Archaeology & History

Spain’s Nerja Caves, an Underground Gallery of Prehistoric Art, Has Been a Tourist Destination for 41,000 Years, a New Study Says

Scientists have studied soot and charcoal residue left by prehistoric firelight.

Scientists have studied soot and charcoal residue left by prehistoric firelight.

Richard Whiddington

A new study from researchers at the University of Córdoba asserts that the Nerja Caves in Malaga, Spain, received more prehistoric visits than any other in Europe.

Since being unwittingly discovered by local children in 1959, the Nerja Caves, the walls of which are covered with Paleolithic art, have been a hotspot for tourists and archaeologists alike. The most recent research demonstrates the caves have been continuously visited for 41,000 years—or 10,000 years earlier than previously believed.

While considerable attention has been paid to the caves’ prehistoric art, which ranges from dots and lines to complex zoomorphic scenes, this latest research focuses solely on dating human activity. Prehistoric visitors relied on torch and firelight to illuminate the caves, leaving soot on the walls and charcoal on the ground for today’s researchers to collect and test using carbon dating techniques.

María Medina in the Navarro Cave (Malaga). Photo: University of Cordoba.

It’s a technique Marián Medina, the lead author of the article in Scientific Reports, calls “smoke archaeology,” and one she has practiced across Spanish and French caves.

“The paper includes 68 radiocarbon datings (48 of them unpublished),” the researchers explained in the article. “35,000 years of human occupation in the deep karst and at least 64 different phases have been identified, so far the largest number of visits known for a prehistoric cave in Europe.”

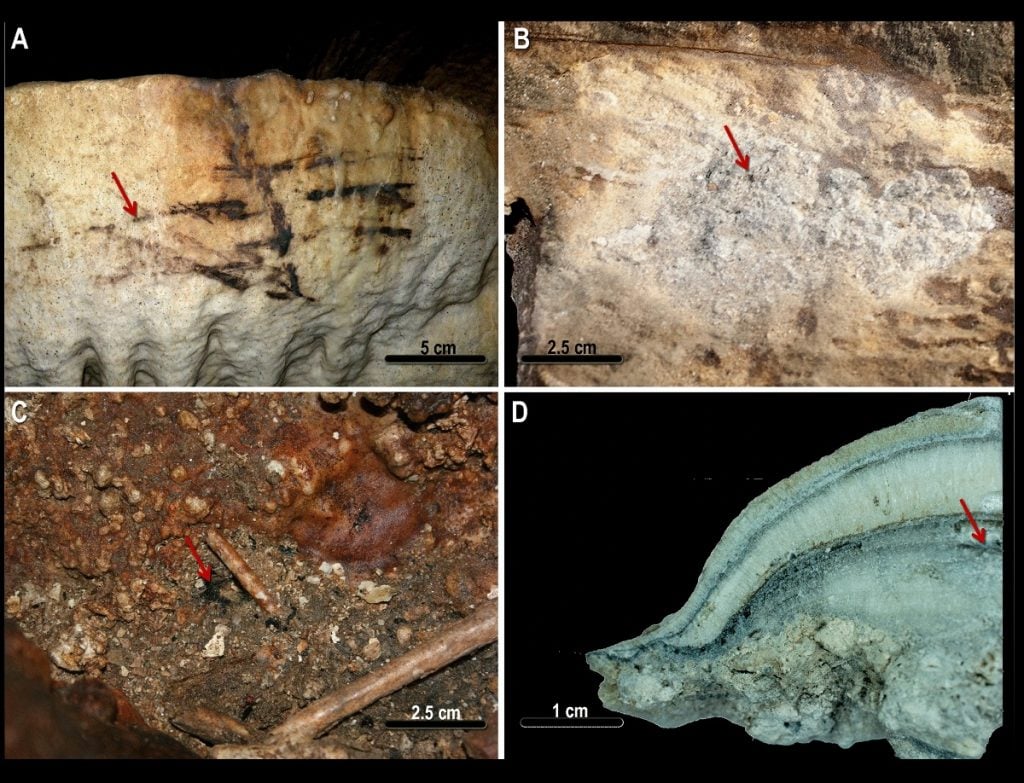

The residues the scientists studied include a black mark (A), micro-charcoal inside a fixed lamp (B), scattered charcoals (C), and a stalagmite section (D). Photo: Medina-Alcaide, M.Á., Vandevelde, S., Quiles, A. et al. “35,000 years of recurrent visits inside Nerja cave”, (Andalusia, Spain) based on charcoals and soot micro-layers analyses.

The oldest residues coincide with the Upper Paleolithic period of tool-making, known as the Aurignacian industry, one associated with early modern humans in Europe—though it’s also possible soot was the product of Neanderthal fires. Further research in the paper shows the enduring popularity of a particular type of pine for fires.

“The anthracological data from this study further reinforce this idea of a preferential and cross-cultural choice…for lighting activities inside caves during the Upper Paleolithic,” the article said.

For the lead author, investigations into the Nerja Caves can bring clarity on the evolution of human behavior. “There is still much it can reveal about what we were like,” she said.

More Trending Stories: