Reviews

How Egon Schiele Went From Radical Punk to Respected Artist

Vienna exhibition reveals a new side to the provocative painter, in time for his centenary.

Vienna exhibition reveals a new side to the provocative painter, in time for his centenary.

Sarah Hyde

In conservative, polite Vienna, in the year before the 100th anniversary of Egon Schiele’s death, the enthusiasm and genuine affection for this artist is at an all-time high. A new exhibition dedicated to his work opened at the Albertina Museum last week, casting a new light on the artist’s legacy.

The Schiele we think we know is the cover boy of teenage angst; an archetype of punk, with spiky black hair crowning a skinny frame. He loved reading Rimbaud just like Patti Smith, and idolized the Apache, an anarchic Parisian street gang that he had read about in a magazine.

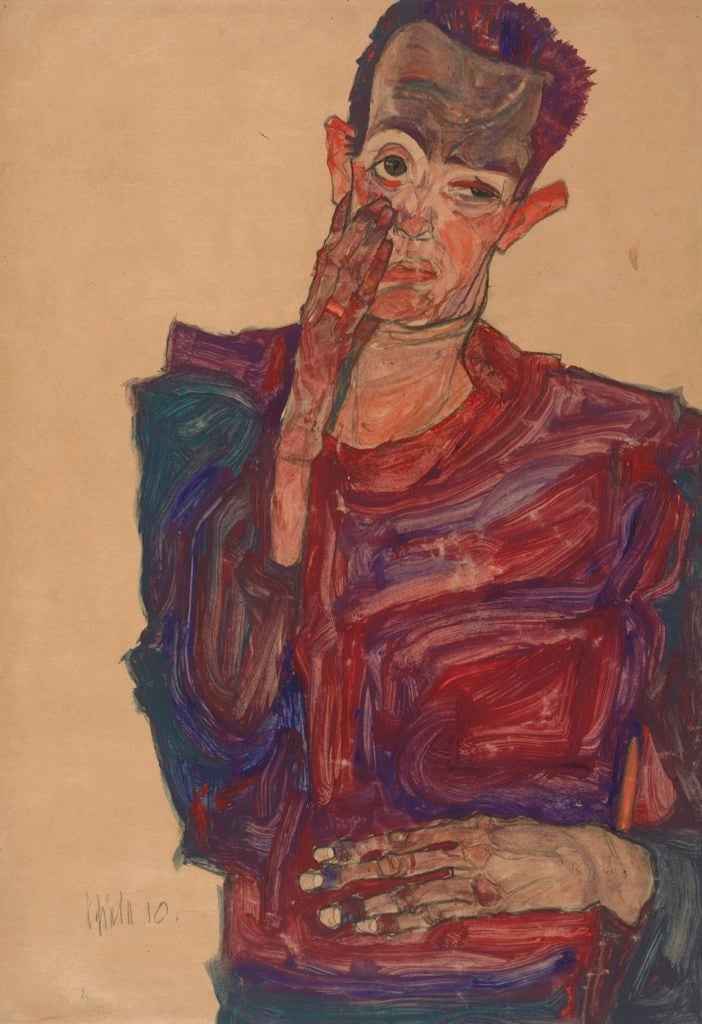

Schiele didn’t care about convention—flouncing out of art school he wanted to live and work differently. He created a new aesthetic of emaciated isolated ugliness, and lived for love and art. Famously, he even got arrested for obscenity. This Schiele confronts us in angry nude self-portraits, scrutinizing his form with dramatic self-loathing, contorting himself into tense uncomfortable postures that express his inner angst.

However, by the time of his unfortunate death in 1918, Schiele had triumphed, made a sensible marriage, headlined the 49th Secessionist Exhibition in 1918, where he sold five pictures and received many commissions. He was no longer the poster boy of punk—he was the city’s leading artist.

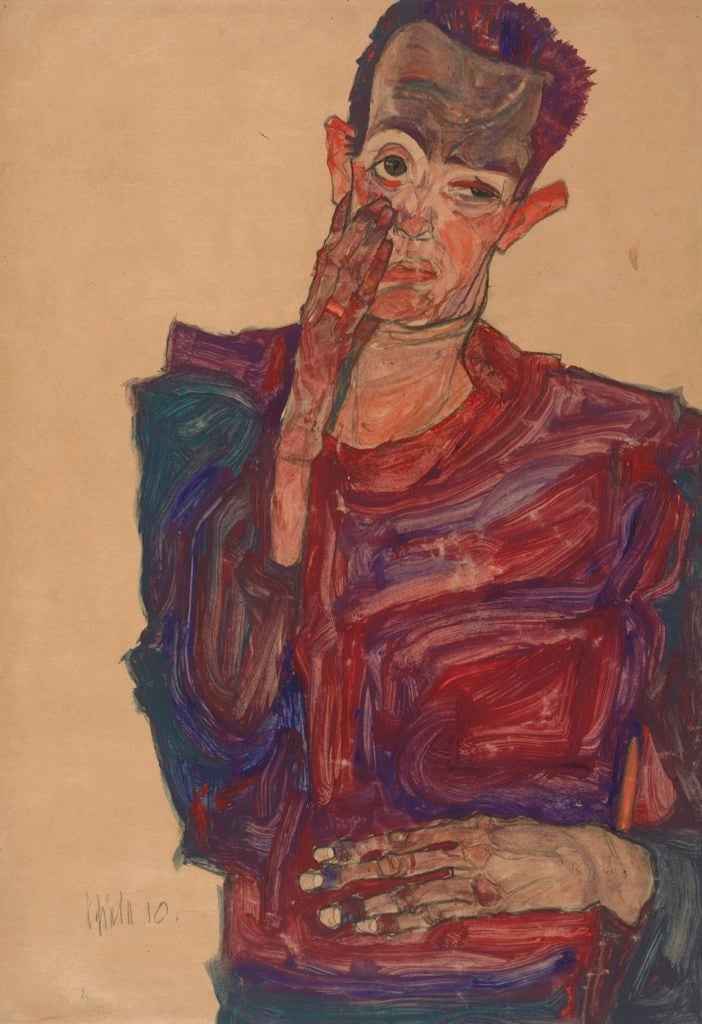

Egon Schiele, Self-Portrait in Yellow Vest, (1914) ©Albertina, Vienna.

The new exhibition “Egon Schiele” provides an opportunity to challenge our preconception, discover the difference between his public and private work, and appreciate how ultimately successful this beloved enfant terrible had become. The Albertina houses the world’s largest collection of works on paper by Schiele, a collection that began in 1920, just two years after the artist’s death.

With 20 additional loans from other institutions, this show has been curated by Klaus Albrecht Schröder and features 160 works, thematically displayed across nine rooms, with blown-up photographs. Many of the works will be out on loan in 2018, which looks to be a bumper year for Schiele fans.

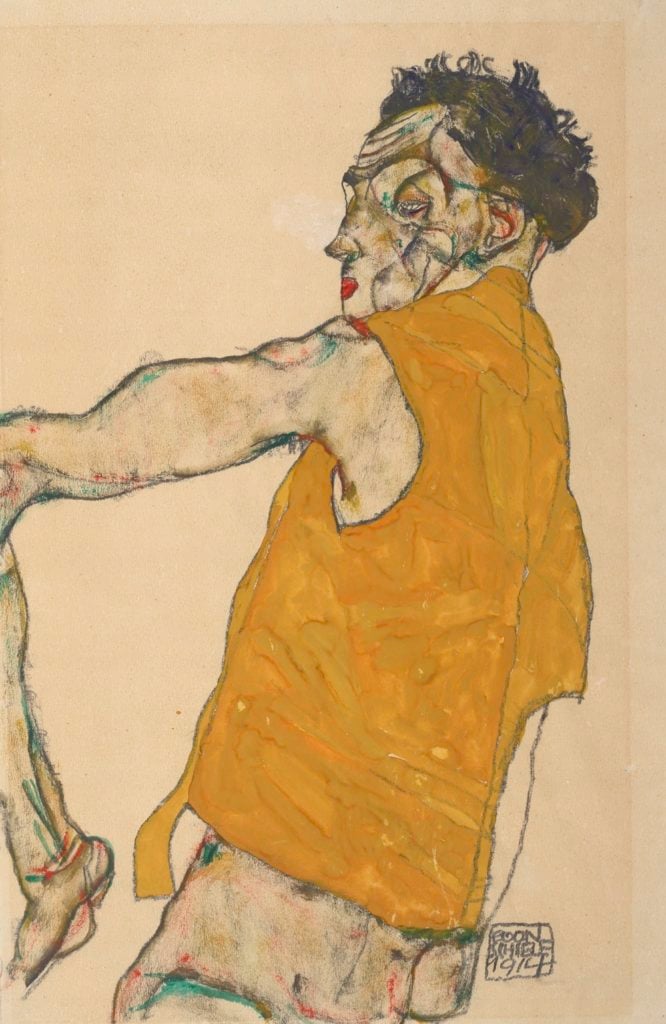

Egon Schiele. Portrait of the Artist’s Sister-in-Law, Adele Harms, (1917). ©Albertina, Vienna.

The exhibition opens with some fascinating early drawings, before the artist became the Schiele we know: A self-portrait from 1906 is almost romantic in appearance, and clearly produced by a competent draftsman. While these works are pleasing, they’re quite unremarkable; only a real connoisseur would be able to attribute them to the artist. Liegender Frauenakt (Reclining nude) (1908) is neatly drawn—perhaps the simplicity of line is a clue to his later work—but it is not until 1909 that Schiele’s distinctive style emerges, breaking radically with traditional values. A year later, in 1910, some of his great early works are produced.

Weiblicher Akt (Female Nude) (1910), although a little atypical, is particularly good, exemplifying the challenges that Schiele so enjoyed creating. It is also very beautiful. A pencil drawing of a young nude girl—she is no older than 13—depicts her sucking her finger, her eyes meeting the viewer’s gaze knowingly. Can a drawing so self-aware be described as innocently beautiful? What’s certain is that it is pure provocation.

Another remarkable work from 1910 is The Artist with a Model. The only known drawing in which Schiele represented himself at work, it gives important insight into the artist’s working practice. The model stands perhaps less than a meter in front of him; she would be able to feel his breath, if she weren’t so lost in her own world, gazing in the mirror, arranging her body in a fine new hat.

Another arresting picture from 1910 is Girl taking off her shirt, which is one of the few works which achieves any kind of sexual modesty and anticipation.

When looking at Schiele nudes—and like it or not, erotic nudes are the majority of his oeuvre—it is important to know how close the artist was to his models. Schiele executed his sketches at lightning speed, once he had coaxed the right pose from his sitter. The drawings were executed in a maximum of two or three minutes.

Not all the pictures in the exhibition are sketches and the portraits of men show a much more formal side to the artist. As art historians are quick to point out, there is nothing sexual in his portrayal of boys and men. In 1910 Schiele produced a fabulous portrait of fellow artist Max Oppenheimer. His own self-portrait of 1911 with a peacock waistcoat reveals Schiele’s public persona. His eyes meet the viewer with an almost conspiratorial look and his hands form the curious V gesture which appears like a sign in many of his works. In this portrait our angst-ridden soulmate is composed, elegant and even peppy, represented with a halo. There is a duality between public and private which runs throughout his oeuvre. The erotic nudes may be exhibitionist, but their context is private and it is certain that they were not for public exhibition during Schiele’s day.

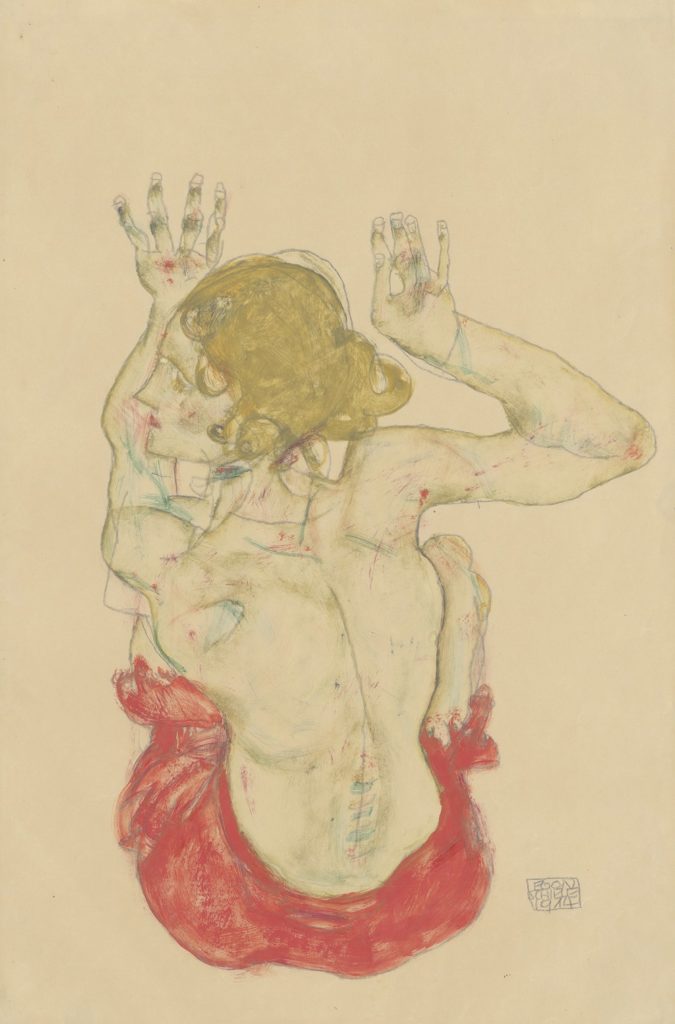

Egon Schiele, Seated Female Nude, Back View, with Red Skirt, (1914) Courtesy Albertina, Vienna.

Schiele was a prodigious artist, leaving over 330 paintings and 2,500 drawings from a career that spanned barely 10 years and inevitably, given the powerful erotic nature, much has been made of why Schiele produced so many nudes. It may well have been a simple matter of economics: According to coeval source Heinrich Benesch, Schiele was charming, elegant, with a natural nobility of spirit, and significantly hopeless with money. Living hand to mouth, he would sell his works painted on wrapping paper for between 10 and 30 crowns where he could. He liked to spend every penny he had as soon as he got it and his stocking bill alone must have been considerable. Perhaps his choice of subject matter was as simple. As Oskar Kokoschka stated, pornography always flourished in Vienna, although it was forbidden. The more pornographic the easier to sell.

By 1912, things got a little bit out of control in the 20-year-old artist’s studio where he was living with his mentor, Gustav Klimt’s model, Walburga Neuzil, in a small town on the fringes of the Vienna woods. In April, Schiele was arrested under the suspicion of abduction and statutory rape of a minor. Both charges were dropped and in all he was imprisoned for only 20 days. The final three were his sentence for failing to keep his erotic drawings in a sufficiently safe place and exposing them to the children that came to model at his studio. 125 drawings were seized and destroyed by the police.

The Albertina exhibition provides a much broader range of works than the hugely successful “Radical Nude” presented at London’s Courtauld in 2014, allowing the viewer to pick up on the stylized motifs that identify Schiele’s work. The isolation of the subjects from the spatial and temporal context is perhaps, in retrospect, one of his greatest ideas, as the works without background appear to be eternally modern and fresh.

Egon Schiele, Sunflowers, (1911) Courtesy Albertina, Vienna.

Without question Schiele’s greatest achievement is his line. It defines the work conveying both form and emotional energy at a level that has not been surpassed. Then there is the twisting of the figure, not quite contrapposto, it is much less elegant and folded, always uncomfortable and awkward. His rangy attenuated forms were anything but beautiful or even anatomically correct, and his subjects are often positioned at awkward angles.

During different phases the use of color, highlight, shading or shadow change but the line remains and, remarkably, even his flower pictures are immediately recognizable as Schiele. His twisted, disheveled “sunflowers” could be produced by no one else.

“Egon Schiele” is on view at the Albertina Museum, Vienna from February 22 to June 18, 2017