Art World

Five Unforgettable New York Art Moments of the Last Five Decades

Here are the events that cemented New York’s status as the global capital of art over the last 50 years.

Here are the events that cemented New York’s status as the global capital of art over the last 50 years.

Artnet News

It’s not hard to get romantic about New York’s place in art history. Just picture Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Robert Motherwell holding court at the Cedar Tavern in the 1950s, or all the characters that floated through Warhol’s Factory in the 1960s. This is an artist’s city, and those that make it through its gauntlet are often rewarded with a share of its mythology.

New York remains the global capital of art today, but the more recent events on which it hangs this crown aren’t so set in stone. What is, say, the definitive New York exhibition of the 1980s? What artwork encapsulated the feeling of living in the city in the 2000s? What will we remember from the last 10 years?

In an attempt to answer some of these monumental (and monumentally subjective) questions, we curated a list of several New York art “moments” of the last five decades we felt were the most enduring. Take a look.

Gordon Matta-Clark, Day’s End (Pier 52) (Exterior with Ice), 1975, created by slicing holes in the exterior of a shed on Manhattan’s Pier 52. Photo courtesy of the Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The downtown art scene of 1970s New York is remembered fondly by almost everyone except those that actually experienced it. Back then, Manhattan was oriented uptown, and the borough’s cutting edge creatives were making their way to the derelict industrial neighborhoods of the south. Life was dirty and dangerous down there, though, and even if the lofts were big and cheap, they weren’t always pretty.

Further down this list you’ll find public artworks that amounted to big, costly civic efforts. Gordon Matta-Clark’s landmark artwork Days End (1975) was the exact opposite. Without a permit, the artist cut a giant aperture in the side of an abandoned building overlooking the Hudson River—and he did it himself. It was risky, crude, and beautiful, just like the version of ’70s New York so often sentimalized today. Sadly, the Days End structure was demolished just a few years later—the first step in turning the West Village waterline into the redeveloped hub it is today.

David Hammons, Day’s End (2021) at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Photo by Eileen Kinsella.

The staying power of Matta-Clark’s rogue installation is evident in the work of another seminal New York artist. In 2021, David Hammons’s homage, also called Day’s End, debuted at the Whitney Museum of American Art. A public artwork seven years in the making, Hammons’s tribute takes the form of the silhouetted shape of the very structure that stood on Pier 52 off of the Gansevoort Peninusla, in which Matta-Clark made his indelible (though fleeting) mark.

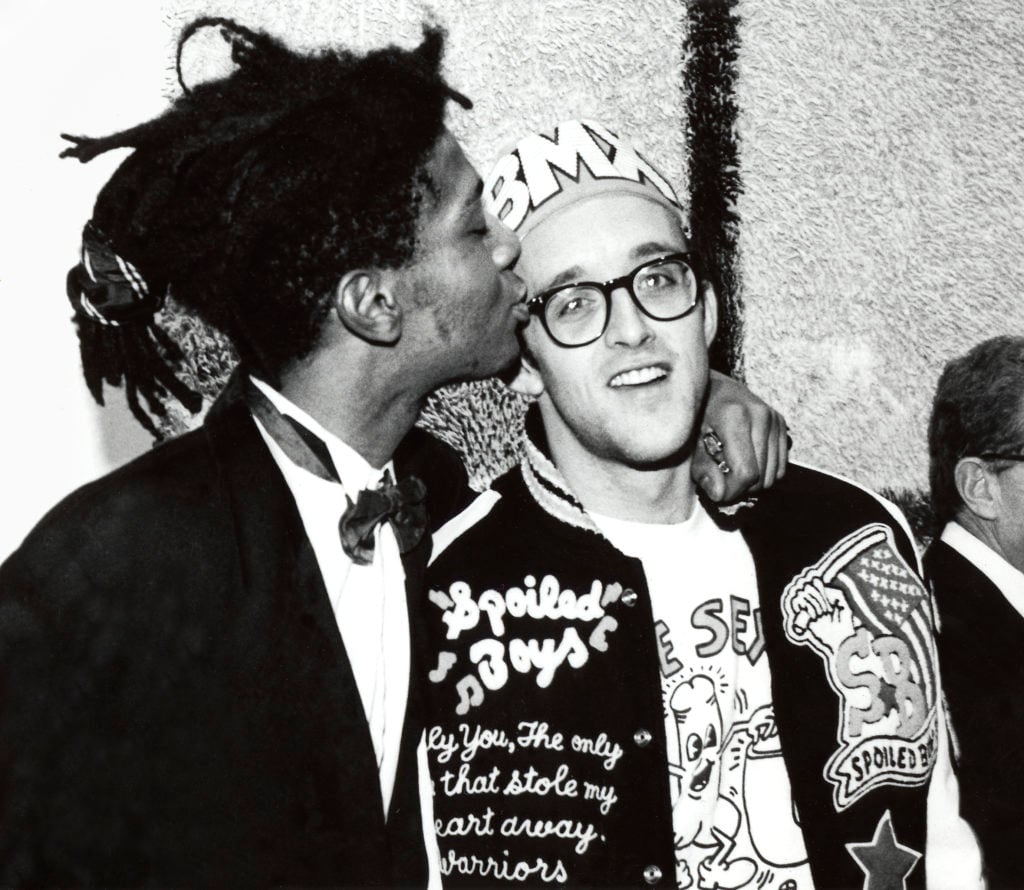

George Hirose, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring at the opening of Julian Schnabel, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1987, © George Hirose, 1987.

If you had to pinpoint the moment when the many rigorous “-isms” of mid-century American art ceded the floor to the burgeoning underground that would define the 1980s and ‘90s, it would be the 1981 “New York/New Wave” exhibition at MoMA PS1. A celebration of the cross-populated downtown music and art scenes, the Diego Cortez-organized show boasted an incredible lineup, including Andy Warhol and Lawrence Weiner. But today it’s remembered as the coming out party for two younger talents: Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring.

Visitors pass in front of a painting by Jean-Michel Basquiat entitled Boy and Dog in a Johnnypump. Photo: Fabrice Coffrini/AFP/Getty Images.

With that show and their rapid ascent to fame in the years that followed, the two artists helped usher graffiti art into both the hallowed halls of institutional art and mainstream pop culture—and the gap between “high” and “low” art has only shrunken since. But it was more than just spray paint that these and other artists associated with the moment helped legitimize. It was also the host of identities and interests they brought with them—a sense of sexual liberation and defiant queerness, as well as an embrace of hip-hop culture. The more time that has passed, the more revolutionary “New York/New Wave” seems.

Some of Nan Goldin’s best work, including The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, was created in the 1980s—and she too was among the artists in “New York/New Wave.” But by the time the photographer became the subject of a mid-career survey at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1996, she was not positioned as another product of the anything-goes energy of the previous decade. She was, suddenly, a prophet of its aftermath, when the drugs had worn off and a deadly health crisis had turned a spirit of liberation into an omnipresent fear.

Nan Goldin, Self-Portrait on the train, Germany (1992). © Nan Goldin. Courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Art had become soberingly political by the mid-90s, and Goldin’s work fit right in. But beyond its subject matter, the Whitney’s “I’ll Be Your Mirror” exhibition also heralded the arrival of a new type of candid, lo-fi photography that would go on to be tremendously influential—particularly in the years when cameras went from being an optional accessory to an everyday tool in our pockets at all time. Goldin’s legacy didn’t start with the Whitney show, and it certainly didn’t end there either, but you can’t tell the story of her career—or the story of contemporary photography—without it.

Artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude walk with New York City Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg before unfurling the first gate in the “The Gates, Central Park, New York, 1979-2005.” Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images.

It’s simply unacceptable to create a list of “defining New York Art Moments” and not include The Gates, Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s iconic 2005 artwork. All the ingredients were in the pot: great artists, great ambition, great New York landmark. After decades of planning, the famed duo installed 7,503 vinyl gates along 23 miles of walkway in Central Park. Hanging from each structure was a panel of saffron-colored fabric that danced in the winter wind—a poetic detail that elevated their homage to Japanese torii gates and put the project in conversation with the artists’ previous efforts.

Interior of Christo and Jeanne-Claude, published by TASCHEN.

For all its artistic achievements, The Gates was also a major feat of civic planning—one that required a team of engineers and hundreds of other dedicated workers, plus multiple manufacturers across two countries. The installation was only on view for just over two weeks, even though Christo and Jeanne-Claude had begun work on it a full 26 years prior. Even more impressive was the financing of it all: as with all their major installations, the partners in life and work funded The Gates entirely by themselves, without contributions from sponsors or donors. Those lucky enough to have experienced the artwork live often talk about it in the once-in-a-lifetime way people talk about a total solar eclipse: one of those rare collective phenomena made all the more magical for its ephemerality.

You could populate much of this list with projects by the seminal public art outfit Creative Time, but for all its highlights, the organization’s 2014 exhibition with Kara Walker might be its greatest achievement. It’s probably Walker’s too, even if—or perhaps because—it represented a dramatic departure from the modestly-scaled work for which she was best known.

People view Kara Walker’s “A Subtlety,” a seventy-five-and-a-half-foot-long and thirty-five-and-a-half foot-tall sphinx made in part of bleached sugar at the former Domino Sugar Refinery on May 10, 2014, in Williamsburg. Photo by Andrew Burton/Getty Images.

A Subtlety (2014) did not lack for ambition, despite its name. It’s official subtitle was more to the point, and doubled as a declaration of intent: A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant. Walker used some 80 tons of sugar to erect the installation’s towering centerpiece, a 35-foot-tall sculpture of a sphinx-like woman that made for a haunting anti-monument to the conflicted history of the trans-Atlantic sugar trade—and a reminder of its legacy today. In the years since its debut, A Subtlety has become one of the most enduring images of 21st century art—and rightly so. It is a masterful synthesis of material and idea, both simple and mysterious. Even in memory, you feel it in the gut.

But the show’s impact went beyond its walls, too. Installed in a soon-to-be-demolished sugar plant on the edge of New York’s then- trendiest neighborhood, Walker’s work kickstarted conversations about class, labor, and the ways in which art is used to perpetuate problematic cycles of urban renewal. Almost as quickly as it opened, A Subtlety became required viewing for New Yorkers and others implicated in its discourse. The fact that lines stretched out the exhibition’s door for the entirety of its eight-week run just underlined the relevancy of one of Walker’s central prompts: who are public artworks like this for, really?