Art World

Is Nike the New Medici? Curator Neville Wakefield Says Brands Are Our 21st-Century Patrons

Kehinde Wiley and Ernesto Neto are among the artists signing up for corporate collaborations.

Kehinde Wiley and Ernesto Neto are among the artists signing up for corporate collaborations.

Rachel Corbett

It’s probably more lucrative today to be “a creative” than to work in most creative fields. As the middle range of the art market struggles to survive gallery closures and bifurcating prices, could corporate advertising be the solution for society’s most creative people—its artists—to make ends meet?

The curator Neville Wakefield seems to think so. “The de Medicis are not that different than Nike,” he recently told a crowd of young advertising professionals at the New York agency Chandelier Creative in a talk on how artists can provide new “disruptive” opportunities for brands.

Wakefield—along with artists Kehinde Wiley, Marco Brambilla, Robert Wilson, Freeman & Lowe, and Glenn Kaino—works with Creative Exchange Agency, a production and artist management company that pairs brands with art directors, illustrators, sound designers, social influencers, and, increasingly, visual artists. “There’s a danger of entering an air of impurity because there’s commercial patronage,” said Wakefield, who often produces fashion shows, product launches, and other events. But “the majority of artists I work with are excited to do it.”

One particularly successful example Wakefield gave was his 2012 collaboration with Brazilian artist Ernesto Neto and Nike, which had named Wakefield the “global curator” of its Flyknit sneaker launch. “They were interested in introducing the shoe as being about lightness, performance, sustainability, and really reinventing the idea of the running shoe, in terms of it being a soft architecture,” he said. He immediately thought of Neto, who’s known for his woven fabric structures that visitors can enter into and walk around. For the shoe’s debut in Rio de Janeiro, Neto built a 40-by-12-meter crocheted walkway that “communicated what the Flyknit shoe was about: adaptive architecture,” Wakefield said.

“Neto had never had a major Rio show, but this facilitated that. If done right, it can work for both parties,” he said. Nike later donated Neto’s work to the Brazilian museum Inhotim.

Ernesto Neto with his installation for Nike’s Flyknit shoes. © Nike Lab.

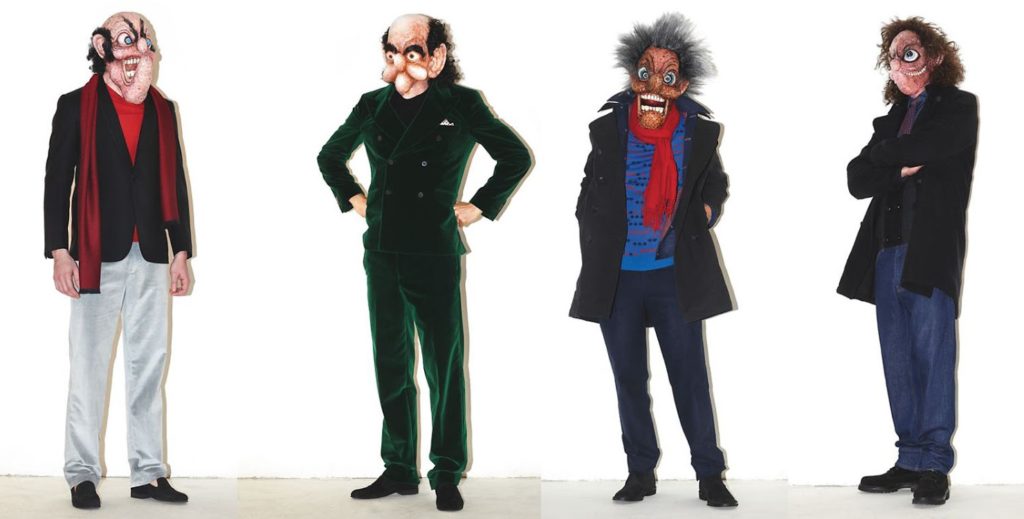

Similar projects include Robert Wilson’s video portraits of Nike-sponsored athletes; George Condo’s clown masks for the debut of Adam Kimmel’s 2010 menswear collection; Nick Cave and Vanessa Beecroft’s live performances for a Van Cleef & Arpels jewelry launch; and Kehinde Wiley’s patterns for the 2010 PUMA Africa collection.

“Artists have always been the sort of R and D [research and development] department for advertising agencies,” Wakefield said. “You go into agencies and what you see on the wall is artworks that then get transmogrified into advertising. What’s happening now is really fantastic, because it’s actually a much more direct conversation between the client and the artists. It doesn’t have to go through this extra layer of interpretation.”

Looks from Adam Kimmel’s Autumn/Winter 2010 collection, featuring masks by George Condo. Images © Adam Kimmel.

Artists are inherently amateurs in the advertising world, Wakefield added, which also makes them natural “disruptors.” “If they’re really going to do work that disrupts and changes up the perceptions of the world around us, they can’t become too good at what they do.”

“It’s really about finding new ways of disrupting preconceptions in order to get attention, which is what a lot of brands are after at the moment,” he said. “For brands brave enough to engage with that, it’s a big opportunity.”