Art World

‘This Whole World Is Ridiculous’: Collector Bert Kreuk’s New Book ‘Art Flipper’ Spills the Market’s Dirty Secrets

The author aims to lift the curtain on shady dealings in the art world.

The author aims to lift the curtain on shady dealings in the art world.

Brian Boucher

“The rules that govern the art world are made up,” says the rabble-rousing Dutch collector Bert Kreuk. He wants to demystify those rules in his new book, titled Art Flipper. The book—which recounts his involvement in one of the most talked-about art scandals in recent years, as well as his personal development as a collector—is out now in Dutch from the publisher Karakter. Widely covered in the Dutch press (but news to English-speakers), the book may also get US distribution, Kreuk says.

The memoir takes its name from the pejorative nickname Kreuk says artists and dealers attach to him and other collector-speculators. “I decided, if you call me an art flipper, let’s talk about labels,” he says. “It benefits people to label somebody as an art flipper. The art world has these so-called unwritten rules, but I started to recognize that those rules benefit only a few.”

After 20-some years as a collector, Kreuk broke a cardinal one of these unwritten rules. He organized a show of works from his collection at the Gemeentemuseum, in the Hague, and then put some of them up for auction. (It is generally considered good form to offer the work of a living artist back to the gallery from which it came, rather than put it up for auction, and bad form to sell a work that was recently loaned to a museum exhibition.)

After the Vietnamese-Dutch artist Danh Vō failed to deliver an allegedly agreed-upon work that Kreuk wanted to include in the Gemeentemuseum show, the collector sued the artist. The resulting two-year legal battle brought some of the art world’s gentleman’s agreements into the not-so-gentlemanly light of day.

Art-world skulduggery

In the book, Kreuk lays out other art-world skulduggery that he says has appalled him. A dealer once promised to sell him an artwork but then sold it to another buyer for a better price, he says. A bronze sculpture cast after an artist’s death was marketed as having been cast during his lifetime. A small set of dealers bid on artists’ works at auction, just to keep their prices high. And when collectors want works by hot artists, dealers extract concessions out of them, including getting them to buy works by gallery artists who are less in demand, thus “supporting the program.”

Kreuk and Vō settled their suit in 2015, but what emerges from talking to the collector is just how bright his contempt for the artist still burns. He remains sensitive about what he considers his shoddy treatment by parts of the art world, whose members, he believes, lined up dishonestly behind the artist. “The whole thing surprised me so much that I thought I should write about it,” he says.

Kreuk says his name was so besmirched by the Vō case that it scuttled his plans to loan a rare Sigmar Polke work to Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum. Talks with the institution were underway for some time, he maintains, but when Beatrix Ruf took over as director, she told him that she couldn’t accept the loan—though she would accept the painting as a donation.

“So you don’t want to be associated with Bert Kreuk because he’s labeled an art flipper, but it’s okay when I donate something? This whole world is ridiculous. It’s crazy,” Kreuk says.

(Asked to comment on Kreuk’s account, the museum sent a statement describing a pleasant conversation about the possibility of a Polke loan, but noting that “neither Beatrix Ruf nor two other staff members of the museum who were present in the meeting recognize the statement that a donation has been suggested from our side. Apart from this, we can only state that it is our policy that the contents of our conversations with collectors are treated with confidentiality and that they are not shared with others.”)

“It’s about the system”

Despite these juicy episodes, the book is not quite a tell-all. “I don’t want to mention names,” Kreuk says (though the Stedelijk seems to be an exception to this rule). “For me, it’s irrelevant, because it doesn’t serve any purpose. People will recognize themselves. But it’s more about the system and the mechanism.”

In the memoir, Kreuk also traces his family history and recounts how and why he became a collector in the first place. The book details his rough childhood under a violent father, which he escaped by moving with an uncle to America. He started out penniless and built up a successful business serving the airline industry. The same uncle opened his eyes to art with museum visits. He became interested the Romantics, then the Impressionists, and finally developed a passion for contemporary art.

Bert Kreuk’s new book may soon get US distribution.

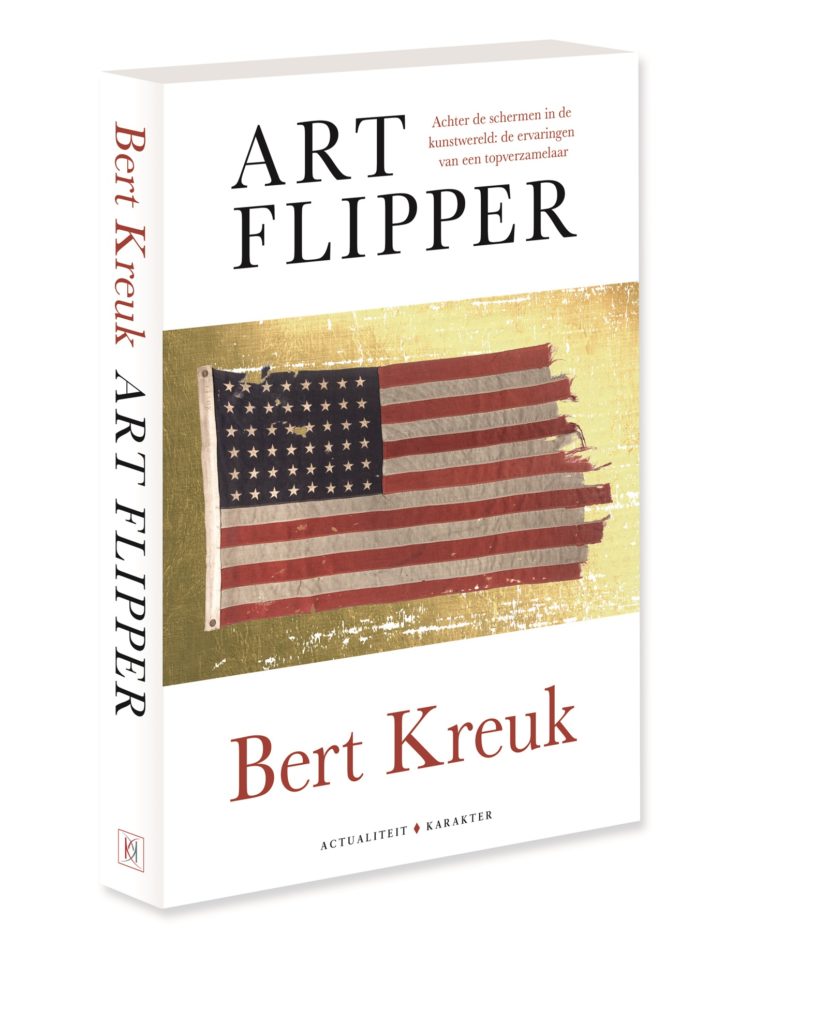

One of Kreuk’s most meaningful acquisitions is on the book’s cover. In 2016, Kreuk bought the flag that was flown on US Navy vessel LCC 60, which stormed the beaches of Europe on D-Day, for some $514,000 at Heritage Auctions. His family owed the servicemen on those boats a great debt, he says, since he lost relatives in Nazi bombing raids on Rotterdam in 1940. On the cover, that US flag, pierced by a German bullet, is set against a background of peeling gold leaf—one of Vō’s signature materials.

To Kreuk, the peeling gold symbolizes not only his fateful run-in with the artist but also his disillusionment with the art world more generally. (The design contrasts the cravenness of some in the art world with the American soldiers’ courage, he suggests.) After the Vō case ended, “the shine was off, and it took a while before the joy of collecting came back,” he says.

Kreuk plans to donate any profits from the book to youth projects in the Netherlands. “I don’t want to make any money out of it,” he says. “In my uncle, I had someone who lifted me up and encouraged me to get the best out of myself. That’s what I want for these kids.”