Art World

New Documentary Unravels the Mystery of Vivian Maier, Photographer (and Nanny)

The reclusive artist is being hailed as a genius in death, but how did she live?

The reclusive artist is being hailed as a genius in death, but how did she live?

Benjamin Sutton

“I’m sort of a spy,” Vivian Maier once told a man who asked her what she did. Maier died in poverty and obscurity in 2009 after working as a nanny most of her life, but, in a way, she was also a spy. A self-trained and prolific street photographer, Maier shot thousands of rolls of film over five decades, all of which might have been lost if John Maloof hadn’t bought a box containing hundreds of them at a storage auction in 2007 for $380. His struggle to piece together her life and oeuvre, and to retroactively write her into the photography canon, is the subject of Finding Vivian Maier, a new documentary he co-directed with Charlie Siskel.

However, like any good spy, Maier made it difficult for anyone to dig up her past. She was staunchly secretive and, as she grew increasingly more mentally unstable later in life, incredibly paranoid. She asked the families who took her on as a nanny to install extra locks on her door and forbade anyone from going into her section of the various houses in which she lived. When pressed for her name she provided alternate spellings and outright pseudonyms; “V. Smith” was a go-to. She occasionally affected a French accent, though she was a native New Yorker and lived in Chicago most of her life—her mother was French. Maloof pieces together these and other details from the belongings of Maier’s he acquired, clues in her photographs, and interviews with the parents for whom she worked, as well as their now-adult children.

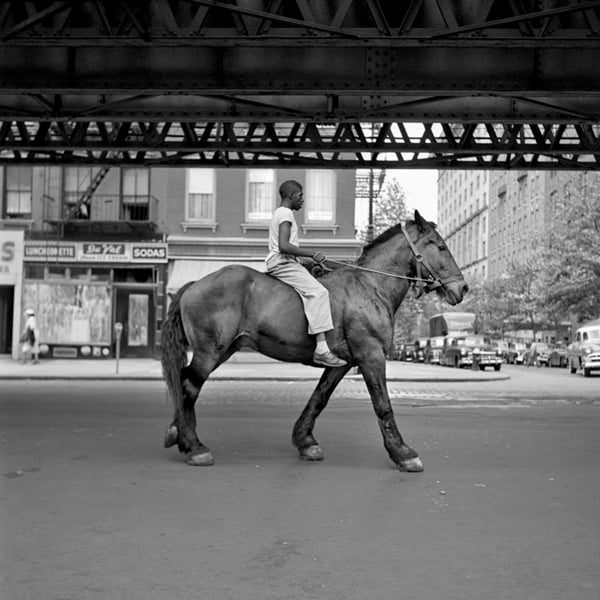

African-American Man on Horse NYC from John Maloof and Charlie Siskel’s Finding Vivian Maier.

Photo: Vivian Maier. Courtesy of the Maloof Collection.

The search documented in Finding Vivian Maier is two-fold, combining Maloof’s quests to fill out the photographer’s biography and to gain the art world’s acceptance of her work. The latter is less interesting because the work is so overwhelmingly strong that it’s clearly just a matter of time. Early montages of Maier’s black-and-white and color photographs of playful, heartbreaking, mysterious, and ominous street scenes leave no doubt regarding her incredible talent. Just to be sure, though, heavyweight photographers Joel Meyerowitz and Mary Ellen Mark rhapsodize about her work. “She had a sense of humor, and a sense of tragedy,” Mark observes. “She had it all.” In the course of the film, prominent photography dealer Howard Greenberg signs on to represent Maier’s estate. The first few shows of her work are hugely successful. At one point Maloof indignantly reads a rejection letter from MoMA, but her work will undoubtedly hang in the 53rd Street building before the decade is over.

The investigation into Maier’s personal life is infinitely more engaging, and thankfully makes up the bulk of the documentary. It takes us from an improbable interview with former television talk show host Phil Donahue—who employed Maier briefly—and an abandoned mansion in the Hamptons where Maier worked in the 1950s, to New York City’s hall of records and the tiny French village where her mother was born. Though she initially comes across as a quirky and reserved woman who marched around Midwestern cities taking photos with her employers’ kids in tow—“They used to call her ‘army boots,’” a longtime friend and former employer recalls—the psychological portrait Maloof creates becomes darker as Maier gets older. Children who had her as a nanny later report instances of abuse, her hoarding habits become more extreme, as do her outbursts, and the number of employers willing to put up with her unusual behavior starts to dwindle. Accounts of her abusive behavior are accompanied by speculation about her own trauma. This biographical investigation is incredibly engrossing, and Maloof and Siskel give each interview subject ample time to develop and reveal the contradictions of their respective relationship to Maier.

Man being dragged by cops at night from John Maloof and Charlie Siskel’s Finding Vivian Maier.

Photo: Vivian Maier. Courtesy of the Maloof Collection.

Fortunately the directors have organized Finding Vivian Maier according to their gradual unmasking of this mysterious character. The places where that process diverges from the chronology of her life are its few major missteps. A strange aside about a Hamptonite’s friendship with her maid seems to oversimplify the type of intimate employee-employer relationship that is on of the film’s main subjects. A passage about Maloof’s reluctance to make such a private person’s life so public—“I feel a little guilty about exposing the work of someone who didn’t want her work exposed,” he tells the camera—comes off as half-hearted. A closing montage of recent jam-packed gallery shows comes off like an advertisement. But Maier’s story is so interesting, her life so sad, and her photographs so startlingly good that these flaws barely register as the film’s 83 minutes zip along.

In addition to the photographer’s troubled life and brilliant eye, Finding Vivian Maier draws out the telling similarities between Maier and Maloof. Both come off as hoarders, to varying degrees, with irrepressible obsessive tendencies. In one especially illustrative scene, Maloof follows Maier’s cryptic reconstruction of a slain babysitter’s final hours. Both come across as incredibly curious. And each is more than willing to indulge their curiosity and stubbornly follow wherever it may lead. For Maloof it has paid off, figuratively and literally, as editions, exhibitions, and books of Maier’s photographs continue to come fast and furious—the next, the massive tome Vivian Maier: A Life Through the Lens, is due out in October from Harper Design.

For Maier, though, things end on a much sadder and more ambiguous note. She was a gifted photographer whose secretive and suspicious behavior prevented her from gaining recognition during her lifetime. But, as several interviewees postulate, it’s unclear how she might have handled widespread recognition and scrutiny of her work. “She didn’t have the measures of success that people aspire to,” one woman who had her as a nanny concedes, “but she didn’t have to compromise one bit.”

Finding Vivian Maier opens at select theaters in Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York on March 28.

Woman at the NY Public Library from John Maloof and Charlie Siskel’s Finding Vivian Maier.

Photo: Vivian Maier. Courtesy of the Maloof Collection.