in Goldin’s slideshow, but two stand out for their lovesick violence. In one, an androgynous couple locks lips with tooth-chipping recklessness. The second is a straightforward Goldin self-portrait: In it, she stares directly at the camera, lips rouged and brown ringlets framing a face ferociously punched in by a lover, Brian, who features prominently in the photo essay.

“The photo of me battered,” Goldin writes in the Aperture book, “is the central image of the Ballad.” And so it proves inside MoMA’s black box installation, where it is painfully echoed by several more images of a bruised Goldin. But if the artist’s lacerated self-portrait serves as a pivot for her celebrated carousel of snapshots, it does so, among other reasons, to trumpet the artist’s shared drama of immersion: Several hundred equally fierce images swirl antically around that hinge.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase. © 2016 Nan Goldin

Since the 1980s, Goldin has organized the photos in the Ballad around certain loose visual themes. They are summarized here by the following incomplete taxonomy. There is, for starters, a section that depicts women and men getting ready to go out; another features women and men of various sexual inclinations carousing at parties; a third portrays the effects of violence meted out to them; a fourth records uninhibited sex; a fifth captures cherubic children born from these entanglements; eventually, photos of intravenous drug use flash on the screen; finally, Goldin presents images of several of her subjects in coffins, followed by two graffiti skeletons embracing.

The effect is heart stopping. Goldin’s flickering images are scored to songs like Screaming Jay Hawkins’s “You Put Spell On Me” and the Velvet Underground’s “All Tomorrow’s Parties.” In the Ballad, they all sound like dirges.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase. © 2016 Nan Goldin

Rendered in vibrant color and captured with the spontaneity of a full-fledged participant, Goldin’s Ballad of Sexual Dependency is a record of loss that, like Puccini’s “La Bohème,” contains its own partial redemption. A mix of beauty, horror, and despair, her images also reveal a lust for life rare not just in art, but in living. A better memorial does not exist for alternative scenes anywhere—from New York’s faded downtown to today’s battered but unbeaten gay Orlando.