Art World

These 6 Fall Museum Shows Will Make You Rethink the Way You Look at the Natural World

This season, artists are offering myriad lenses for close observation of flora, fauna, and organic phenomena.

This season, artists are offering myriad lenses for close observation of flora, fauna, and organic phenomena.

Katie White

“Art is born of the observation and investigation of nature,” Cicero famously remarked. Rembrandt, meanwhile, called nature his only master. Both were nodding to a profound belief: that art is inextricably linked to its intimation of the organic world. History seems to agree: Across millennia and cultures, from Chinese scroll paintings to the Hudson River School, artists have sought to render nature’s myriad shapes, colors, and forms, but in new and distinctive ways.

Depictions of the natural world have taken on every style and significance imaginable; the breadth of its influence on art is so sweeping that it sometimes seems as pervasive as the air we breathe. Certain artists, however, have been so awestruck by a horizon line or flower petal or jungle canopy or raging sea as to make these the devoted focus of their practices. As summer eases into fall, we’ve decided to turn our attention to the beauty of the natural world, the only way we know how—through art. Here are six exhibitions on view across the United States this autumn that are deeply inspired by the majesty, and mayhem, of nature.

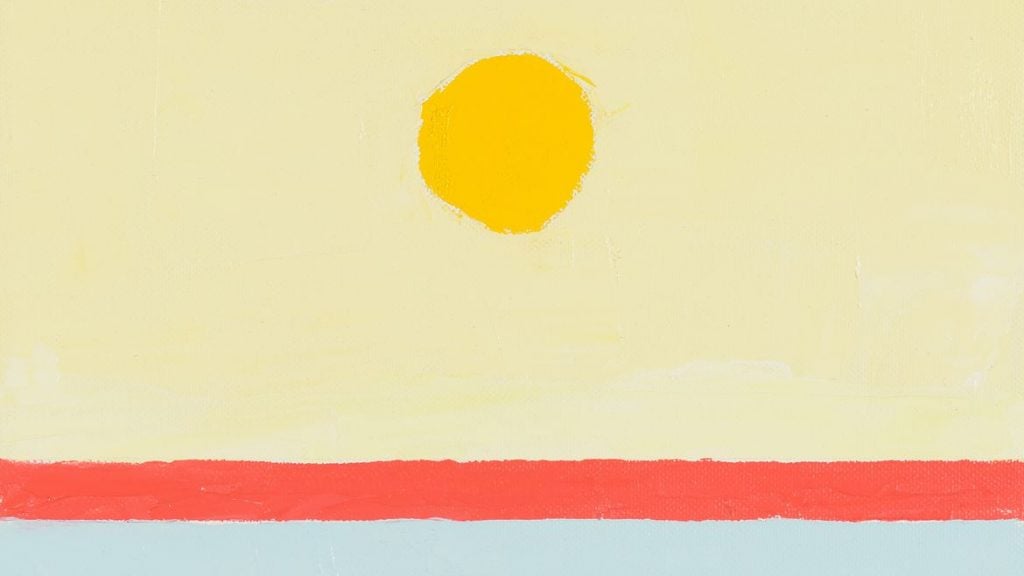

Etel Adnan, Untitled. Courtesy of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

Lebanon-born Etel Adnan’s creative and intellectual explorations have taken many forms in the course of her nearly century-long life. Born in Beirut in 1925 to a Greek mother and Syrian father, Adnan first earned acclaim as a poet and essayist, and, in 1978, published the defining novel Sitt Marie Rose, set amid the Lebanese Civil War. Adnan began to try her hand at painting in the 1950s while she was working as a professor in northern California. While Adnan’s writings of the era centered around critiques of war, her paintings turned instead to the beauty of the natural world. Adnan’s simple, geometric paintings are made while seated at her desk. Canvas laid flat, she applies pigment straight from the tube. In this survey show, one will find many renderings of Mount Tamalpais, which is visible from her longtime home in Sausalito, California. Seen here in shifting light and seasons, the mountain rises as—if not a shining, nevertheless soothing—beacon of hope.

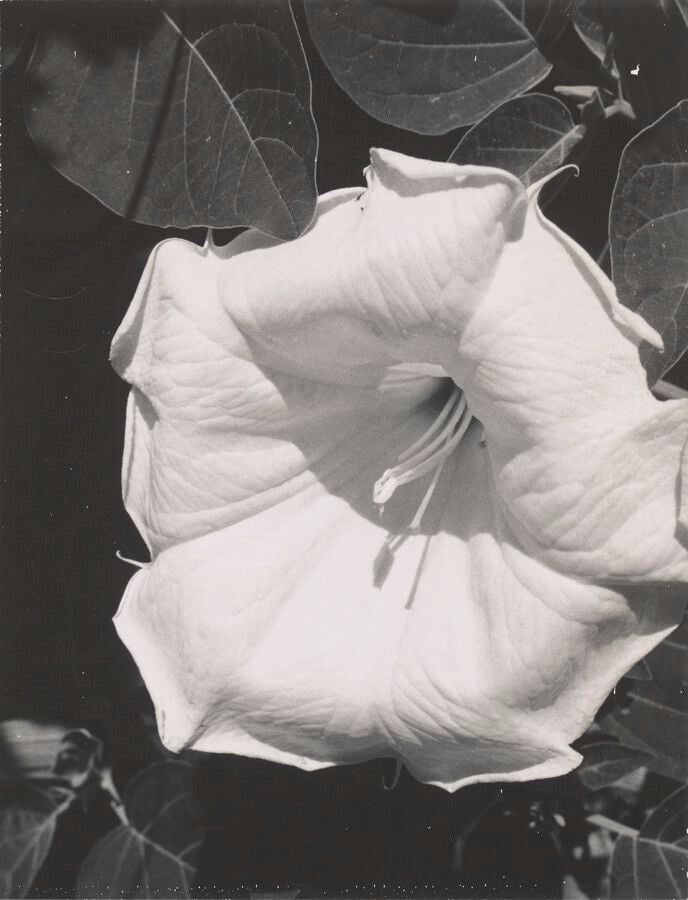

Georgia O’Keeffe, Jimsonweed (Datura stramonium) (1964–68). Courtesy of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe.

While Georgia O’Keeffe is famed for her brilliantly colored, close-up paintings of flowers, a lesser-known aspect of her practice was photography, which she explored with increasing frequency from the 1950s on. Married (somewhat infamously) to Alfred Stieglitz and a close friend of Paul Strand, O’Keeffe is familiar to art lovers as these photographers’ frequent model and subject. This exhibition, based on nearly 200 of her own photographs culled from a newly examined archive, offers insight into her own approach to the medium, with her beloved bones and flowers looking strangely new in black and white.

Clifford Ross, Hurricane II (2000). Courtesy of the artist.

For the past 30 years, American artist Clifford Ross has devoted his photographic and video practices to capturing the colossal power of the natural world. The first major museum exhibition of Ross’s oeuvre showcases the artist’s iterative exploration of the natural world across a range of media, often using specialized instruments to capture environmental phenomena. Ross’s imagery centers primarily on two subjects: a single mountain in Colorado and waves breaking along the coast of Long Island during a hurricane, and in one work, massive ocean waves thrash across equally imposing LED screens. The works are a meditative exercise in close looking at our surroundings.

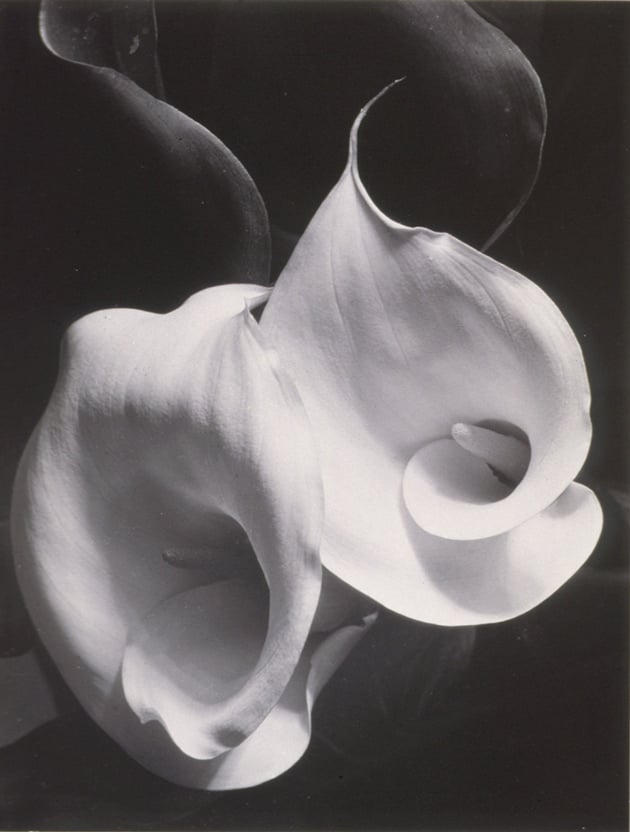

Imogen Cunningham, Two Callas (before 1929). Courtesy of the Seattle Art Museum.

In the early 20th century, Imogen Cunningham defined her own innovative style of photography with evocative black-and-white photographs of flowers, particularly calla lilies. Surprisingly, her seminal works haven’t received the major retrospective treatment in more than 35 years; this exhibition will bring together more than 200 original prints, many of her famed flower and plant studies, as well as portraits, street scenes, and her audaciously modern nude portraits (especially of women), for a comprehensive look at one of the most influential American photographers.

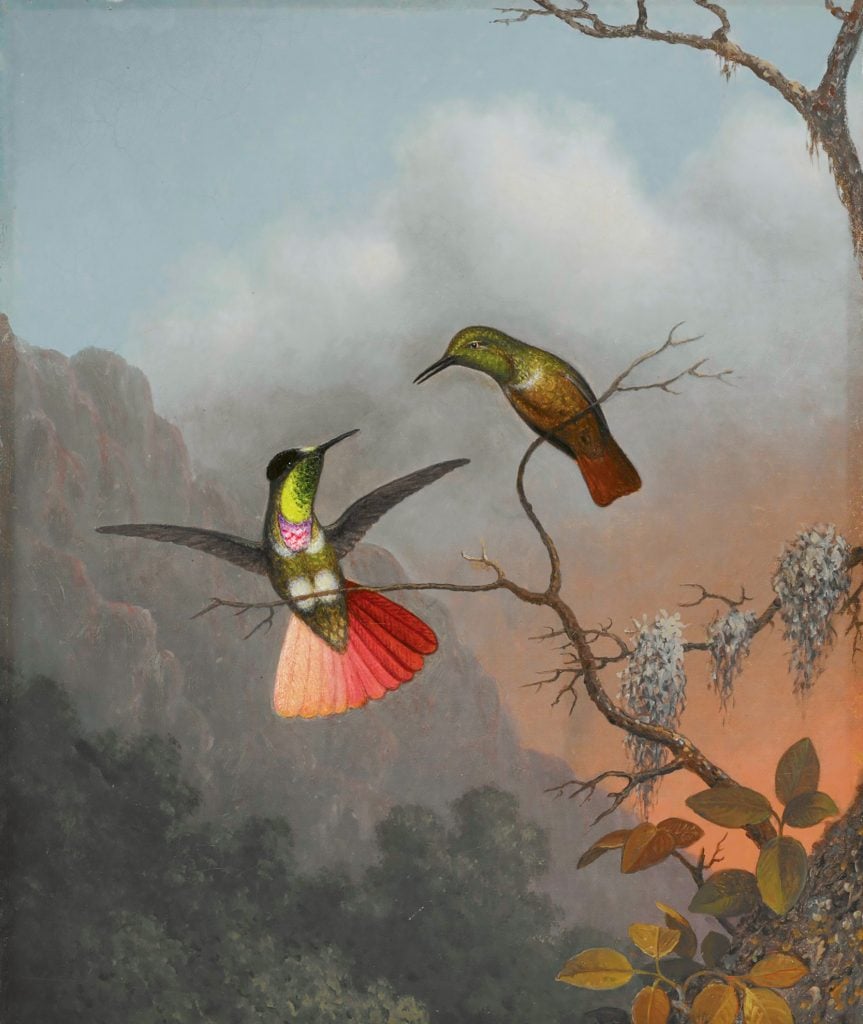

Martin Johnson Heade, Tropical Orchids (1870–74). Courtesy of Olana State Historic Site, New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation.

This multidisciplinary exhibition of nearly 80 works was inspired by “The Gems of Brazil” (1863–64), a series of influential paintings by Martin Johnson Heade, which depict dazzling hummingbirds the American landscape artist glimpsed while traveling in Brazil. The exhibition expands in several conceptual directions from there, with works that explore ideas of pollination, cultural and ecological exchange, and connections between art and science that have endured from the 19th century to the present.

Mimi Cherono Ng’ok, Untitled (2019). Courtesy of the artist.

Kenyan photographer Mimi Cherono Ng’ok’s practice is an ongoing exploration of how humans, botanical cultures, and various natural environments might learn to peaceably coexist. Working with an analog camera, the artist has spent the past decade traversing Africa, the Caribbean, and South America, capturing a diaristic archive of images that explore the roles of flora within these varied cultural settings. Her pictures are filled with latent and often intimate visual poetry, capturing vignettes of flowers in homes, on bedsheets, at night markets. Their significance deepens as one learns that some of the plants have been used as love potions or medicines, while others have taken root far from their source during histories of imperial expansion. The exhibition also marks the debut of the artist’s first film, which, through silent footage alone, reflects on the the transience of earthly life.