Last year, roughly 20 curators and historians from Smithsonian museums quietly convened to consider the Institution’s stance on restitution—acting to address a question confronting many cultural institutions as they reckon with the colonial histories that shaped their collections.

What that team, called the Ethical Returns Working Group, came up with after a six-month review was shared with Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie Bunch. “This is an important time not only for the institution but also the museum profession,” Sabrina Sholts, a curator at the National Museum of Natural History and a member of the Working Group, told Artnet News earlier this year.

Now, the Smithsonian has announced that it has implemented those recommendations as institutional policy, effective as of last Friday, April 29. Moving forward, museum objects found to have been looted, taken under duress, or otherwise unethically sourced will be reviewed against a new set of criteria—and, in many cases, fast-tracked for return to their country of origin.

That represents a notable departure from the Institution’s previous policy, which provided that its museums needn’t return artifacts that were obtained legally. Now, for the Smithsonian, questions of return have more to do with morals than laws.

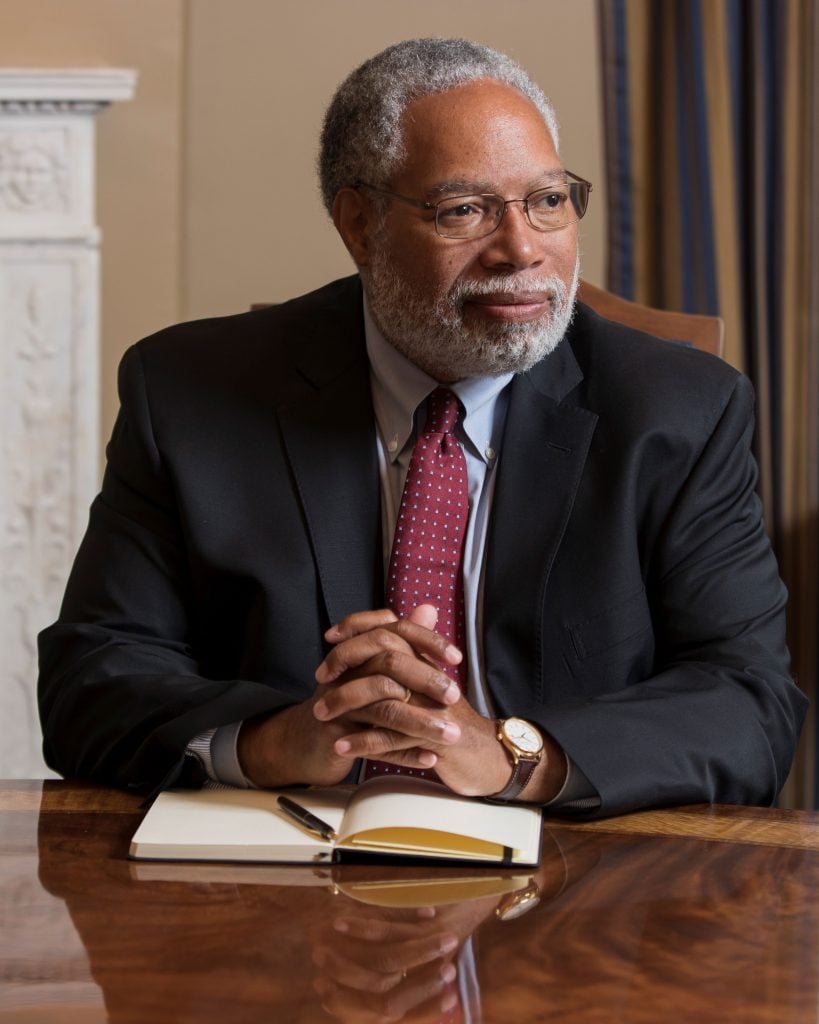

Lonnie G. Bunch III, the 14th Secretary of the Smithsonian. Photo: Robert Stewart / Smithsonian Institution.

“There is a growing understanding at the Smithsonian and in the world of museums generally that our possession of these collections carries with it certain ethical obligations to the places and people where the collections originated,” Bunch said in a statement. “Among these obligations is to consider, using our contemporary moral norms, what should be in our collections and what should not.”

“This new policy on ethical returns,” he added, “is an expression of our commitment to meet these obligations.”

The anticipated policy did not arrive in the form of bulleted, across-the-board rules for restitution. Instead, it comprises a set of institutional values by which returns will be measured. Most significantly, it explains that individual Smithsonian museums will each establish “procedures for deaccessioning and returning collections” based on “ethical considerations.”

Previously, restituting an object from the collection necessitated a long, bureaucratic process that required approval by the Institution’s Board of Regents. Now, more authority has been granted to museums. Only in cases when an object is “of significant monetary value, research or historical value, or when the deaccession might create significant public interest,” will the board now weigh in.

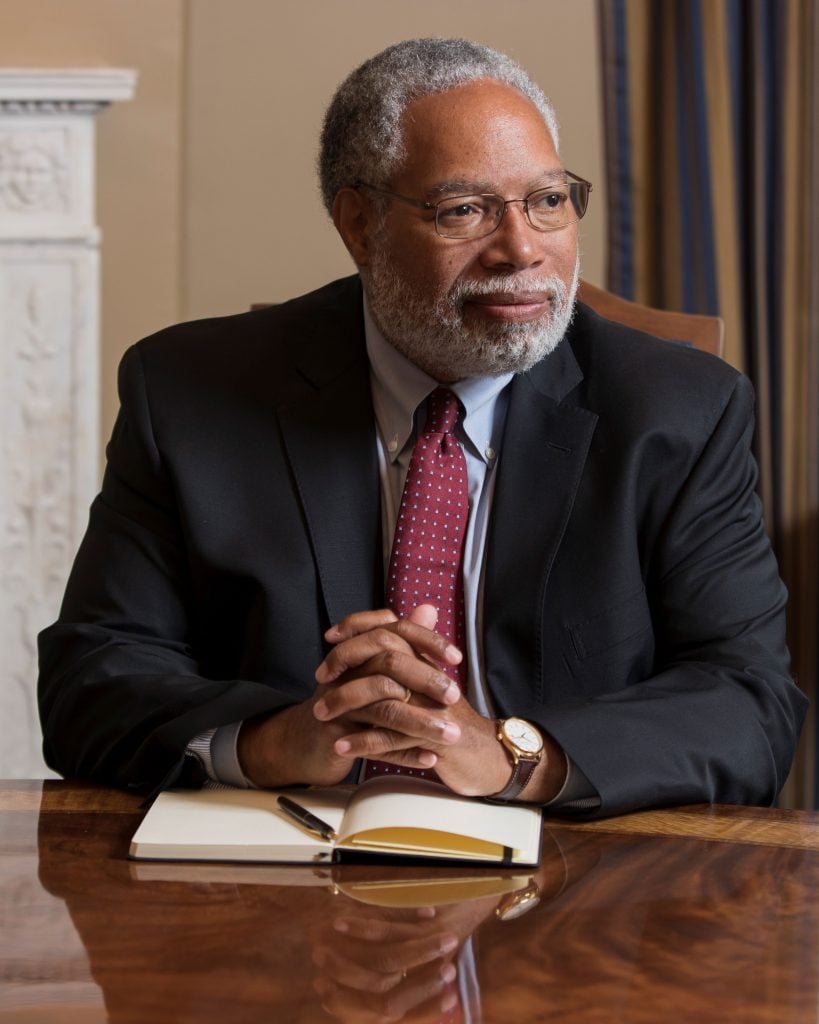

A Benin plaque from the mid-16th to 17th centuries. Courtesy of the National Museum of African Art.

The formalized policy comes on the heels of the Smithsonian’s announcement that it will return “most” of its 39 Benin Bronzes, all held in the collection of the National Museum of African Art, to their homeland of Nigeria. Other objects that may be subject to deaccessioning include stolen art or human remains removed without consent.

But the Smithsonian was clear that the new policy does not mean that its researchers will reassess each of the 155 million objects in its collection. Rather, it will review items as questions arise from communities, scholars, or in the process of preparing for an exhibition.

“We affirm the Smithsonian’s commitment to implement policies that respond in a transparent and timely manner to requests for return or shared stewardship,” the Ethical Returns Working Group said in a “Values and Principles Statement” released alongside the Smithsonian’s new policy. “We will galvanize a Smithsonian community of practice that respects and actively engages with various perspectives and affirms our commitment to a shared future regarding the ongoing stewardship of Smithsonian collections, as well as the opportunities to address the ethical return of human remains and objects of cultural heritage in the Smithsonian’s care.”