Art World

Smithsonian Curators Have Been Planning a Show About the History of Disease for Months. They Say They’re Not Surprised by the Current Pandemic

The exhibition will highlight US outbreaks of yellow fever, smallpox, and cholera.

The exhibition will highlight US outbreaks of yellow fever, smallpox, and cholera.

Sarah Cascone

The Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History is planning a timely new exhibition about the history of disease and how it has shaped our nation—and curators had it in the works well before the current pandemic.

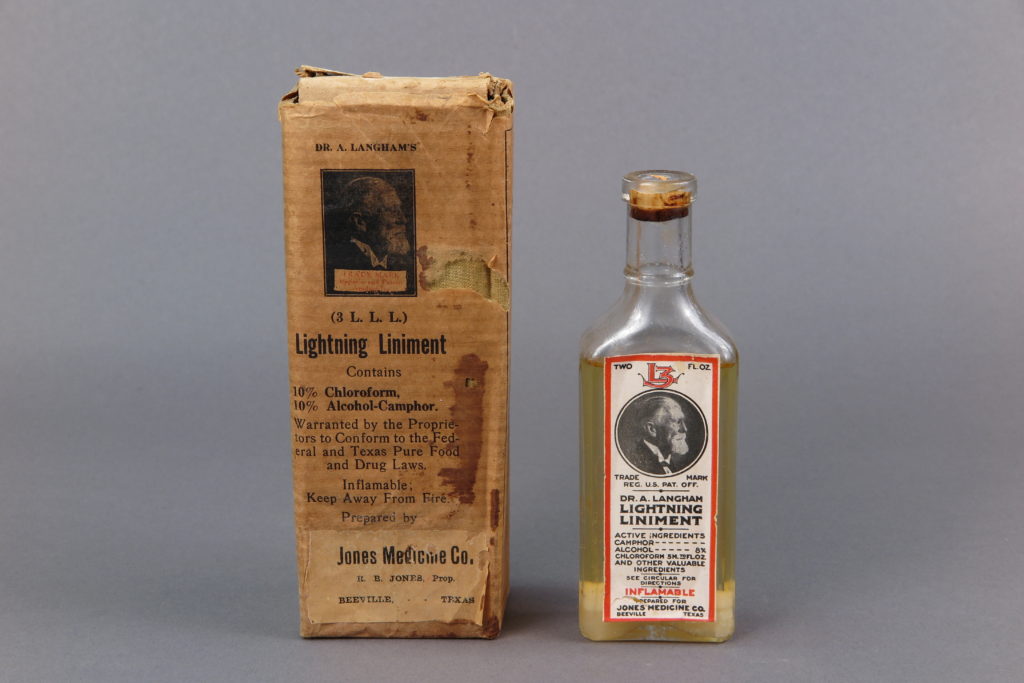

“We thought we would have to do a great deal of groundwork to help people understand,” Alexandra Lord, curator of the museums’s division of medicine and science, told Artnet News. “Now, when visitors walk into our exhibition and see quarantine signs, they will have a greater understanding of what quarantine means—not just the word, but the feeling of being cut off.”

Although no one at the museum expected anything to happen on the scale of the novel coronavirus, the curators were already designing the exhibition keeping in mind that it should be forward looking and address the ongoing effects of disease in the US today.

In planning the new longterm display, arranged chronologically, curators expected that the last section of the show would need to be continually updated. “We’re not that surprised, because disease has always played a major role in America history,” Lord said. “Pandemics have really shaped and changed who we are as a nation.”

From the earliest European contact with the continent, colonists brought diseases that ravaged the Native populations, who had no immunity to the foreign pathogens. And during the American Revolution, the British inoculated troops against smallpox, giving them a critical advantage against the colonists, until George Washington followed suit.

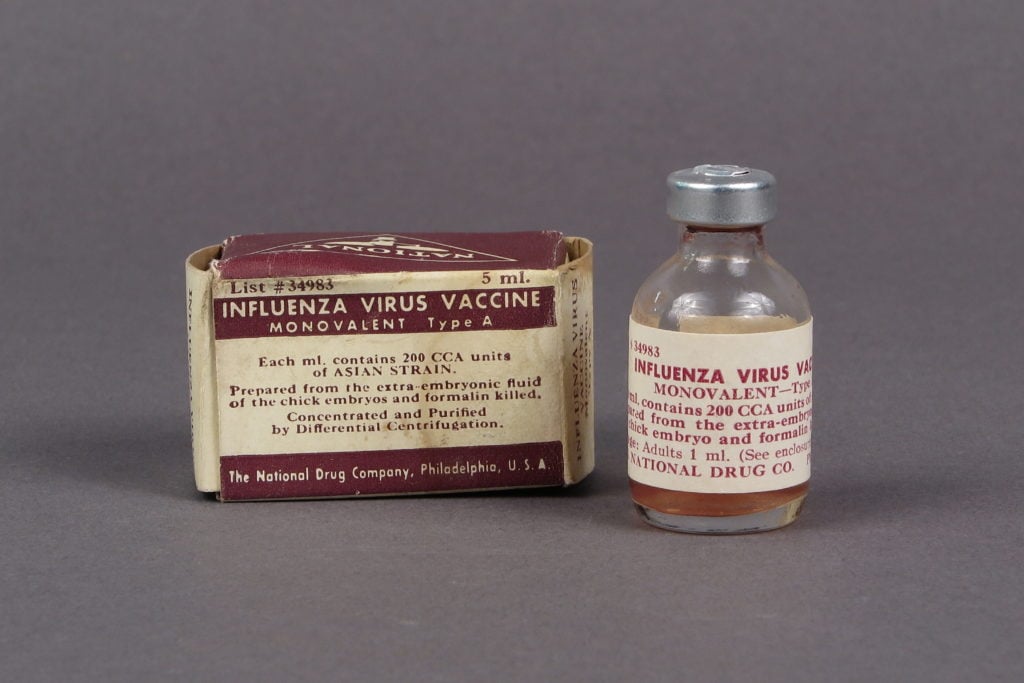

Vaccination objects from the Medicine Collections, including a smallpox vaccination shield (top left), wooden box of ivory points used for smallpox vaccination (center), and Codman & Shurleff Automatic Vaccinator (front right). Photo courtesy the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

The curators’ starting point is 1793, when the US was still a new nation. When yellow fever swept through the capital of Philadelphia, one in five people died. The wealthy fled in fear, including many of the city’s doctors, leaving members of the Free African Society to provide crucial medical care.

“For the people who lived through it, the epidemic was incomprehensible—it seemed to come out of nowhere,” said Lord. “It highlights a lot of things about American history and class structures. African Americans played a crucial role at a time that slavery was widespread and they were denied a voice. It sheds light on a lot of different stories.”

The 1837 smallpox epidemic again hit hard Native Americans in the Dakotas who had not yet been vaccinated by the government because they lived near few white settlers. “As a result, the smallpox just decimated the tribes,” said Lord. “That’s a story that really illustrates the impact that disease had on different communities in American history and also the ways in which the federal government did not take an equal approach to providing medicine and vaccination.”

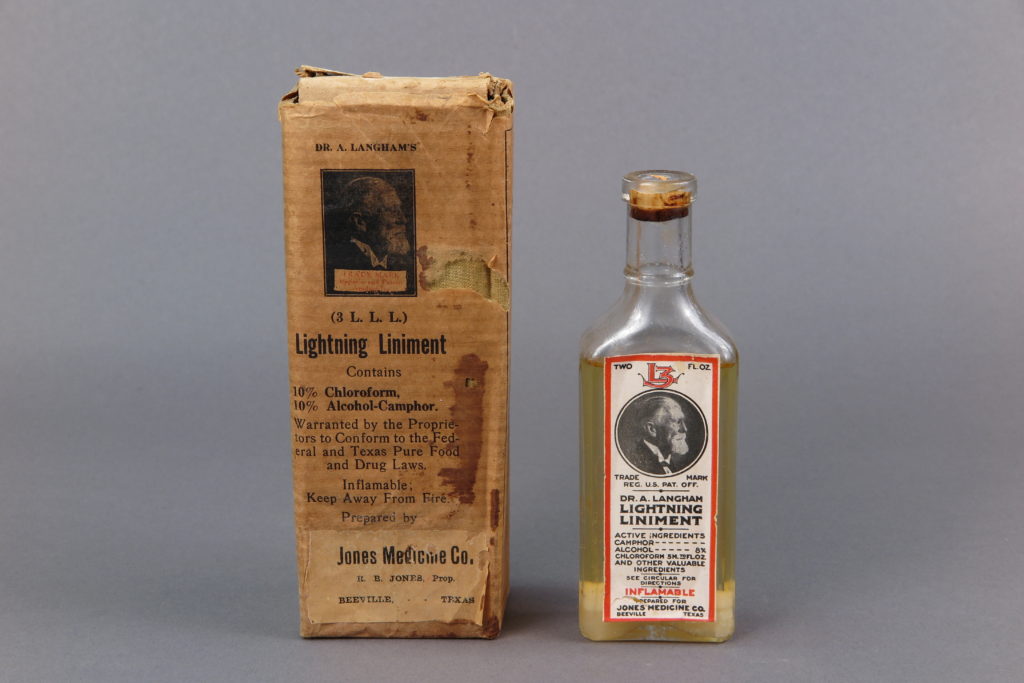

Photo courtesy the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

The third major disease outbreak featured is the cholera pandemic that struck California shortly after the Gold Rush brought a wave of settlers to the West Coast. “We always forget that when humans move, diseases move,” said Lord. Like the coronavirus today, the cholera pandemic of the 1850s “situates America—we’re not immune to global forces.”

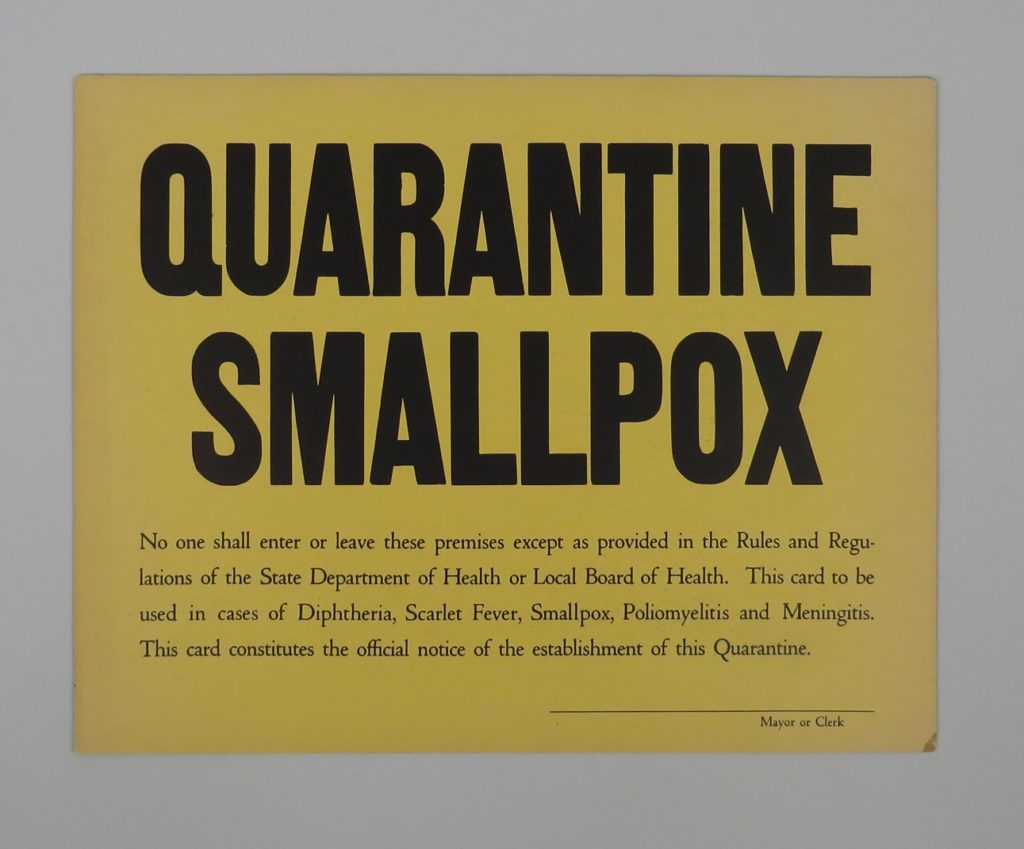

The show will highlight examples of success stories and of near-miss disasters, such as the eradication of smallpox in 1980—the only disease ever fully eliminated—or the quick medical response, in 1957, when a new strain of the flu threatened to spread across the globe.

“Flu pandemics occur when there’s an antigenic shift in the virus, and people who were exposed previously are no longer immune,” Lord said. “But in 1957, Maurice Hillemann, an American who had lost his parents in the 1918–19 Spanish flu, actually developed a vaccine very early on, rushed it into production, and really averted a major pandemic.”

The downside to defeating disease, however, is that serious illnesses like mumps and rubella may no longer look like a threat to later generations. “We will be talking about how many of these diseases have come back with lax vaccination,” said Lord.

Biological, influenza vaccine, Monovalent Type. Photo courtesy the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

“This is the curse of public health,” Lord said. “If public health manages to wipe out polio or smallpox, we tend to forget about it.”

Now, with coronavirus fresh in the public’s mind, the exhibition will hopefully reach audiences who are more receptive to learning about the ways in which disease has shaped our nation—and will continue to do so.

Lord added: “We feel it’s a very important story that Americans do not know.”